The term neomorphism is reserved for recrystallization of a mineral and its polymorphs to new crystal phases having the same composition. In calcium carbonates this involves recrystallization of calcite, high-magnesium calcite, and aragonite to calcite (usually low-magnesium calcite). Dolomites are also prone to neomorphism (dolomite to dolomite replacement); note that the replacement of calcite or aragonite by dolomite is not a neomorphic process. Neomorphism commonly results in an increase in crystal size and the destruction or overprinting of original fabrics.

The actual process of neomorphism is still a bit of mystery. Initiation of recrystallization begins with dissolution at the crystal-fluid interface. Subsequent precipitation must involve changes in the local thermodynamic conditions (such as increased saturation, or a change in the activity of carbonate species). If crystal size continues to increase (via syntaxial growth) then the transfer of dissolved mass to the crystal interface must continue.

Neomorphic versus cement textures

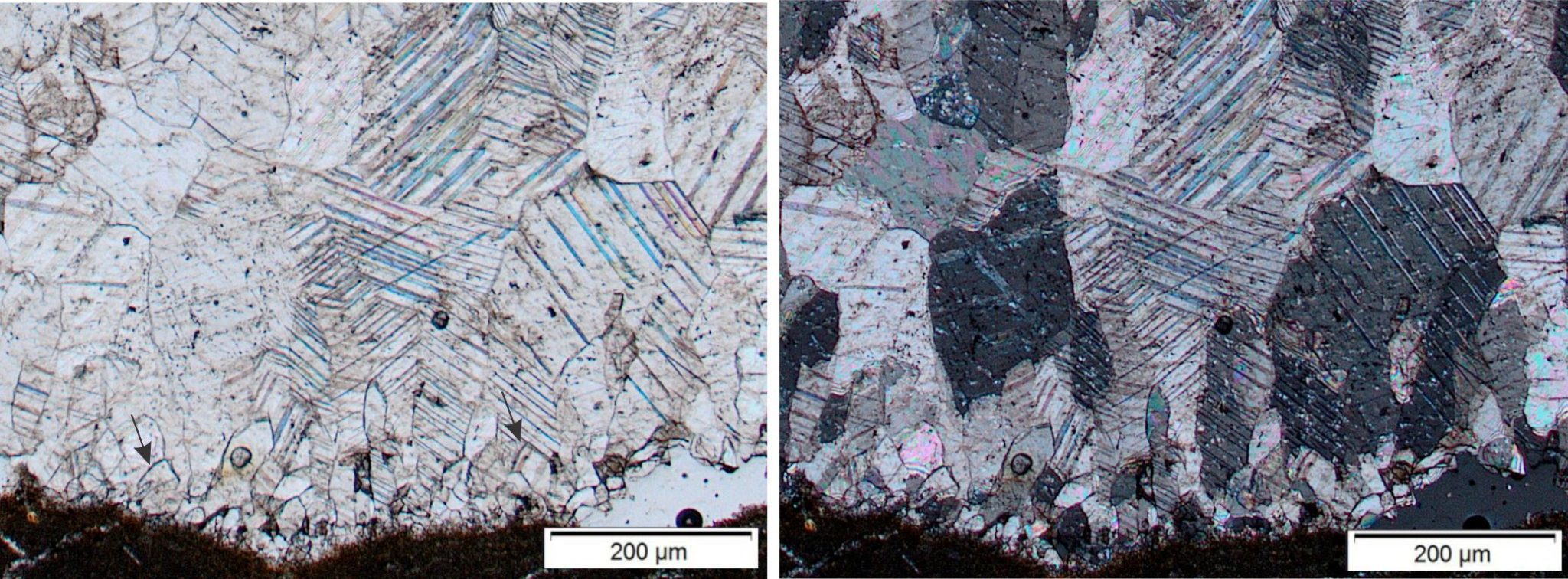

Cements grow by precipitating into the available inter- or intragranular pore space. Thus, crystal faces are free to grow and therefore they tend to be planar, with sharp crystal edges and terminations. In contrast, the locus of neomorphic replacement of pre-existing crystal masses (e.g., cements, bioclasts) and subsequent precipitation will tend to be focused along crystal discontinuities such as cleavage and twin planes, as well as crystal edges and terminations, in part because they are regions of higher surface free energy. Thus, neomorphic crystal boundaries are commonly irregular and characterised by embayments, re-entrants, or segmented.

