This biography is part of the series Pioneering women in Earth Sciences – the link will take you to the main page.

Born: Lyme Regis.

The last few decades have seen Mary Anning reach almost legendary status as fossil discoverer, collector, analyst, and communicator (perhaps more so than any other woman geoscientist). She is feted in learned papers, books, and a movie (Ammonite), all teasing apart her social and financial predicament, her scientific skills, and the ignominy of being largely ignored by leading scientists of her time – scientists and wealthy collectors who would willingly use her skills and specimen fossils but failed by commission to publicly recognize and credit her discoveries and intellectual prowess.

Mary Anning was not what Victorian society would have regarded as an ‘ideal’ woman. She was born into poverty, and rarely extricated herself and her family from this status. She sold fossils for a meagre living. She constantly dirtied the hems of her skirts while digging through the Blue Lias. She argued with some of the leading scientists of the day – Georges Cuvier, William Buckland, Henry De la Beche, William Conybeare. It seems that Buckland and De la Beche raised funds to assist her, but a cynic might argue that they did this so she could continue to supply them with additional specimens – perhaps that’s being unfair.

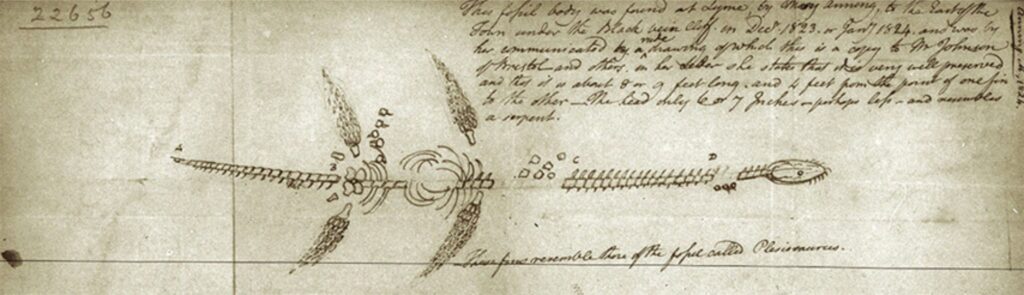

Mary, along with her brother, unearthed some of the first specimens of Ichthyosaurus; she discovered the first Plesiosaur in 1823. These discoveries are largely the basis for her now popular status. But her acknowledged expertise also extended to Jurassic stratigraphy, ammonites and other molluscan faunas, and interestingly coprolites.

One of her close friends, Charlotte Murchison, who stayed with Mary for several weeks, also became an avid collector. Mary even stayed with the Murchison’s on her only trip to London in 1829 – a trip that included visits to the British Museum and Geological Society that displayed many of the specimens she had collected but none of the identifying labels credited her. Charlotte’s husband, Roderick Murchison, gave a presidential address to the Geological Society of London in 1832 making note of recent discoveries in paleontology, specifically the fossil reptiles, but made no mention of Mary Anning’s role in their discovery and descriptions.

She died from breast cancer in 1847 at only 47 and was buried at St Michael the Archangel Churchyard in Lyme Regis. She was listed by the Royal Society as one of the 10 most important British women to have influenced science. Henry De la Beche included an obituary in his address to the Geological Society of London in February, 1848… (from Taylor and Benton, 2023).

“I cannot close this notice of our losses by death without adverting to that of one, who though not placed among even the easier classes of society, but who had to earn her daily bread by her labour, yet contributed by her talents and untiring researches in no small degree to our knowledge of the great Enalio-saurians, and other forms of organic life entombed in the vicinity of Lyme Regis. MARY ANNING was the daughter of Richard Anning, …”.

References and other documents

H. Torrens, 1995. Mary Anning (1799-1847) of Lyme; “the greatest fossilist the world ever knew'”, Presidential Address. British Journal for the History of Science, 28, 257-284. PDF.

Marie-Claire Eylott. Mary Anning: the unsung hero of fossil discovery. Natural History Museum.

S. Turner, C.V. Burek, R.T.J. Moody, 2010. Forgotten women in an extinct saurian (man’s) world. In, Moody, R. T. J., Buffetaut, E., Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. (eds) Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 343, 111–153. PDF

M.A. Taylor and M.J. Benton, 2023. The Life of Mary Anning, Fossil Collector of Lyme Regis: a Contemporary Biographical Memoir by George Roberts. Journal of the Geological Society, Volume 180. Open Access.