A post in the How to… series on carbonate mineralogy – limestone classification

The classification of carbonate rocks, like that of sandstones, has gone through a few iterations. Two schemes have stood the test of trial and error, in the field and through microscopes; both were compiled in the late 1950s – early 60s, each serves a slightly different purpose, both are still popular. They are the classification schemes of R. Folk (1959, 1962), and R. Dunham (1962). These two schemes form the backbone of modern carbonate classification and are summarized here, but keep in mind that quite a few iterations have been published.

Folk’s classification scheme

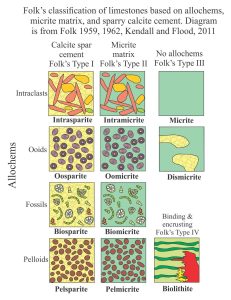

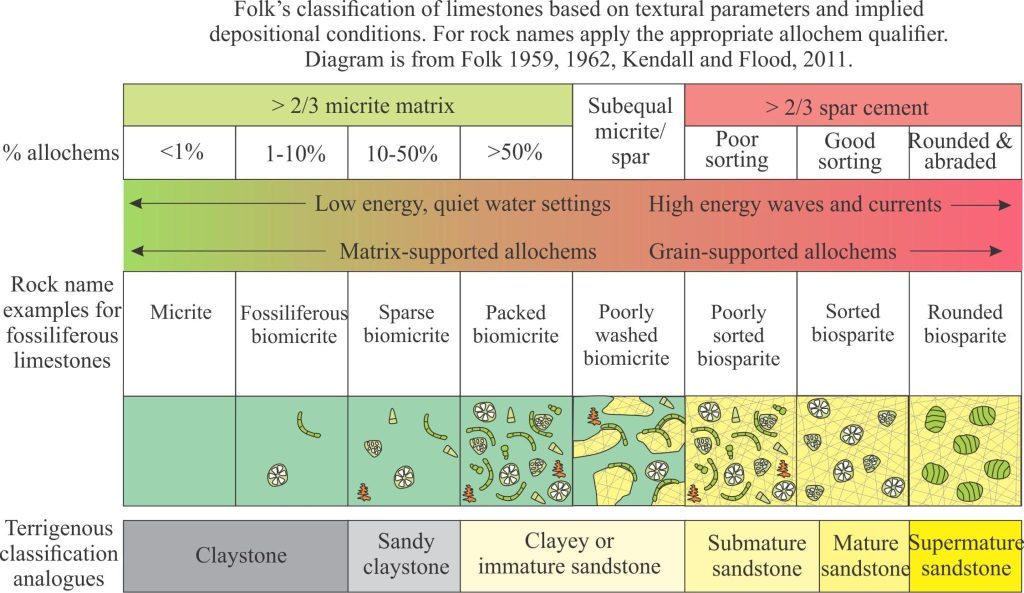

Folk’s scheme for carbonates is in some respects like the one he devised for terrigenous sandstones. It is based on the proportions of matrix, in this case lime mud, and framework components that are mostly allochems (grains that have been subjected to some degree of transport). At one end if the spectrum there is pure mud, or micrite; at the other end clast-supported frameworks with no mud. The spectrum of textures also reflects the energy of the depositional system. The pore volumes in clast-supported limestones are filled with cements, commonly sparry calcite mosaics, some with micritic cements. The degree of grain sorting in these sparites also increases. Grain size follows a relatively simple size-class like the Wentworth scale:

- Lutites, 0.004 – 0.062 mm, that are approximately equivalent to mud (silt and clay)

- Arenites, 0.062 – 1.00 mm (very fine- to coarse-grained sand)

- Rudites, 1.00 mm to boulder range

Folk’s limestones are classified as either micrites or sparites with qualifiers added for the kinds of allochems (ooids, pelloids, fossils and intraclasts) and grain size. Identification of the allochems usually requires a microscope. Hence, Folk’s scheme is best applied to thin sections.

Folk extended this basic classification to include the percentages of micrite and spar cement (diagram below). The cut-off percentage between pure micrite and a micrite with allochems is 1%, 1-10% skeletal fragments is a fossiliferous micrite, 10-50% a sparse biomocrite, and >50% a packed biomicrite. Other qualifiers like pelloids and ooids use the same designations. Thus, an oosparite may be an unsorted oosparite, or if matrix-supported a sparse oomicrite.