Neomorphic replacement of carbonate cements, bioclasts, microbial laminates, and mudrocks commonly proceeds fastest in fine-grained deposits such as micrite – again this may be a function of higher surface free energies relative to much larger crystals and coarse-grained clasts.

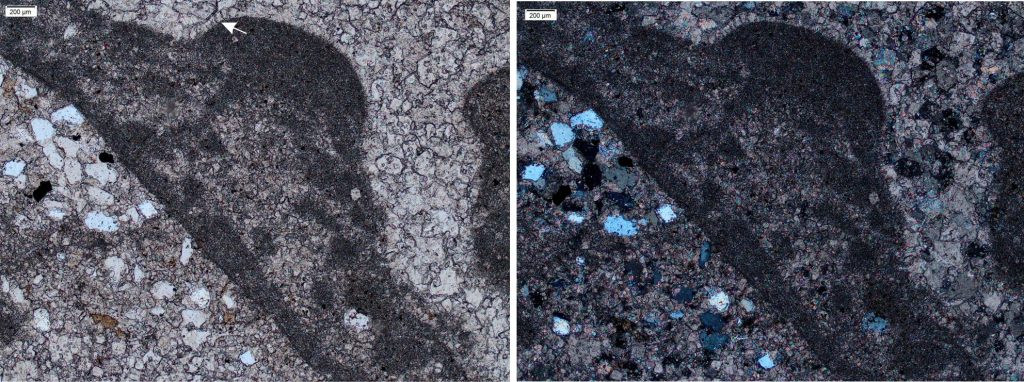

Recrystallization may also show a progressive change in crystal size – referred to as aggrading neomorphism. Crystal aggradation can mimic pre-existing cement fabrics where crystal size increases from the cement boundary into pore spaces. Aggrading neomorphism is common in carbonate mudrocks; the resulting textures appear clotted, where remnant patches of micrite appear to float among clusters of coarser crystals. This kind of texture is also called structure grumeleuse after Lucien Cayeux. Clotted textures may also be pellet-like; the distinction between original peloidal textures and these neomorphic fabrics requires careful attention. Neomorphic fabrics frequently cut across cement and clast boundaries.

