The interior of northern British Columbia is rugged, mountainous country. Roads, that tend to be quite rough were frequently opened to provide access to mines and small settlements. It is an isolated part of the world, beautiful, even majestic, but also unforgiving. East of the Coast Mountains and about 200km south of Yukon, is a huge swath of sedimentary rocks, referred to collectively as Bowser Basin. The rocks are Jurassic to Cretaceous, recording a history of about 70 million years duration. Humungous volumes of sediment were eroded from older rocks to the north, that were uplifted and deformed as tectonic plates, or terranes, collided with the ancient margin of North America. Gravel, sand and mud were carried by braided rivers, supplying coarse sand and gravel to the coast and beyond, and to large deltas that supported lush forests (later converted to coal).

My four-year involvement in this project began in 1989. It was part of a much larger Geological Survey of Canada program coordinated by Carol Evenchick, a structural geologist based in Vancouver. Large tracts of these strata had never been looked at, so it was basically open season. Much of the work was conducted in what is now Spatsizi Plateau and Stikine Provincial Parks.

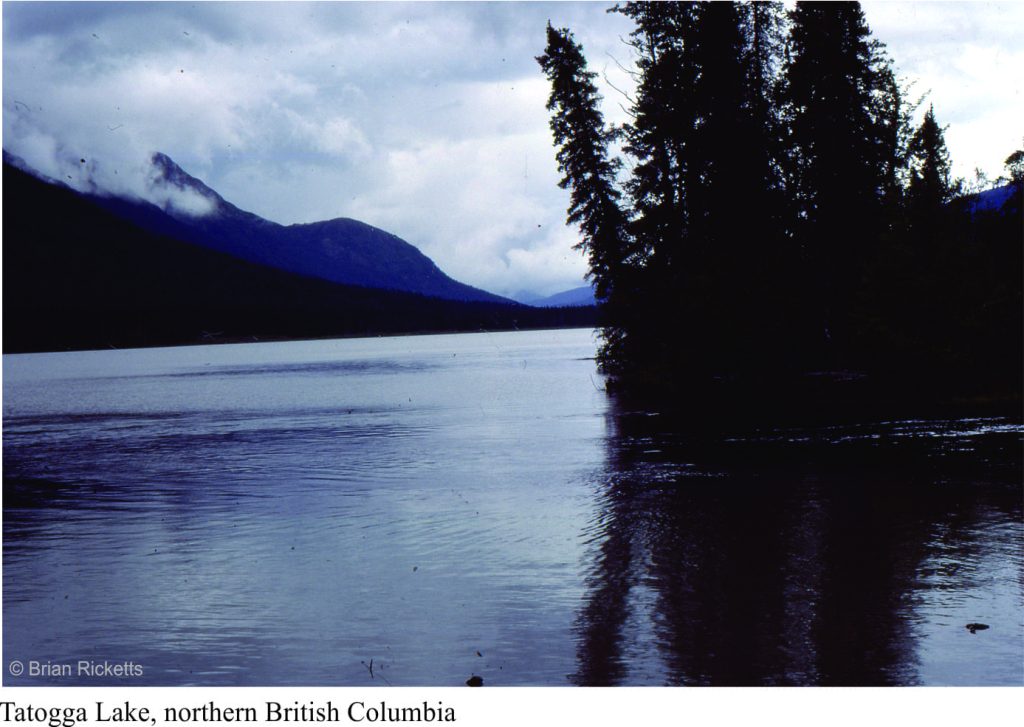

The drive from Vancouver, about 1700 km, takes 2-3 days, via Stewart and the Stewart-Cassiar Highway. Base-camp was a collection of aged trailers at Tatogga Lake, one of those idyllic northern lakes with the odd driftwood-strewn beach, and spruce dipping their boughs in the cold water. Next door to the camp, and on the main road (there is only one road) was a lodge, one of those typical northern log constructions (now called Tatogga Lake Resort). The look and smell of the place was such a welcome respite from days in the field; pancakes, fries and beer. It was run by Mike, a big guy who, when he wasn’t running the kitchen, hunted, fished and played guitar. The door leading to the kitchen was framed by two massive moose racks, locked together – two lives entwined, lived, fought, entangled in death. They were found that way. The new owners now boast WIFI and TV. In the late 80s there was one pay phone out back. I have heard since that Mike disappeared one winter, probably through the ice on some remote lake.

Tatogga Lake also saw the coming and going of visiting geologists. One colleague, a paleontologist, drove from Calgary. I expected him to be tired, but when he alighted from his truck, his eyes were teary. “Long journey?” I asked. Yes, but the reason for his blubbering – he’d been listening to Patsy Cline for three days.

