Among wine drinkers, the term Terroir can invoke glazed expressions, or in real enthusiasts an opportunity to wax lyrical about the provenance of their beverage. The term is French, morphing from the word terre , the land, or earth. It conveys a ‘sense of place’, the earth, the climate, and the culture of wine-making. In other words, pretty well anything that contributes to a wine’s character.

Among wine drinkers, the term Terroir can invoke glazed expressions, or in real enthusiasts an opportunity to wax lyrical about the provenance of their beverage. The term is French, morphing from the word terre , the land, or earth. It conveys a ‘sense of place’, the earth, the climate, and the culture of wine-making. In other words, pretty well anything that contributes to a wine’s character.

Opinions vary about the real significance of terroir. For some, the cultural foundations are most important in a kind of philosophical, metaphysical way. For others, it is the physical environment in which the grapes grow, are harvested, and finally turned into wine. For the more cynical it is just a marketing ploy, something to make the purchaser and imbiber feel good. The French have honed this to a fine art, to the point where only wine from Burgundy can be called Burgundy, or Champagne from a region and appellation of the same name in north France.

There is still debate about how Terroir is expressed. However, there is no debating the influence that soils, sunshine, summer temperatures, and precipitation have on vine growth and fruit production; some regions are better for red wines, some for white. The real test of Terroir comes in the tasting; can the average quaffer or expert taster tell the difference between growing regions, vineyards within regions, and even separate blocks within vineyards? The answer usually comes down to ‘sometimes they can, sometimes they cannot’. Embedded within all the taste tests, competitions and marketing ploys, is a fair bit of creative thinking, luck, and snobbery. But it is fun. Most of us can enjoy a good tipple without getting too carried away, although after a couple of generous glasses, the ability to wax lyrical certainly improves.

Geology is concerned not just with rocks, but also the formation of soils, the evolution of landscapes, and their relationship with climate. Although geologists don’t usually study climate per se, they are interested in how the vagaries of weather continually wear rocks down, and how the products of erosion and mass-wasting are moved by rivers, glaciers, landslides and the like. This provides us with all the excuses we need to visit vineyards and think about terroir.

