This biography is part of the series Pioneering women in Earth Sciences – the link will take you to the main page.

Mary Buckland, born Mary Morland, Abingdon, Berkshire.

Mary Buckland’s reputation seems to have hung thread-like from her husband William Buckland’s position as an eminent figure in Victorian ecclesiastical and scientific circles (twice President of The Geological Society). Like many wives of many eminent men, Mary acted as confident, someone who could hold her own in scientific discussions, rock collector, and gifted illustrator, but was never included in her husband’s many publications except as a footnote or acknowledged contribution to his illustrations. And yet, like many wives of many eminent men, her contributions were outstanding.

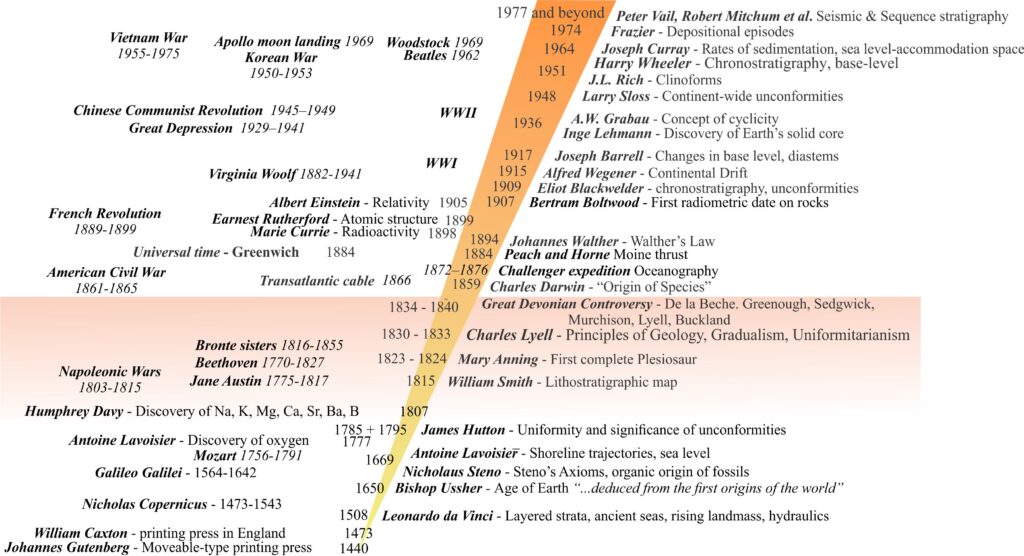

Fortuitously, Mary (then Moreland) was shunted off to live in Oxford after her mother died, to live with Regis Professor Sir Christopher Pegge and his wife. Pegge was an anatomist who also lectured in geology. She was immersed in a world of scientific curiosity and discussion, cabinets filled with rock and fossil samples, notebooks and sketch books. Presumably she accompanied Pegge on field excursions because she developed skills at collecting, and illustration that included line drawing and watercolour painting. Pegge clearly was impressed because he left his entire collection of rocks and books to her when he died in 1822; Mary was then 25. At this point in her life, Morland had already created illustrations for William Buckland (before they married), Georges Cuvier and William Conybeare – I’m guessing that Pegge had a hand in introducing and procuring this work, through his academic and gentlemanly contacts.

Her association with William Buckland apparently began in a carriage according to their daughter, Mrs. Gordon who in a biography of her father wrote “…Dr Buckland was once travelling somewhere in Dorsetshire, and reading a new and weighty book of Cuvier’s which he had just received from the publisher; a lady was also in the coach, and amongst her books was this identical one, which Cuvier had sent her. They got into conversation, the drift of which was so peculiar that Dr Buckland at last exclaimed, ‘You must be Miss Morland, to whom I am about to deliver a letter of introduction’.” (quoted in Kölbl-Ebert, 1997).

Her marriage to Buckland in 1825 began something of a disconnect between her passion for geology and the expected contribution to family life where, in between her role as proof-reader-in-chief for his manuscripts, she found time to bear 9 children. True to the social mores of the time, William also opined that wives shouldn’t be involved in the rough-and-tumble of scientific discourse, although he had no qualms about using her various talents for the purpose of scientific advancement (Kölbl-Ebert, 1997; Nina Morgan, 2019). It is likely she was the primary proof-reader for William’s contribution to the Bridgewater Treatises, an 8 volume series that contained descriptions and explanations of the known universe as extensions of God’s knowledge and wisdom (although a search of both volumes failed to generate any reference to Mary): William Buckland. Treatise VI. Geology and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology (2 volumes; 1837).

References and other documents

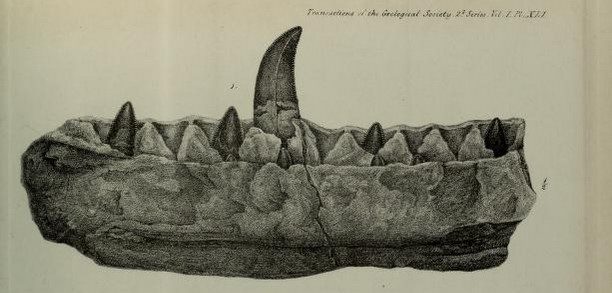

William Buckland, 1824. XXI.—Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield. Transactions of the Geological Society of London, Series 2, Volume 1, p. 390 – 396.

Martina Kölbl-Ebert, 1997. Mary Buckland, née Morland 1797–1857. Earth Sciences History., 16, 33–38.

H. Torrens, 2008). Buckland [née Morland], Mary (1797–1857), geological artist and curator. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Nina Morgan, 2019. Distant Thunder: Behind every good man…. Geoscientist v. 29 (6), 26.

Susan Newell, Mary Morland, University of Oxford Museum of Natural History.