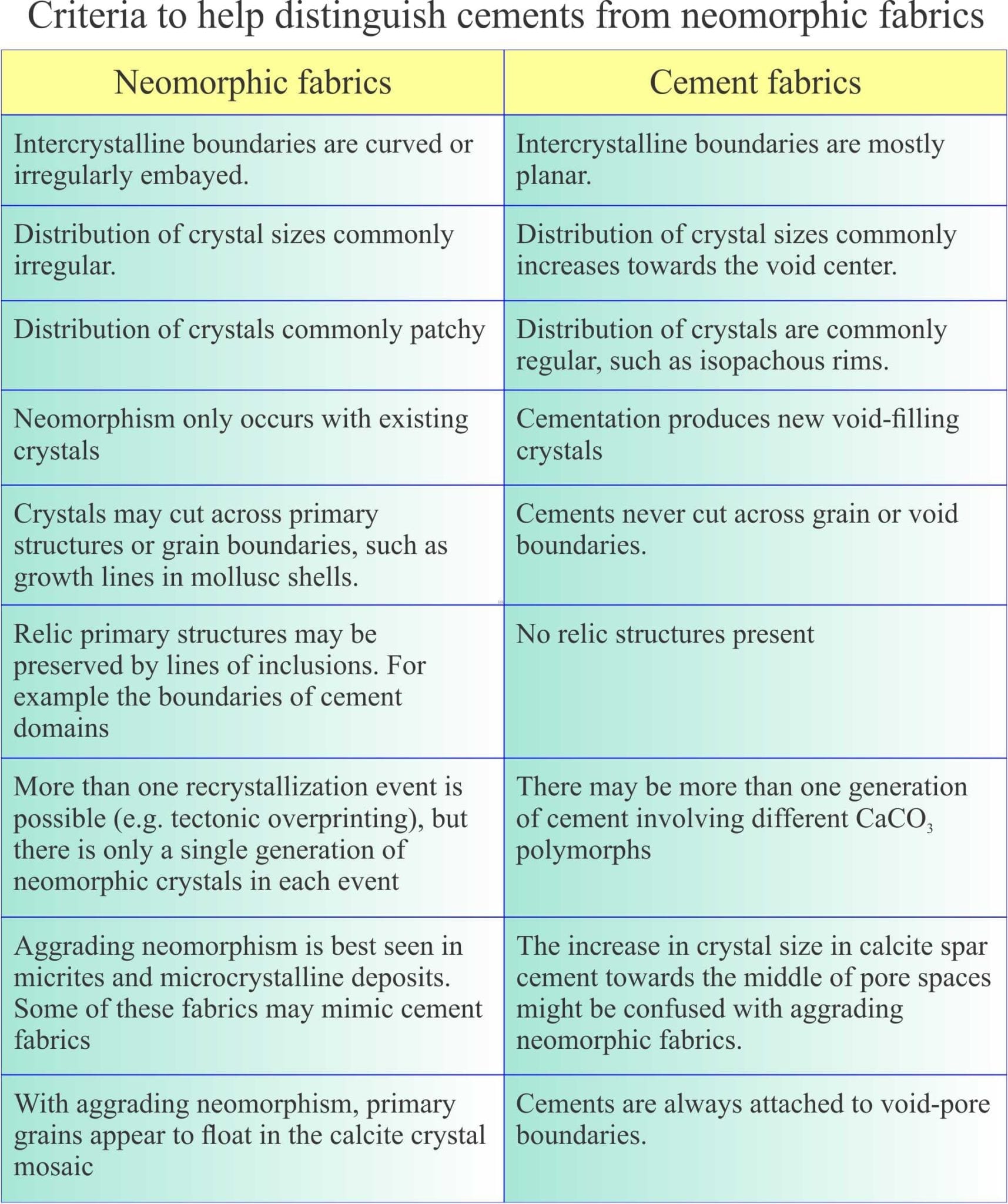

Some criteria that distinguish neomorphic from cement fabrics are listed below; the information is gleaned from R.L. Folk (1968), Robin G.C. Bathurst Chapter 12 (1976), J.W. Morse and F.T. Mackenzie 1990, and Erik Flugel. (2010, Chapter 7).

