The dinosaurs were snuffed out in a geological instant (well not exactly, but that is a popular image). The Chicxulub bolide, its girth 10-15 kilometres, collided with Earth 65 million years ago, leaving a 150 kilometre-wide crater and enough dust and aerosols in the upper atmosphere to darken latest Cretaceous skies for decades.

Like all planetary bodies in our Solar System, Earth has received its share of meteorite and comet impacts. We still bear the scars of some. Every day, bits of space dust and rock plummet towards us – most burn up on entering the atmosphere, but a few make it to the surface. Occasionally they even startle us with air-bursts – Tunguska in 1908, Chelyabinsk (2013), both in Russia. But humanity has never witnessed a decent sized impact, at least in recorded history. It’s all theoretical.

On March 24 1993 astronomers David Levy, and Carolyn and Eugene Shoemaker discovered what was to become known as comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 (it was the 9th comet with an orbital period less than 200 years to be discovered by the trio). The comet was unusual because it seemed very long for its over all size and brightness (a brightness much less than could be seen with the naked eye). Observations from other telescopes confirmed there were in fact multiple nucleii, strung out like train carriages. Further studies also suggested that the comet had been captured by Jupiter’s gravity, and was orbiting that planet rather than the sun. It was surmised that the comet had been fragmented during a close-approach to Jupiter, broken apart by a gravitational tug-of-war. Shoemaker-Levy 9’s orbit was also decaying, with the likelihood of impact a real possibility (by October 1993 the probability was estimated at 99%). The Shoemaker’s and Levy’s discovery was fortuitous to say the least.

By mid-July 1994, the world’s telescopic eyes and satellite sensors were turned toward Jupiter; here was an opportunity to witness an extraordinary astronomical event – the first direct observations of major celestial body impacts. At least 20 large pieces of the comet were headed for Jupiter. The trajectory of the comet train was such that the comet fragments would occur a few minutes beyond Jupiter’s horizon, out of direct sight from Earth. But again, in another stoke of luck, the spacecraft Galileo was able to turn its sensors directly to the impact sites. The Hubble’s telescope was also focused on Jupiter’s horizon, because the impact sites would come into view minutes after Shoemaker-Levy 9 had made contact (Jupiter’s day is a little less than 10 hours, almost 2.5 times shorter than Earth). Two additional spacecraft, Ulysses and Voyager 2, also observed the proceedings.

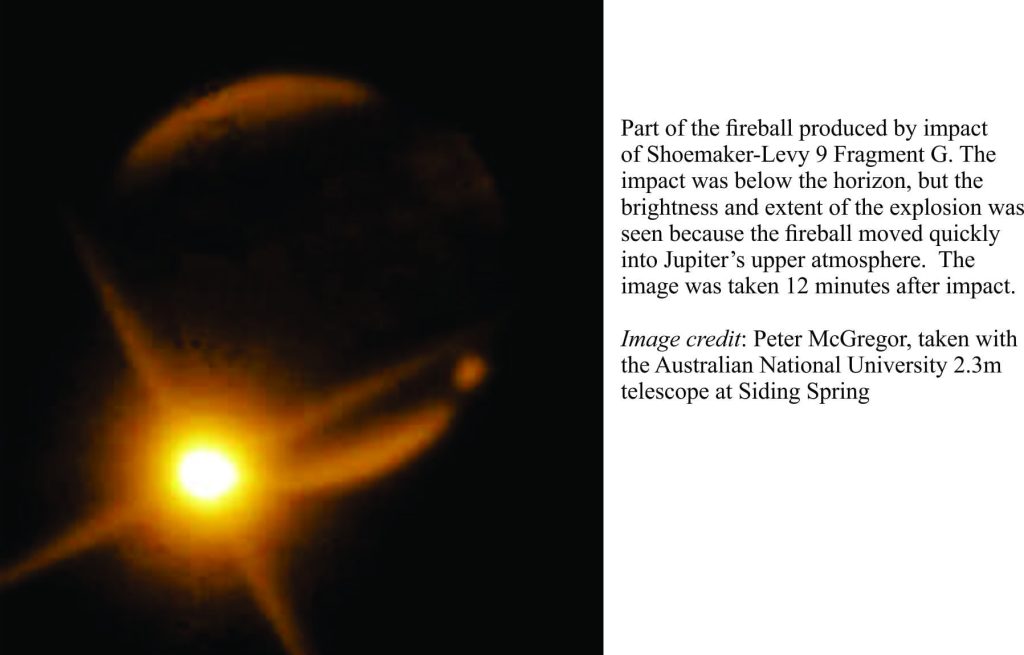

Twenty identified comet fragments collided with Jupiter, one after the other, from 16th to 22nd July 1994. The largest fragment was a sizeable two kilometres diameter, having approach speeds 60 Km/second, or 216,000 Km/hour. All that momentum was about to be converted to heat, pressure waves, and ejecta at the moment of impact. Unlike the rocky planets and moons, there were no tell-tail craters. Instead, collision with the Jovian atmosphere (mostly hydrogen and helium, and clouds of ammonia, sulphides and water) produced massive fireballs that soared rapidly to 3000 km. The fireballs, visible for up to 80 seconds had initial temperatures of 23,700°C (42,700 °F), that cooled to about 1,200°C (2,240 °F) as the gas ‘bubble’ expanded. The extreme temperature contrast between the Jovian cloud-top (−143 °C; −226 °F) and the fireball made detection easy by satellite sensors.

