I always feel a sense of unease when hearing of natural disasters. I live in a country where earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, landslides, floods and the threat of tsunamis all occur within a relatively small land area. In Canada, I lived on a small island (a daily ferry commute), nestled in a typical West coast fiord near Vancouver and more than once I pondered the possibility, even inevitability of those towering rock walls suddenly obeying the laws of gravity.

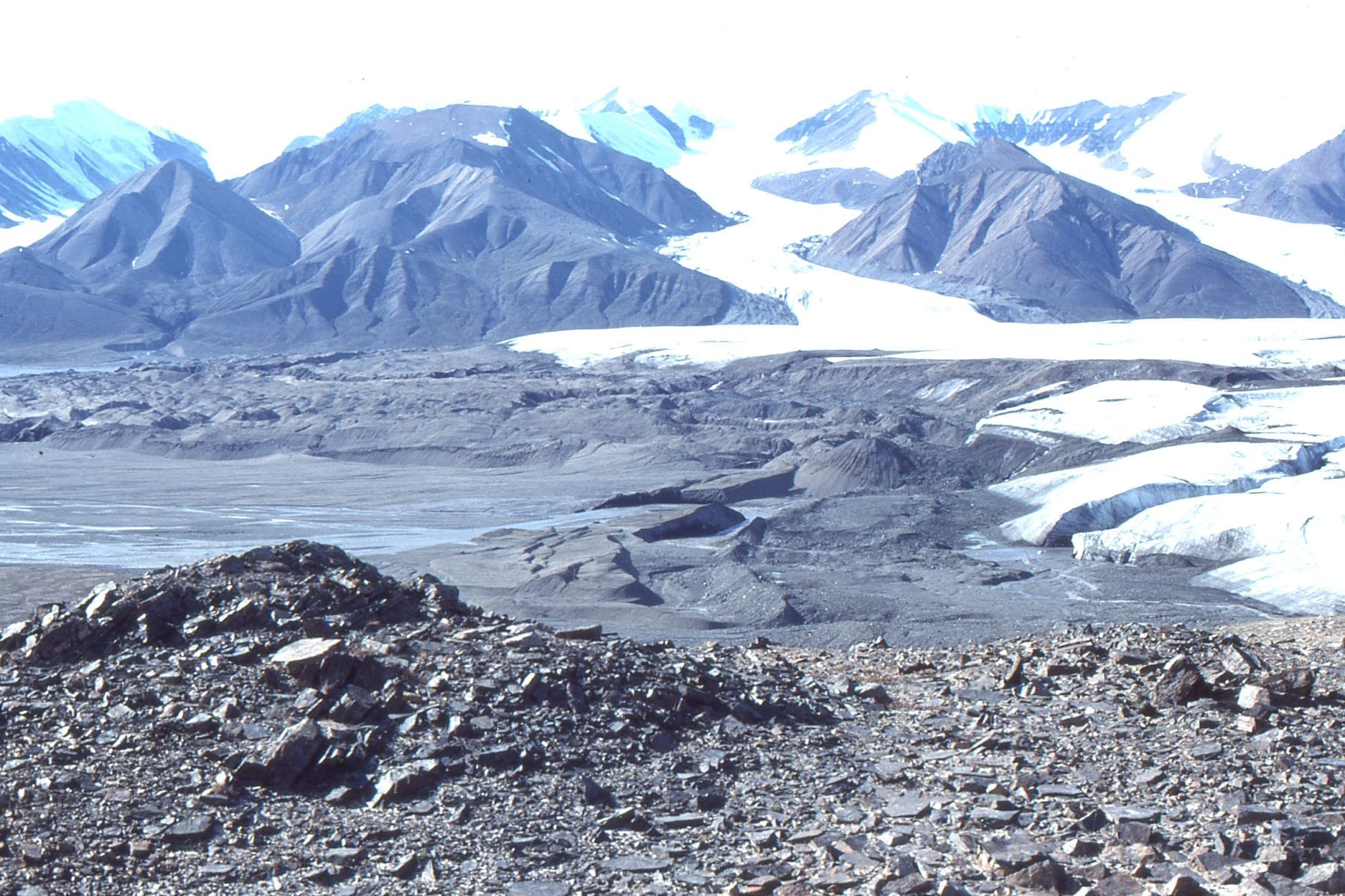

Fiords exist because of ponderous gouging and plucking of the solid earth by rivers of ice; testaments to ancient glacial climates and the forces of nature. Fiord landscapes are stunning, beautiful in and of themselves and, I suspect because they invoke a sense of awe. But this is a façade. Rock walls, almost vertical in places and towering 100s if not 1000s of metres are inherently unstable; any glaciers at the head of the fiord or hanging off the valley walls exacerbate the problems. Landslides, rockfalls and glacier calving inevitably end up in the sea and the resulting tsunamis can be terrifying. The video here shows these guys had a lucky escape after venturing a bit too close to a calving, Greenland glacier.