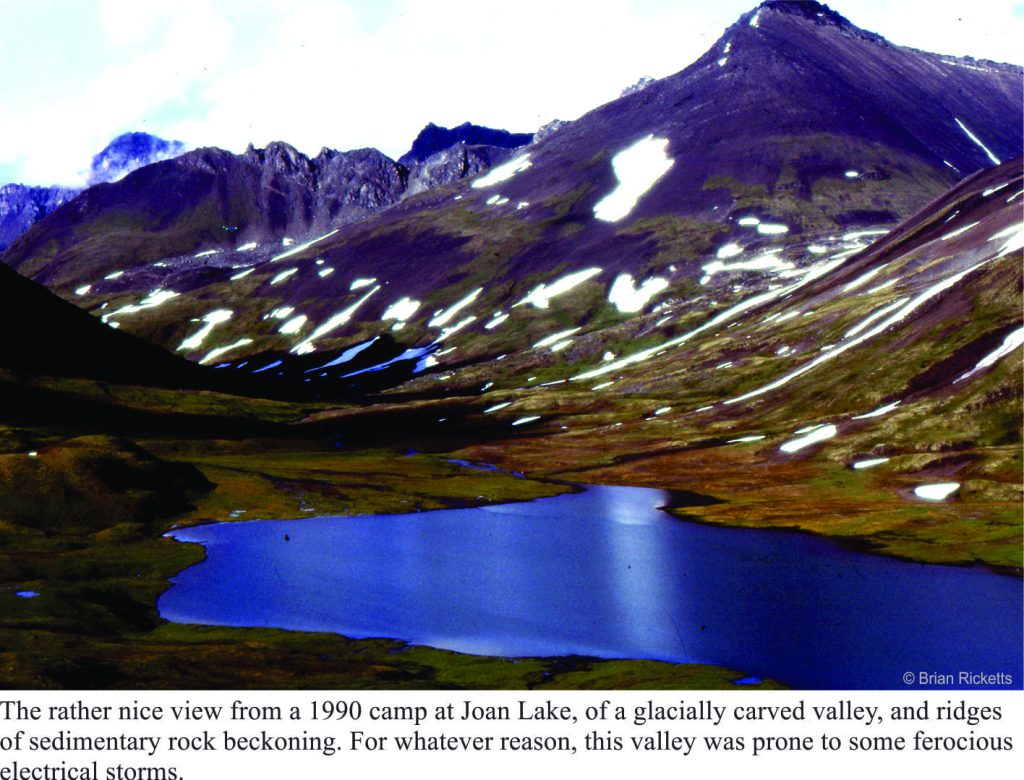

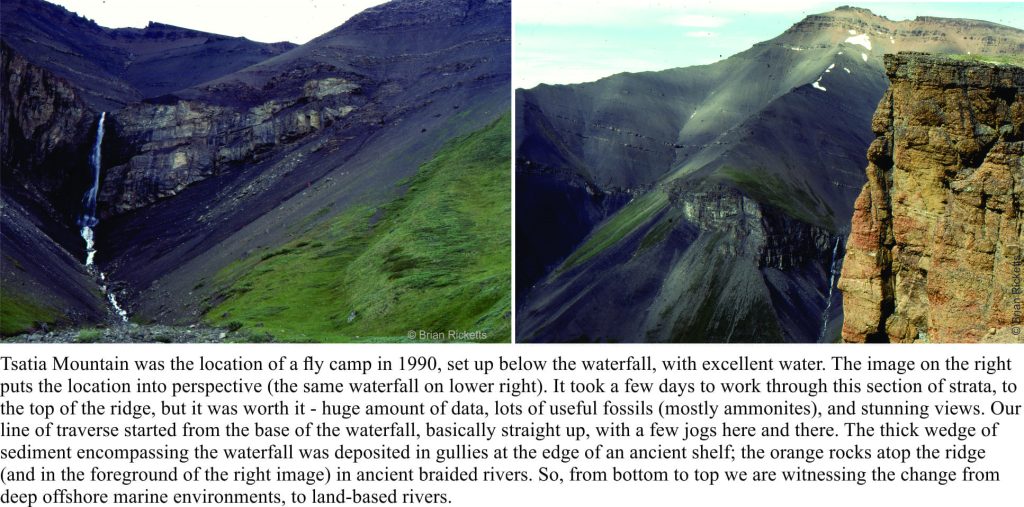

Working the ridges above the tree-line didn’t just provide access to exposed rocks, it gave one a whole new perspective on the geology; you could see for miles. This is where we sat with topography maps and aerial photos, tracking thick packages of sedimentary rock, and contemplating the structural complexities of distorted, folded and faulted strata. Field geology in the mountains means a lot of walking and climbing; up, down, and along rocky outcrops. One eye on the rocks, the other on the weather. Like any mountainous region, the weather can change in a blink. Summers there usually meant quite decent weather, but occasionally the rain, cloud and fog would set in, or electrical storms would attack the ridge tops. You could see the storms blasting their way across distant ridges. This is where field assistants with long straight hair were particularly useful. Standing exposed on a ridge with a building charge of static electricity was distinctly uncomfortable. It was time to make for lower ground when their hair stood on end. Steel geology hammers and other metal objects were left on prominent rocks while we clambered downhill, seeking shelter.

My only close encounter with a Grizzly bear was in these mountains. The weather on one fly-camp turned wet, with our field area completely enveloped in cloud for two days. As is usually the case in situations like this, one catches up on sleep, chats, and drinks warm beverages. The latter requires relief. Answering the call, I stepped outside the communal tent and wandered some metres away (there is decorum even in the mountains). My eye caught movement, and out of the fog walked, slowly, a grizzly mom and two cubs. They were probably 10-20 metres away; I would have preferred a much greater separation. Mom stopped, her head lowered, moving slowly from side to side. This was not an encouraging sign, so without making too much noise, I asked the guys if they could get the gun. There was some disbelieving banter from my three compatriots, that stopped when one of them poked her head out the tent door. Some rustling, and the response “the gun is in the other tent”. Bugger! Perhaps it was the noise from the others, but the bruin trio slowly ambled off, climbing the ridge and disappearing in the mists. I required more relief.

Back at base-camp, there were always chores, catching up, phone calls home, and visiting Mike. The 1991 season saw a very resourceful group of field assistants (all students from various universities). In addition to acting as weather vanes, this group decided to construct a sauna out of old timbers and tarpaulins. It worked, until it caught fire. Fortunately, no one was hurt, and the damage was limited except for the one or two deflated egos. However, the incident did signal that it was time to head back into the field, to direct their enthusiasm in more profitable ways.