Although it did not witness the impacts directly, Space Telescope Hubble did ‘see’ the bright fireball, nicely captured in a time-lapse GIF (processed by the Max Plank Institut) .

The images show a fireball appearing over the bottom left horizon; for a brief time it is brighter than Io moonshine (right). The fainter oval shaped region between Io and the fireball is the Great Red Spot.

As if the fireballs weren’t enough, each impact generated huge acoustic or gravity pressure waves that propagated at speeds of 450m/second (1620 km/hour). The speeds were estimated from time-lapse images at individual impact sites.

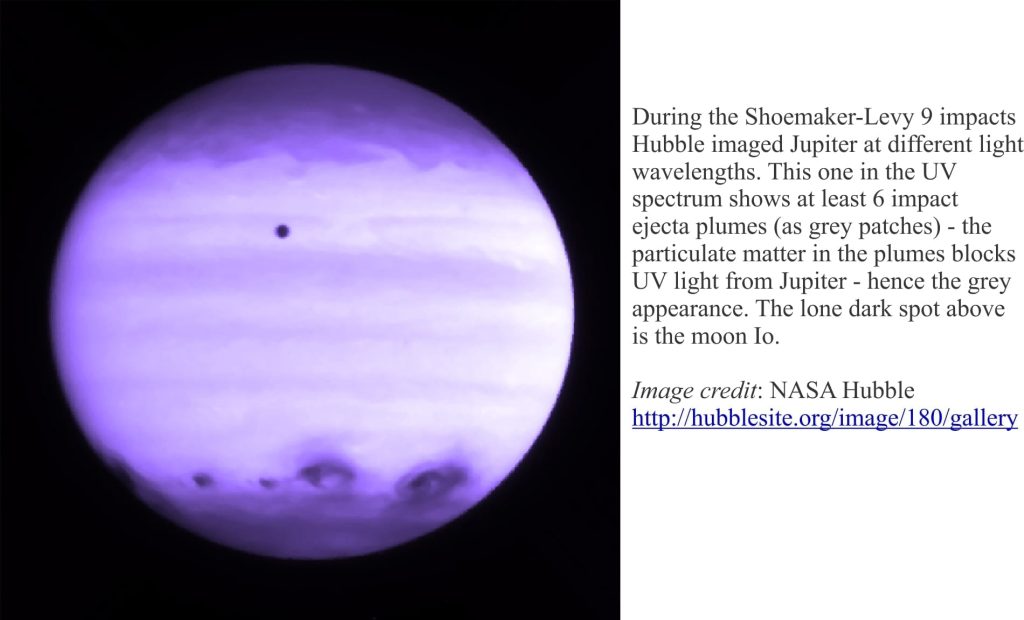

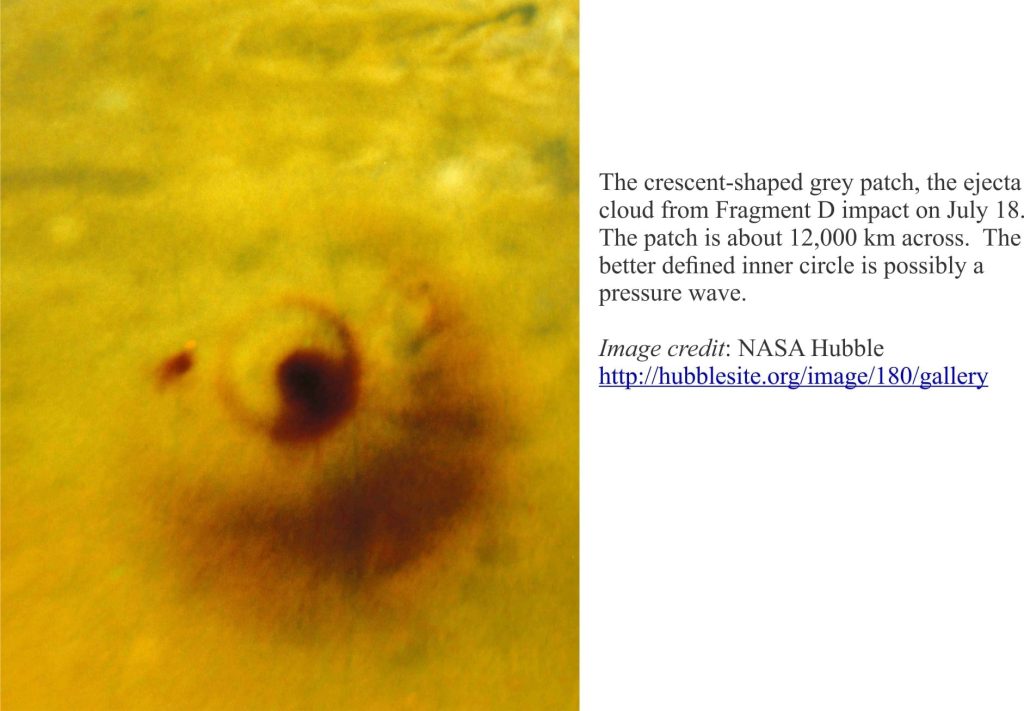

Instead of craters, the impacts left a string of greyish, circular to crescent-shaped splodges. The grey patches are clouds of dust and aerosols ejected into the Jovian stratosphere.

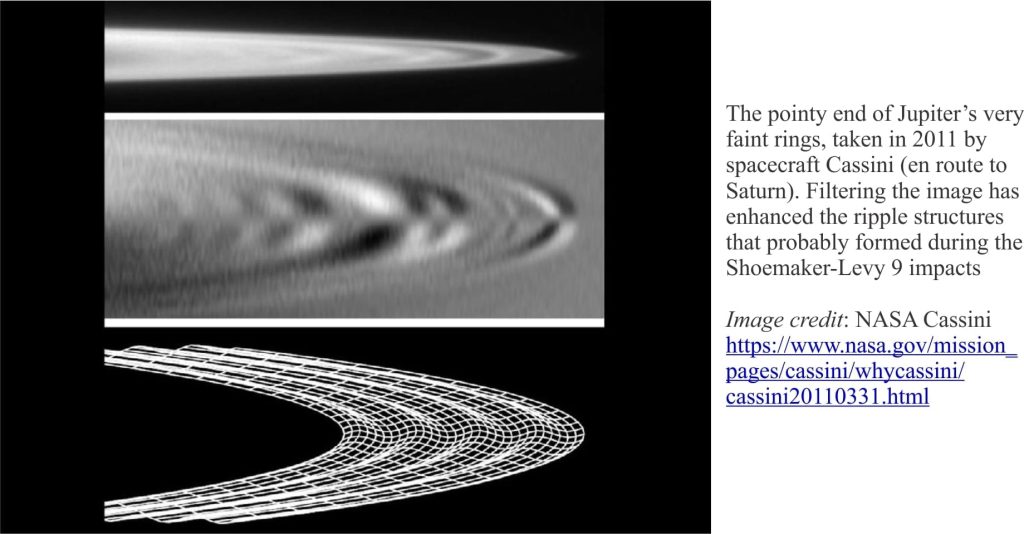

The patch shown in the Hubble overhead view below is 12,000 Km across – equivalent to the diameter of Earth. Most patches had merged with Jupiter’s cloud-tops a few months after impact, dispersed by the never-ending storms. However, it was discovered in 2011, during a pass by spacecraft Cassini, that Jupiter’s rings (yes it has very faint Saturn-like rings) showed unusual rippling effects; ripples that could be traced back to the Shoemaker-Levy 9 impacts. Even though the ejecta clouds had dispersed quickly, there seems to be longer-term disruption to normal Jovian life.

Today Jupiter looks much like it did before Shoemaker-Levy 9; a roiling mass of atmospheric storms. But the impacts are a sober reminder of our own vulnerability – being impacted by one 2km fragment would be bad enough, but a whole string of them…! Shoemaker-Levy 9 has given us a unique, if disquieting analogy into the blast effects from a sizeable bolide – the fireball, destructive surface pressure and deeper seismic waves (because Earth is rocky), and ejecta clouds that could darken our skies for decades, even centuries.

The scientific fallout from this event is still being felt; the political fallout resulted in NASA (and other organizations since then) being tasked to identify near-earth objects – it is generally considered that some warning of impending impact by extraterrestrial flotsam measuring in the 10s to 100s of metres, would be nice. Witness the storm of a different kind, generated by media prophesying our doom from recently discovered asteroid Bennu, that has an orbit bringing it quite close to Earth –about 200 years hence.

The Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker and David Levy legacy lies in their service for science, and for society at large. Eugene Shoemaker passed away in 1997. His ashes were placed in a small capsule aboard the spacecraft Lunar Prospector, that in 1999 crashed (deliberately) onto the lunar surface. A fitting memorial.