All that energy focused through a narrow gap

Terrestrial or submarine landslides that occur on open coasts can produce locally massive tsunami waves (10s of metres high) but these tend to dissipate radially. There are well known examples on oceanic volcanoes like Canary Islands and Hawaii. From the North Sea, the Storegga submarine landslide about 8000 years ago must have devastated parts of Britain and northern Europe coasts with wave run-up locally 20m and more. The Youtube Video here shows a recreation of this event.

Tsunamis generated in fiords react differently because the wave energy is focused, generally along the length of the fiord. Some of the largest waves on record, either observed directly or the immediate aftermath, have been generated in fiords. There are many examples – historical and prehistoric. The three I have chosen are well documented and pretty spectacular. They provide a sober reminder of what can happen when nature casually flicks a finger at us.

Talfjord, Norway, 1934

On April 7, about 2 million cubic metres of rock fell about 700m into the fiord. Displacement of water instantly created a wave that initially was 62m high near the landslide impact. By the time the wave had reached the village of Talfjord some 5 km away it was still 16m. It was about 3am and most in the town were asleep. Geological mapping has shown that there have been at least 10 landslides along a 7km stretch of the fiord, and along the adjacent Storfjorden 108 rockslides have been identified, all occurring since deglaciation about 14,500 years ago (Source: Harbitz et al. 2014, Coastal Engineering, v 88). It was common knowledge at the time that the rock mass above the fiord was unstable, where tension cracks were forming. Unfortunately, there are no real geotechnical solutions to a problem like this, other than monitoring.

A similarly unstable, but much larger rock mass in Storfjorden (about 50 million m3) has been monitored for several years. Signs of instability include tension gashes that seem to become larger every year. Early warning systems are in place although the warning time for the closest villages is likely to be no more than a few minutes. Fingers are crossed.

Paatuut, Greenland, November 21, 2000

A large landslide at Paatuut located in a fiord on Greenland’s west coast, moved about 90 million m3 of rocky debris about a third of which splashed into the fiord. The landslide was initiated 1000-1400m above sea level. No one witnessed the landslide but the resulting tsunami was recorded in a small village about 40km away. On the side of the fiord opposite Paatuut an abandoned mining town (Qullissat) about 25km away was almost destroyed. Wave run-up at Qullissat was 28m (observed in the lines of debris) and it is estimated that the wave near the landslide itself had a run-up of about 50m. Seven kilometres northwest of Paatuut several icebergs were left stranded up to 700m from the coast on an alluvial fan. Fishing crates and other flotsam were stranded to 800m inland and 40m above sea level.

Lituya Bay, Alaska, July 9, 1958

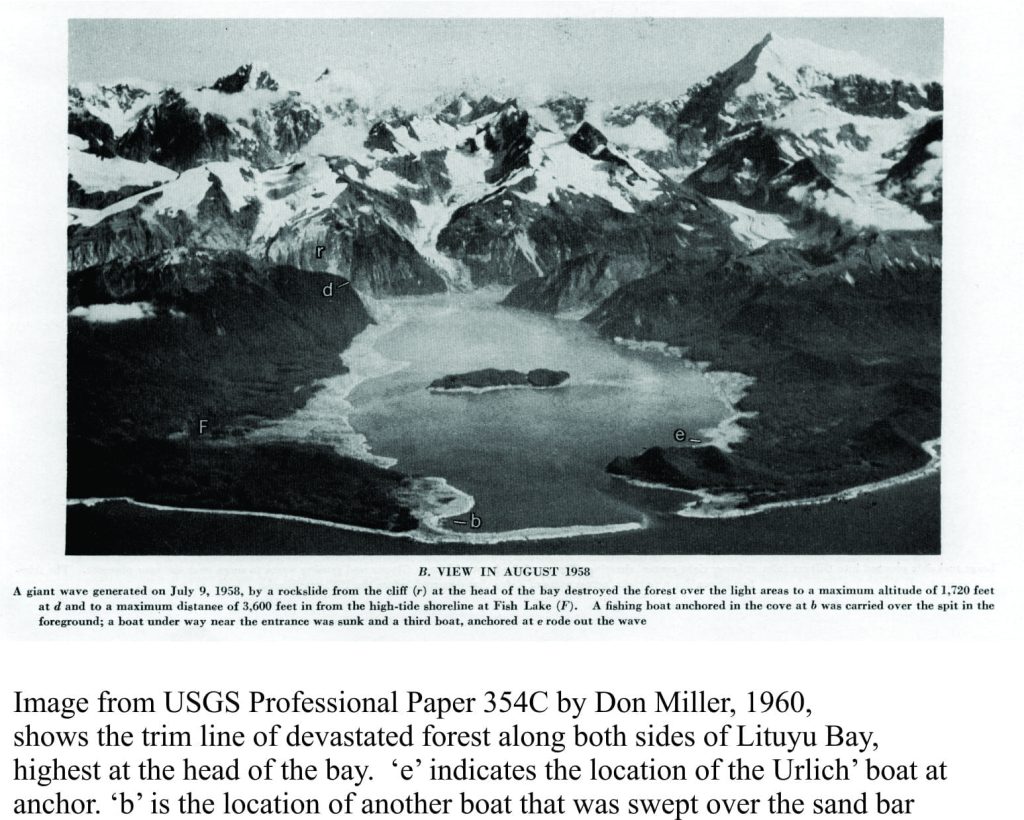

One of the largest waves ever observed (and survived) took place in Lituya Bay, Alaska during a 1958 magnitude 7.8 earthquake along the Fairweather Fault (Fairweather Fault is part of an extensive system of active faults that mark the boundary between the Pacific and North American plates – it is a fundamental structure in the Alaskan Panhandle.).