And in thin section…

Intercrystal boundaries in cements

Neomorphic fabrics

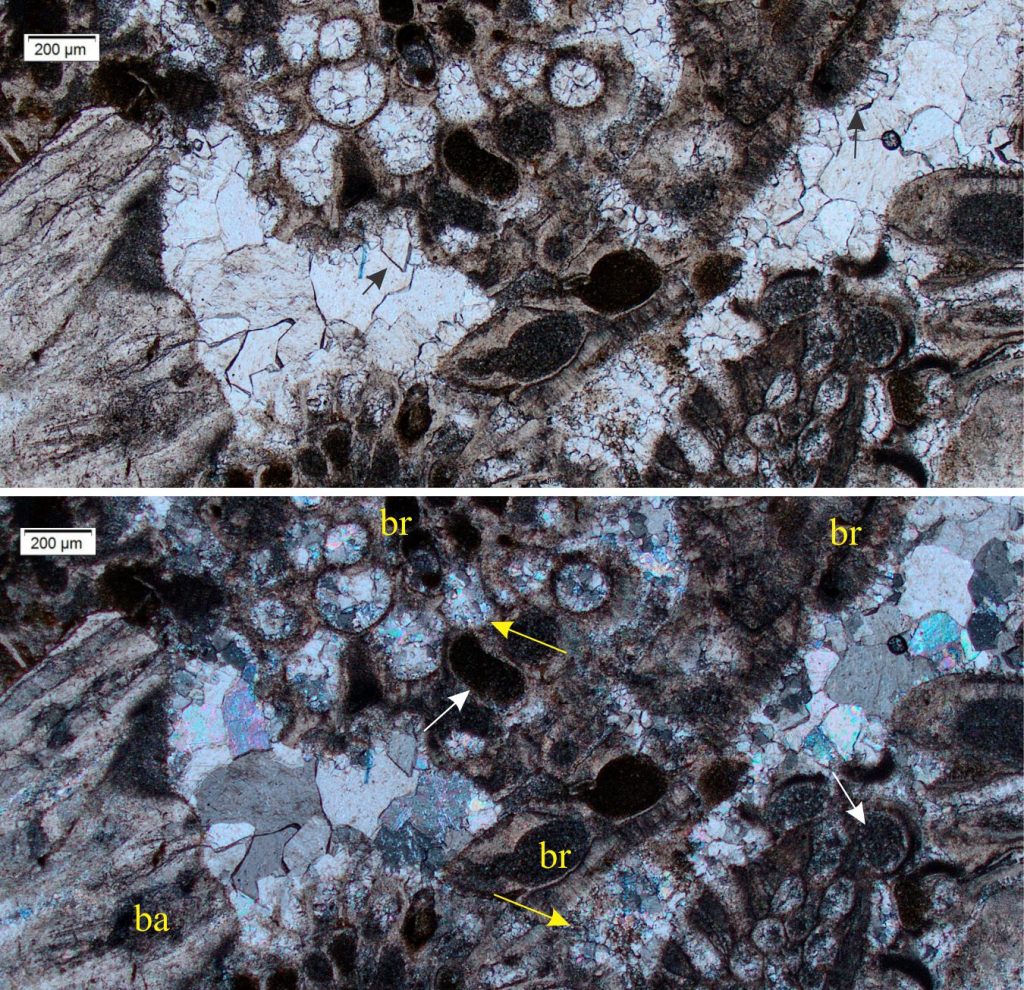

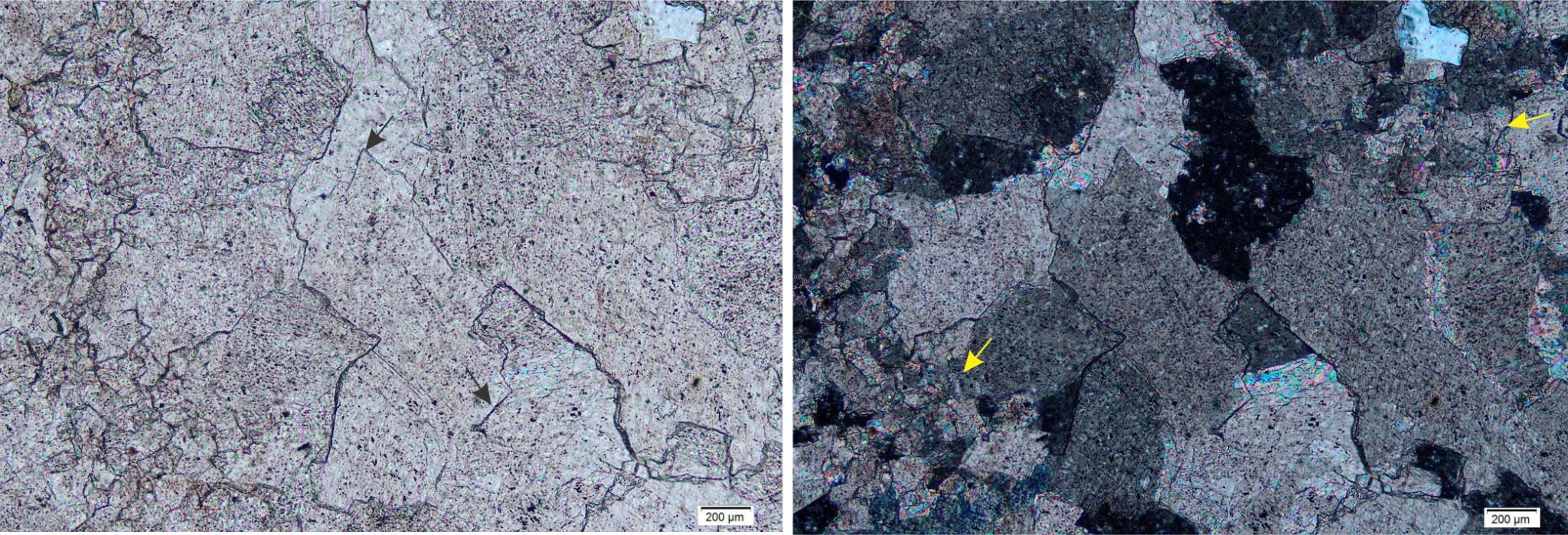

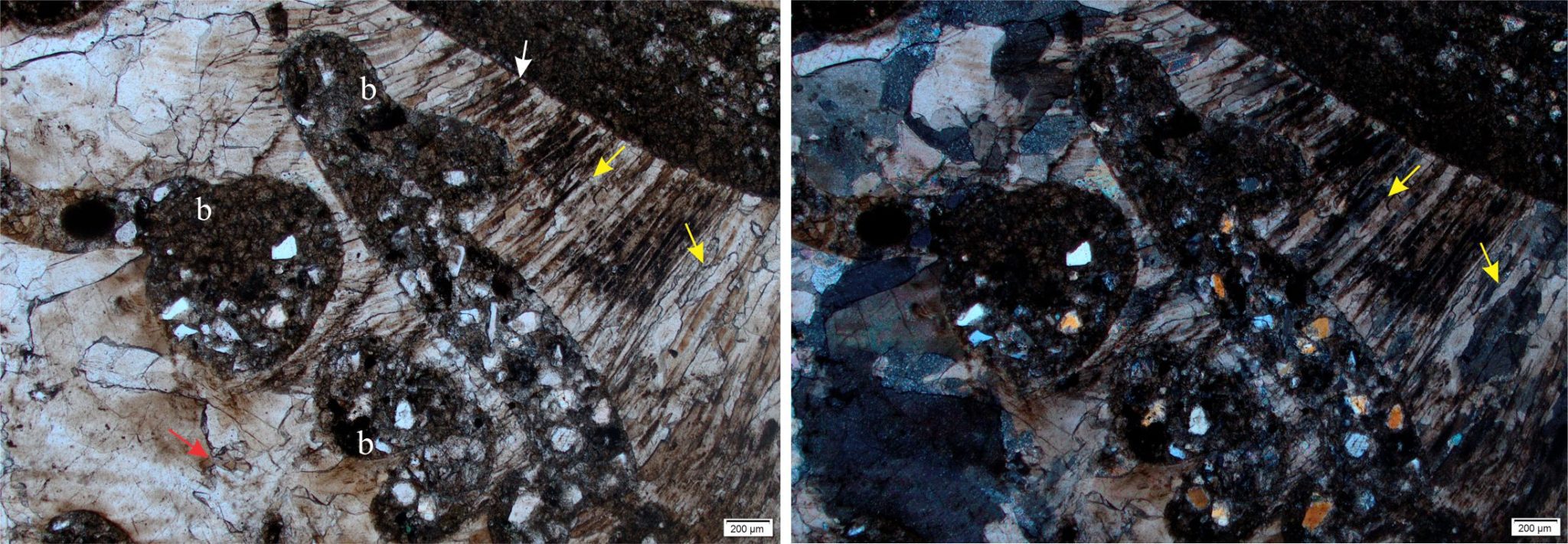

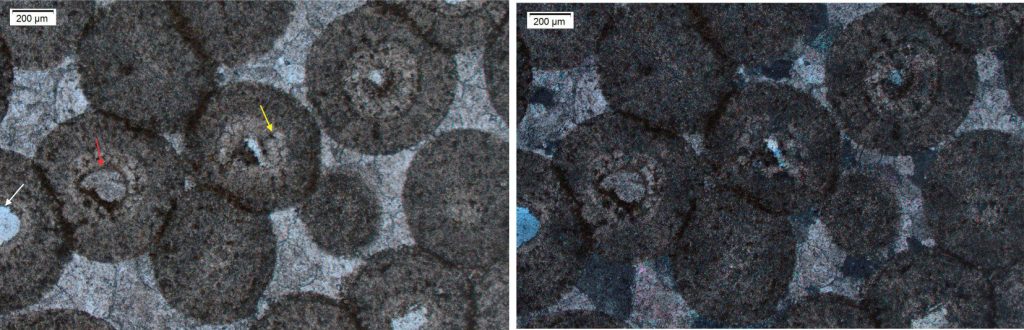

Inter- and intragranular calcite spar cements in Oligocene barnacle (ba) – bryozoa (br) limestone. Some of the smaller crystals lining bioclast rims have scalenohedral terminations (back arrows). The bryozoan intragranular zooid pores are filled with dark brown micrite (white arrows), but in some the micrite has recrystallized to calcite spar (yellow arrows). In this case, crystal boundaries are less distinct because the neomorphic spar is intergrown with remnant micrite. Top: Plain polarized light. Bottom: Crossed polars.

