We have installed a new kitchen bench. The company that imports and installs this kind of thing refers to the stone as ‘Granite’, a term that is used for pretty well anything that is igneous, crystalline and not marble.

It is beautiful stone, from India according to our installer and from what I can see via an internet search is probably from the Andrha Pradesh province located on the central to southeast coast. This is a province where stone quarrying is common. From a geological perspective it contains large swaths of (very old) Precambrian ‘granite’, metamorphic and sedimentary rock; it is well known for its mineral wealth and production, including gems and precious metals.

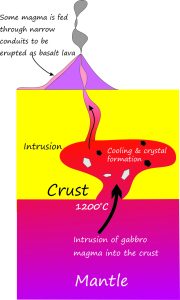

Granite and all its cousins belong to the general class of ‘Igneous’ rock. They originate deep in the earth’s crust and mantle as (molten) magma, and unlike volcanic lava (extrusive) they do not reach the surface; this kind of igneous rock is referred to as intrusive. Crystals form as the magma cools and hardens slowly. The kind of crystals depends on the chemical composition of the magma; if there is a lot of silica, then quartz is a common mineral component (quartz and feldspar are the most common mineral components in true granites). We refer to these kinds of rocks as felsic. Rocks that have little or no quartz crystals are referred to as basic – the rock in our kitchen is the latter kind.