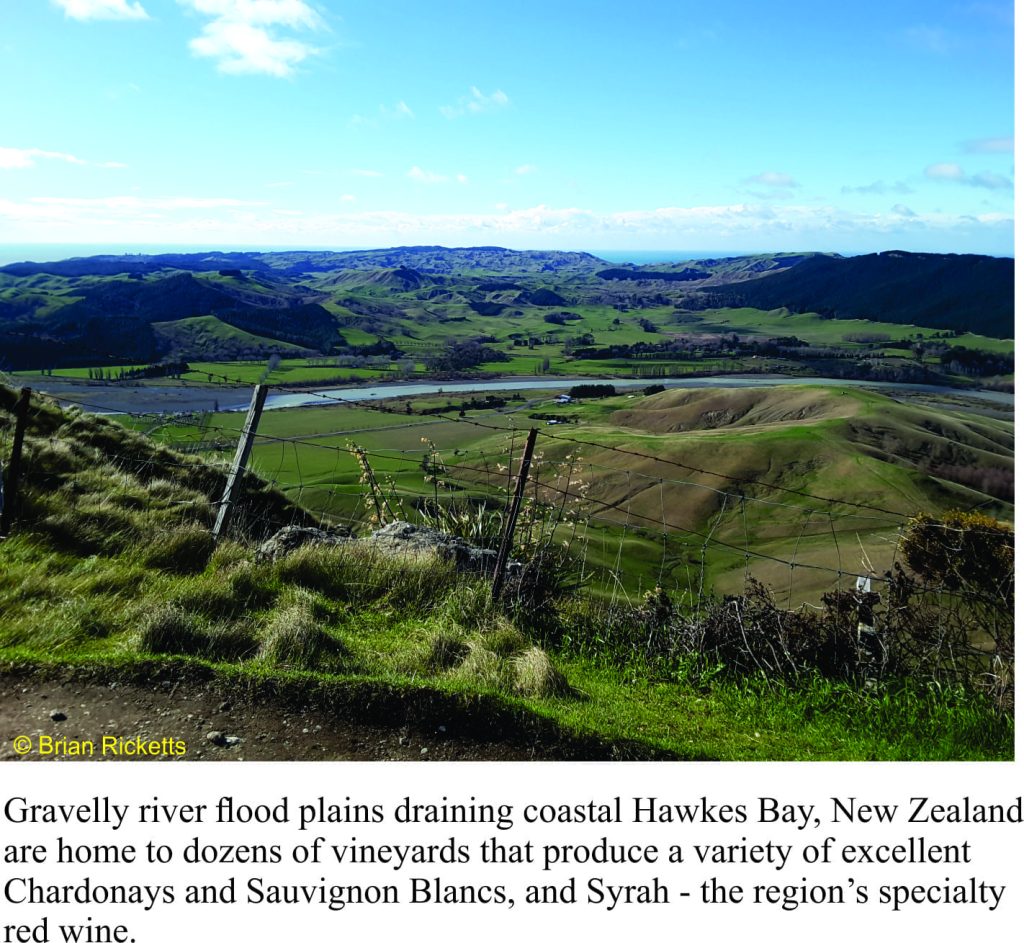

Grape vines need dirt; soils having neutral pH to slight acidic, a decent organic component (topsoil), and it seems, a healthy microbiota, especially beneficial fungi. And like wine-drinkers, grape vines enjoy good drainage, the kind one gets in soils developed on river gravel, sands and sandstone, or volcanic ash. Vines don’t like having wet feet. This is the reason why so many wine regions take advantage of broad flood plains and gently sloping hills. Maximizing sun exposure is good for vine vigour and heating soils. Some French vineyards in Châteauneuf-du-Pape even go as far as placing flat stone slabs (galets), deposits from an ancient glaciation, beneath vines to absorb heat from the sun.

The term “well drained soil” can be a bit misleading. If rain- or snow-melt filters through the soil too rapidly, neither the plants or microbiota will be able to intercept the water and its nutrients; in this case nutrients are flushed through the soil into the watertable. If drainage is too slow then conditions can develop that are more favourable to toxins. It’s a bit like your backyard compost; if it has an unpleasant smell then it isn’t working (the organic matter is rotting instead of breaking down into useful components). Soil drainage is a balancing act, and an important part of the act is how a vintner looks after their dirt; too much or too many herbicides, insecticides, and compaction are probably their three worst enemies.

Soil pH is determined primarily by the parent material from which the mineral components of soils are derived. Most common parent rocks and other parent materials like flood plain sands and gravels, or volcanic ash, result in neutral to slightly acidic soils; those developed on limestones slightly alkaline. Rain also tends to be slightly acidic (because of dissolved carbon dioxide), and this property helps to release from minerals in the parent material, potassium (mainly from feldspars and clay minerals), phosporous (from clays and a mineral called apatite), plus important trace elements (like zinc, iron, copper, boron).

A soil’s microbiota is the real powerhouse of any soil; without them the organic (topsoil) part of soils would not exist. Microbiota, especially bacteria and fungi are responsible for virtually all nutrient transfer to plants. They do this by converting nutrients like nitrogen to water soluble compounds; plants do not absorb nitrogen directly from the air – they do so via nitrates (1 nitrogen atom bonded to 3 oxygens), and it is the nitrogen fixers (especially symbiotic fungi) that do this. The microbiota thrives in the organic topsoil, in fact it is largely responsible for creating the topsoil because they mediate many of the chemical reactions that break organic matter down to humus. It’s worth keeping this in mind the next time you are tempted to nuke a bunch of weeds with glyphosate; you will also get rid of some microbiota.

Terroir with possums

I worked one summer recess in a vineyard north of Auckland. This was about 47 years ago and back then the choice of wines in New Zealand was very limited. This job was an eye-opener for an early 1970s university student whose total experience with wine was cheap sauternes and 50 cent flagons of ghastly sherry. On one occasion we were tasked with minor remediation work on one open vat that contained the new harvest. The grapes were beginning to ferment; there was a great deal of red froth liberally sprinkled with dead and inebriated bees and wasps. And smack in the middle of the tank was a possum. This, it turned out, was our task – to remove the dead creature (apparently the wasps were acceptable). At the time I had no inkling of terroir, but I now wonder if a wine taster back then had noticed anything unusual on the nose or the palate. I am pleased to report that, 47 years later, New Zealand wines, including from this particular vineyard, are world class.

As a geologist, I tend to identify with the kind of terroir that is an expression of the overall environment. The vintner’s culture and winemaker’s personality are superimposed on this. Even the foot-stomping grape-treaders may influence a wine’s character. Enjoyment of the final product can be simple or complicated. The concept of terroir, however you read it, adds a kind of window into this other world.