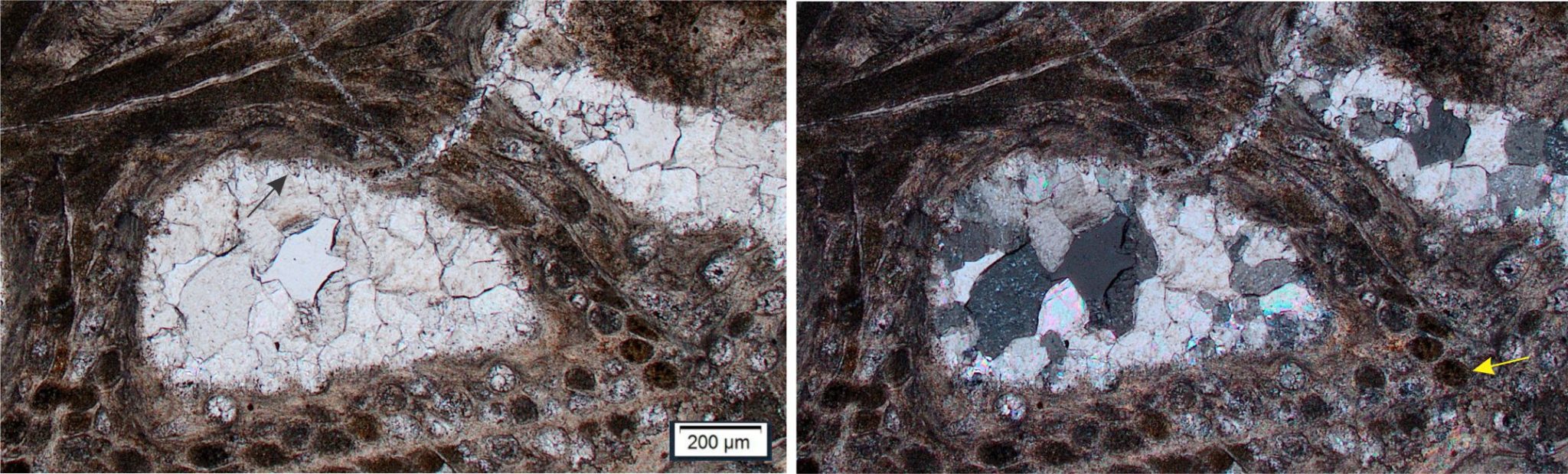

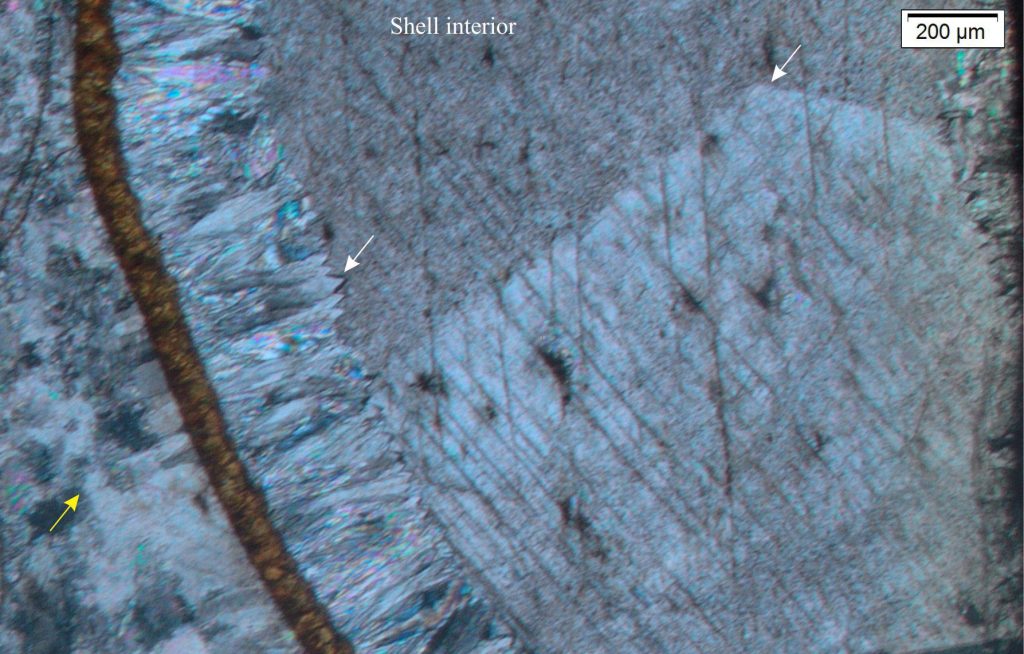

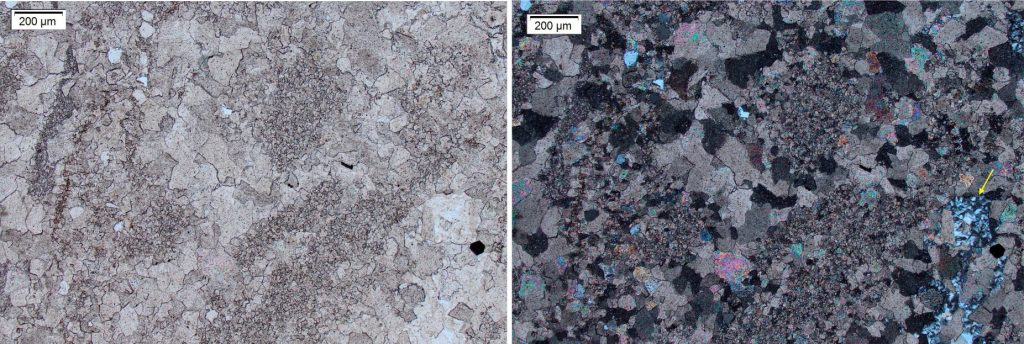

Neomorphic fabrics in the (possibly aragonitic) shell preserve some of the original crossed-lamellar structures that parallel the shell wall (yellow arrow). Crystal boundaries are highly irregular, producing an irregular interlocking framework. In contrast, cementation of the shell interior (where the animal once resided) began with isopachous, scalenohedral calcite that was followed by coarse calcite spar. The skinny brown layer is the interior shell wall, now replaced by siderite. Crossed polars.

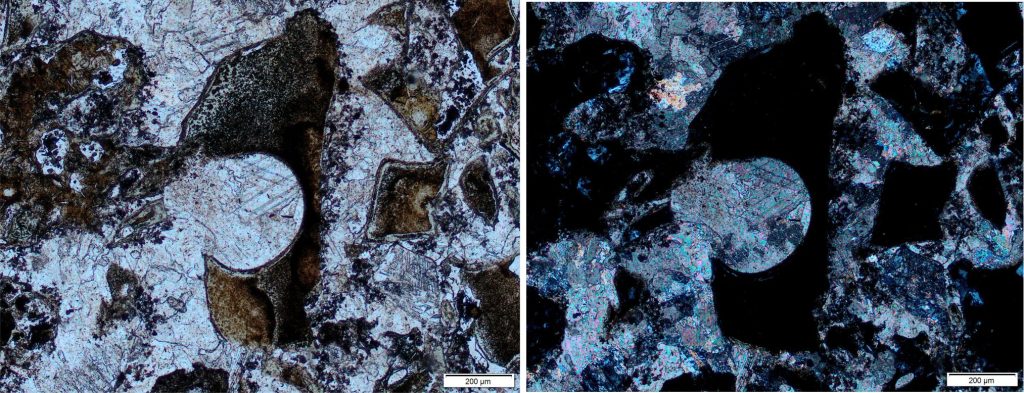

The shell borings are filled with mud and silt-sized quartz and lithic grains, derived from the host sediment. Jurassic Bowser Basin. Left: Plain polarized light. Right: Crossed polars.

Aggrading neomorphism

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Annette Rogers and Kirsty Vincent, Geology at Waikato University, for access to the petrographic microscope.

Other posts in this series

Optical mineralogy: Some terminology

Carbonates in thin section: Forams and Sponges

Carbonates in thin section: Bryozoans

Carbonates in thin section: Echinoderms and barnacles

Carbonates in thin section: Molluscan bioclasts

Mineralogy of carbonates; skeletal grains

Mineralogy of carbonates; non-skeletal grains

Mineralogy of carbonates; lime mud

Mineralogy of carbonates; classification

Mineralogy of carbonates; carbonate factories

Mineralogy of carbonates; basic geochemistry

Mineralogy of carbonates; cements

Mineralogy of carbonates; sea floor diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; Beachrock

Mineralogy of carbonates; deep sea diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; meteoric hydrogeology

Mineralogy of carbonates; Karst

Mineralogy of carbonates; Burial diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; Neomorphism