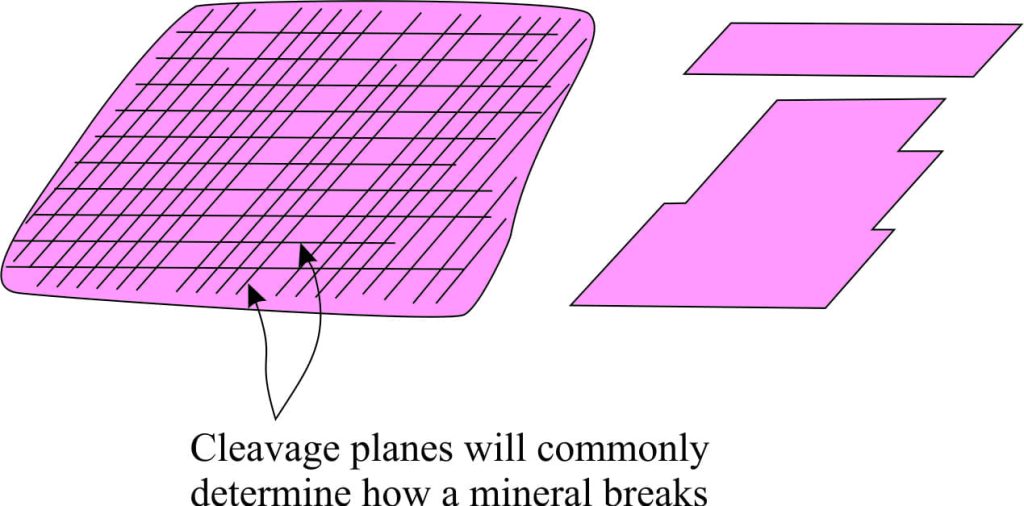

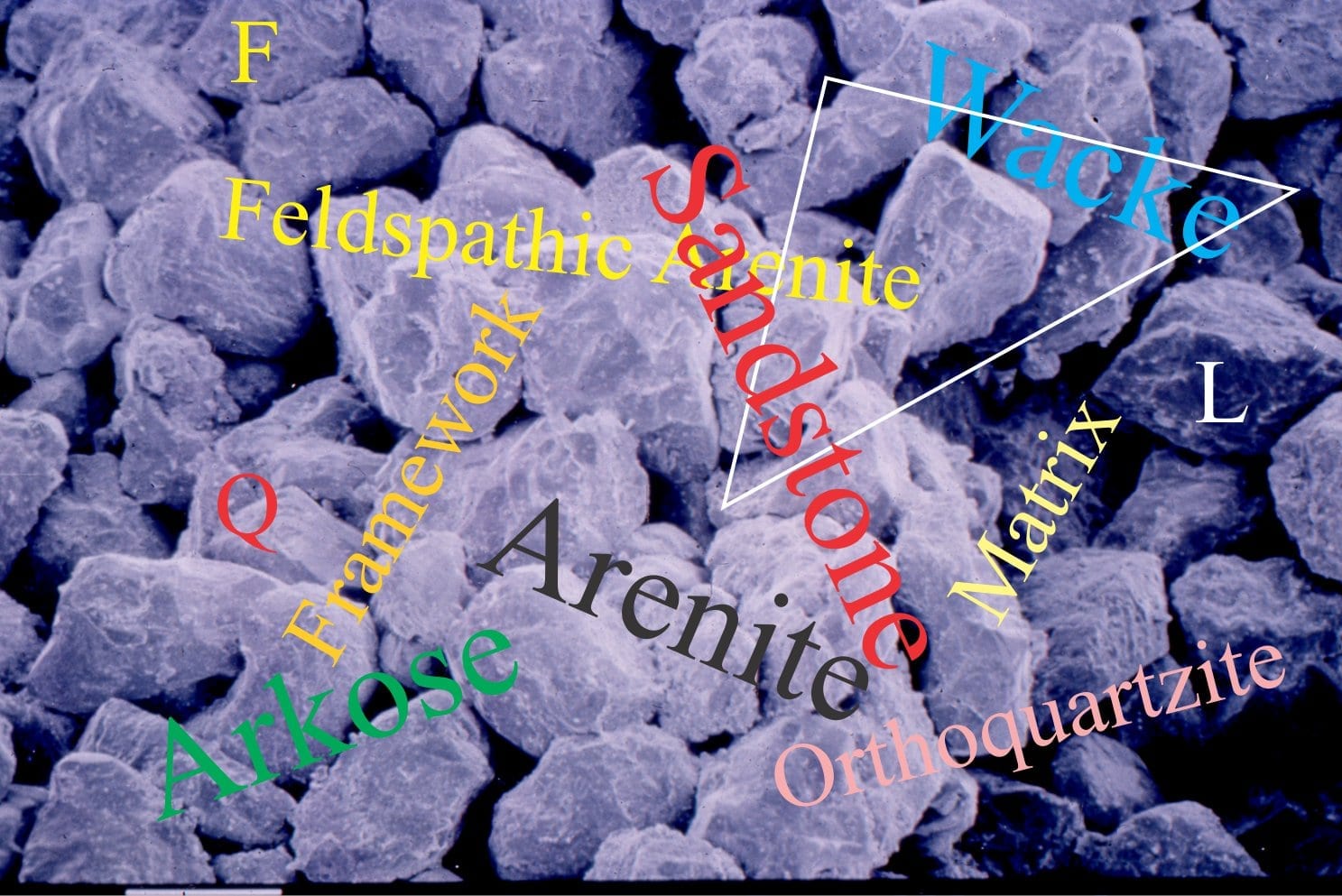

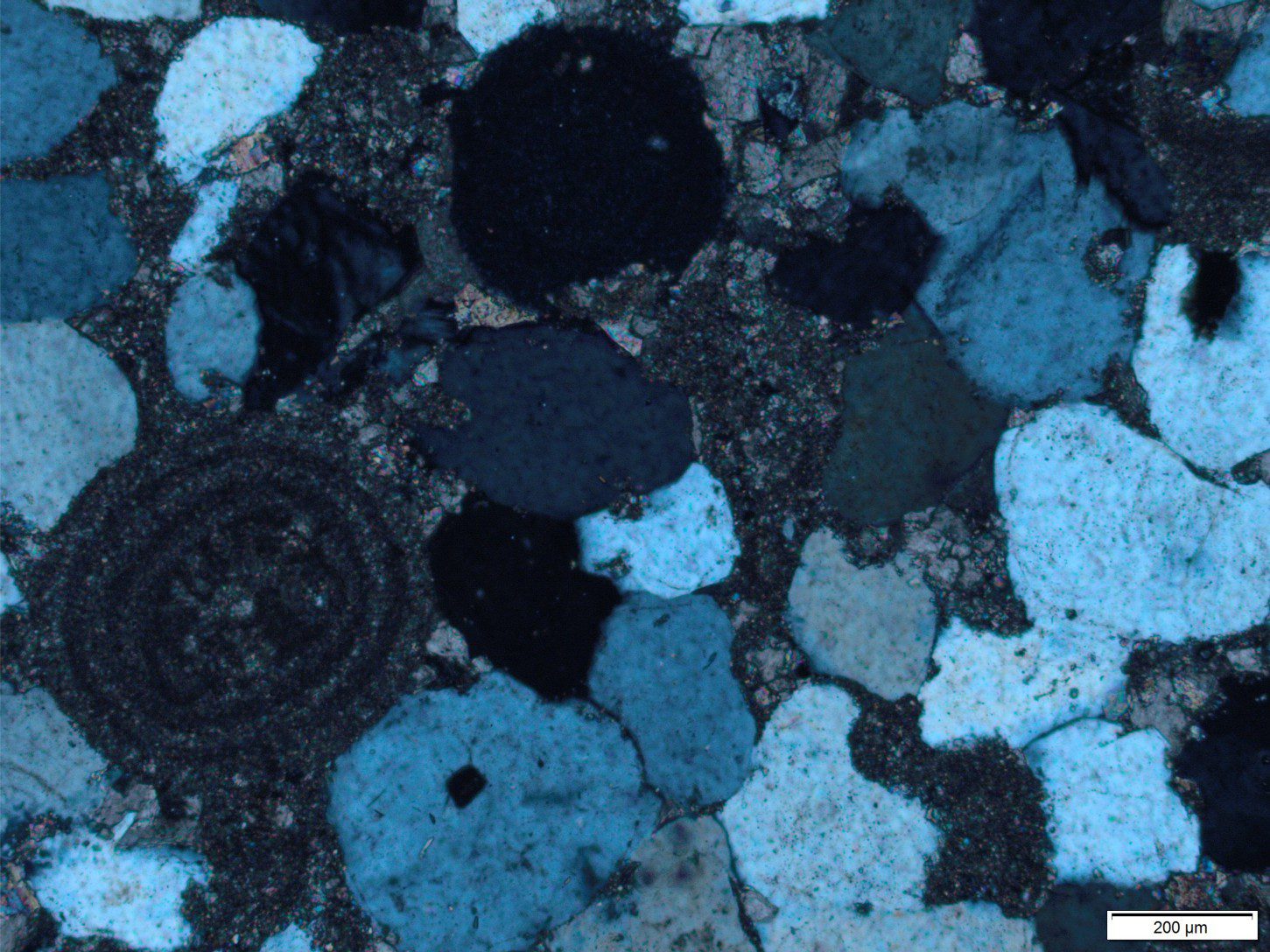

The technical name for our kitchen stone is Gabbro. The temperature of the original magma would have been about 1000oC to 1200oC. It contains mostly feldspar with some crystals 2-4 centimetres long; these larger crystals are called phenocrysts. The feldspar crystals (a type called plagioclase) contain lots of calcium. They also are characterised by very small fractures or ‘cleavage’ that allows crystals to break naturally along smooth, geometric planes. The cleavage pattern can be used (along with other features such as crystal geometry, colour, chemical composition and hardness) to identify the mineral type. Some of the plagioclase crystals on our bench top contain very small (almost black) biotite or pyroxene crystals within their structure; these are called inclusions.

There is a small amount of quartz in our stone (1% to 2%). Quartz has a very poor capacity to cleave – it tends to break a bit like glass. The black minerals include biotite (a dark coloured mica rich in iron) and pyroxene (another common iron and magnesium-rich mineral group found in many different kinds of igneous rock). The crystal sizes are quite large and fairly evenly distributed, which gives the polished surface a beautiful texture.

Gabbro, an intrusive rock is similar in chemical composition to basalt, a rock type that is extruded as lava from volcanoes. Another difference between gabbro and basalt is that the crystals tend to be much smaller in lava because they usually cool much faster (minutes, hours, days) than gabbro (probably several 100s to 1000s of years).

The bench stone is very hard. It will not scratch with common iron utensils; it would scratch with diamond or titanium tools but we haven’t quite gone the distance to acquire these (and don’t really plan to). However, one does need to make sure that really hot plates-pots-pans etc. do not go directly on the stone top or small stress fractures may develop.

I have added an extra utensil to our kitchen collection; a geologist’s magnifying glass (5 times magnification is the most useful). So while I prepare a Ligurian fish stew or my weekend pancake breakfast, I can ponder the mineral and textural kaleidoscope presented by the natural rock; it is quintessentially a geological setting.

3 thoughts on “The Geology of our Kitchen Bench”

Pingback: salomon contagrip

Pingback: Air Max 90 Dam Rea

Thanks. Hope you enjoy the rest of the posts.