Rigid structures like reefs and bioherms were placed in a category of their own – biolithite. The category dismicrite refers to micrite that has been disturbed by burrowing or erosion where voids have been filled by sparry calcite (i.e. disturbed micrite). However, it may be difficult to distinguish between a dismicrite and a micrite that has undergone partial recrystallization to calcite spar.

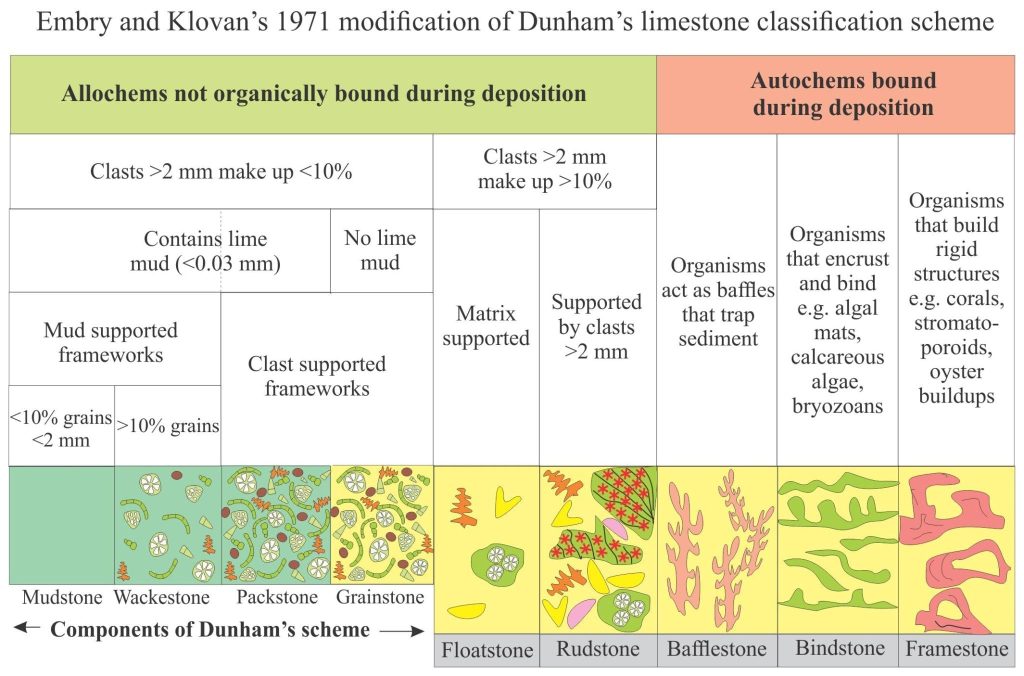

Dunham’s classification scheme

This scheme is more applicable to outcrop, hand specimen and drill core. It too is based on textural attributes but only those acquired during deposition (which means cements are excluded). His scheme uses three basic components:

- The proportion of mud that differentiates between muddy limestones and grainstones (the latter having no mud),

- The percentage of grains giving us a mudstone, wackestone or packstone, and

- The presence of binding agents (mostly biological) giving us a boundstone.

Both Folk and Dunham apply a separate catch-all category of biolithite and boundstone respectively, for limestones containing fossils and inorganic structures bound by algal mats and more rigid frameworks like corals, stromatoporids and bryozoans. One could apply a qualifier, such as stromatoporoid boundstone, but this gives little paleoenvironmental information on the kinds of structures involved. While working on some Devonian reefs in the Canadian Arctic, Embry and Klovan realized that additional classification categories were required to fully describe the limestone structures they encountered. Their classification became an expansion of Dunham’s scheme, the basics of which have also stood the test of time, albeit with the odd modification.

Embry and Klovan added three new categories:

- Bafflestone where organisms trap sediment. By their own admission, Embry and Klovan note that identification of organisms responsible for trapping is equivocal.

- Boundstone where material is bound by encrusting and binding organisms, such as calcareous algae and cyanobacterial mats, and

- Framestone that is constructed by framework-building organisms like corals and stromatoporids.