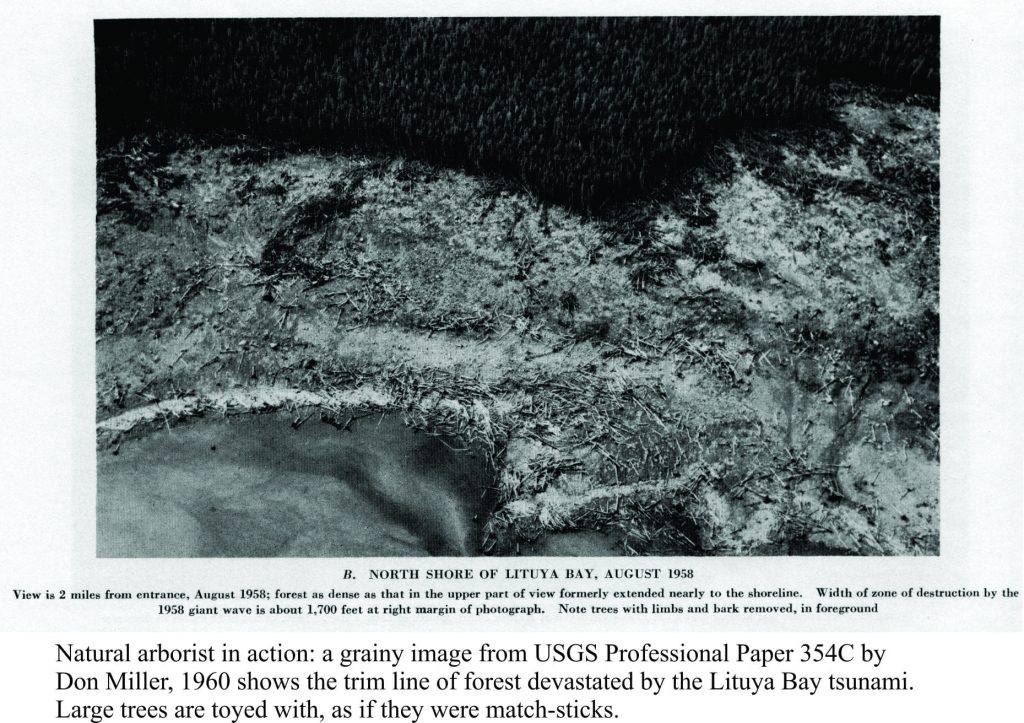

The tsunami was triggered by a 30 million m3 rock mass falling more than 900m into Gilbert Inlet at the head of Lituya Bay. It seems likely that collapse of the glacier front at the head of the Bay also played a role in generating massive waves. The wave nearest the landslide had an incredible 524m run-up (1720 feet), but subsided to about 10m near the entrance to the open sea. Wave run-up was easily mapped along Lituya Bay by the line of devastated forest; also known as trim lines.

Howard Urlich and his 7 year-old son, from their fishing boat anchored in a sheltered bay, provided first-hand accounts of what must have been a terrifying experience. They awoke to a wall of water, that from their estimates was 50-75 feet high (15-22m) coming at them. The boat was anchored in about 10m of water. Unable to release the anchor Urlich let the anchor chain run free – it snapped at about 40 fathoms (73m – note however that the boat would have been carried forward at this point in their adventure and the 73m does not indicate true wave height; but it does give some indication). The boat was carried along the front of the wave over the adjacent shore and several metres above the trees. It was then washed back into the bay, still upright. A couple of other boats in the bay didn’t fare so well. The Youtube video shows a dramatic reconstruction of events.

Read the first USGS account by Don Miller, 1960 here, and some old images here.

The list of terrifyingly spectacular fiord tsunamis goes on. For example, a more recent event at Taan Fiord Alaska, October 17, 2015 – as if Lituya Bay wasn’t enough; this one is still under investigation, but it looks like the wave was capable of hedge-trimming activities to about 150m and tossing boulders even higher.

Postscript

The day I wrote this post ended with a magnitude 7.5 jolt in northeast South Island, New Zealand (north of Christchurch). We live about 800 km north of the Kaikoura epicentre and our house shook and swayed, trees swayed, and water in the pool sloshed over the sides. No damage to us, but considerable building and infrastructure damage farther south. Some aftershocks have been greater than magnitude 6. A rude awakening…