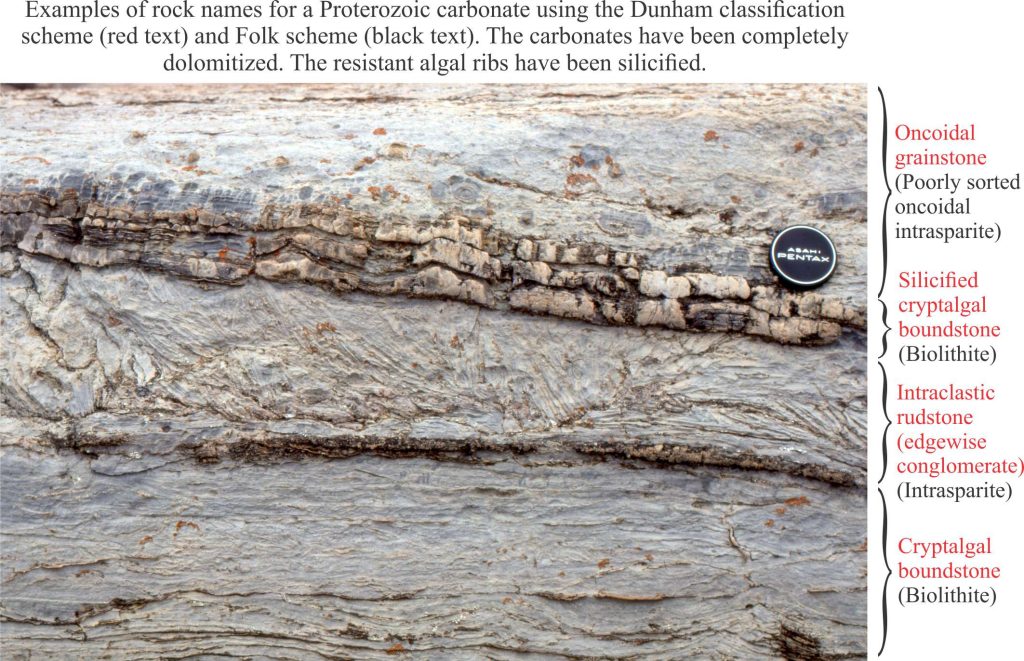

So which scheme does one use? The popularity of either scheme depends on which text or journal paper you read – some say Dunham’s scheme, others Folk’s scheme. It is also the case that the two are used interchangeably. If your study focuses on field and outcrop, then Dunham is the logical choice; if the focus is petrographic and thin section then Folk. And if you incorporate outcrop and microscope work, then perhaps use both schemes with cross-referenced rock names. To some extent it depends on personal preference.

Carbonate students should also look at an evaluation of these two popular schemes by Stephen Lokier and Mariam Junaibi. (2016). This paper (open access) looks at some of the modifications to both Folk and Dunham schemes. They find Dunham’s scheme (or modifications thereof) is the most popular. Their own modified scheme is shown below; note that Bafflestone is no longer used here.

*From Sedimentology, v 63, p. 1843-1885, Figure 12 – see link above)

Other post in this series:

Mineralogy of carbonates; skeletal grains

Mineralogy of carbonates; non-skeletal grains

Mineralogy of carbonates; lime mud

Mineralogy of carbonates; carbonate factories

Mineralogy of carbonates; basic geochemistry

Mineralogy of carbonates: Stromatolite reefs

Important literature contributions

R.J. Dunham, 1962. Classification of carbonate rocks according to depositional texture. In W.E. Ham (editor), Classification of carbonate rocks. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoir 1, p. 108-121.

A.F. III. Embry and J.E.Klovan, 1971. A Late Devonian reef tract on northeastern Banks Island, N.W.T. Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum geology, v.19, p. 730-781.

R.L. Folk, 1959. Practical petrographic classification of limestones. Bulletin American Association of Petroleum Geologists, v. 43, p. 1-38.

R.L. Folk, 1962. Spectral subdivision of limestone types. In W.E. Ham (editor), Classification of carbonate rocks. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoir 1, p. 62-84.

C.St.J.C. Kendall and P. Flood, 2011. Classification of carbonates. In D. Hopley (editor) Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs; Structure, Form and Process. Springer, p. 193-198.