The history of science is littered with the misplaced contributions by women, contributions that at best were pushed aside or ignored, and at worst thought of as shrill outbursts. Witness:

- Rosalind Franklin’s fraught journey to DNA’s double helix,

- the recent unveiling of Eunice Foote’s experimental discovery of the greenhouse effect of CO2, and

- Bell Bernell’s discovery of pulsars,

as corrections to a history where women found it difficult to escape the status of ‘footnote’. We can add Marie Tharp (1920-2006) to the growing list of corrections. In 1952 Tharp discovered the central rift system in the mid-Atlantic Ocean ridge (that later would become a critical component of sea floor spreading and plate tectonics) but for many years was regarded as a minor player in the burgeoning, post-war field of oceanography.

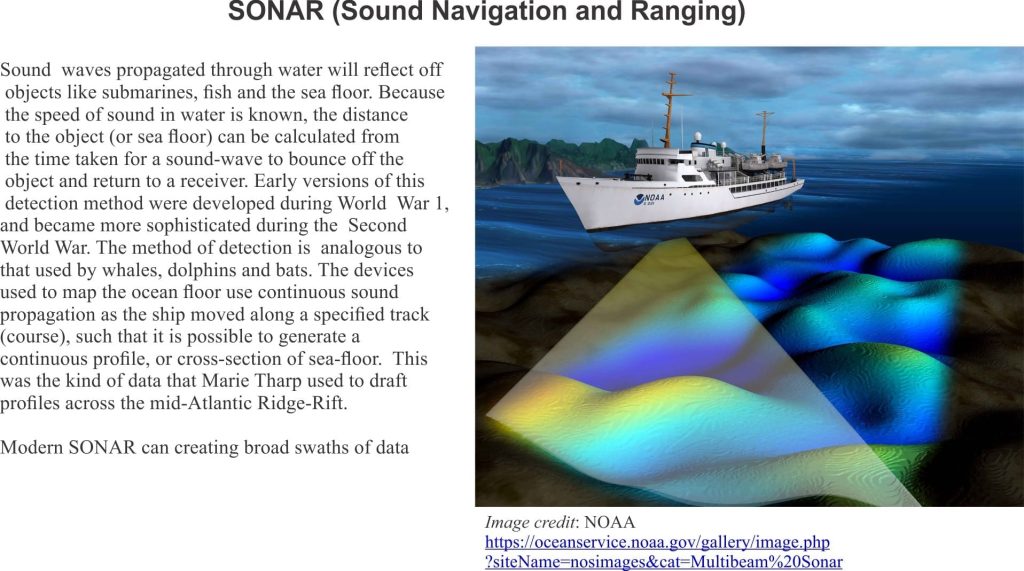

During the War, Tharp in her early twenties took advantage of opportunities to engage in university study, openings in science and engineering left by men who had gone to battle. She completed a Master’s degree in geology, but given that geology is a field-based discipline, and that women weren’t supposed to go into the field, she extended her studies to a Master’s in mathematics. In 1948 Lamont Geological Laboratory (now Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory) hired 28 year-old Tharp to draft maps of the Atlantic ocean floor, based on the growing database from SONAR and historical soundings. She worked with well-known geologist-oceanographer Bruce Heezen, who spent much of his time at sea. It must have been tedious work, but she counted herself lucky to have a position at all. This was a time when very few American universities (or anywhere else for that matter) offered science and engineering positions to women; a time of patriarchal condescension – “Mad Men” versus “Hidden Figures”.

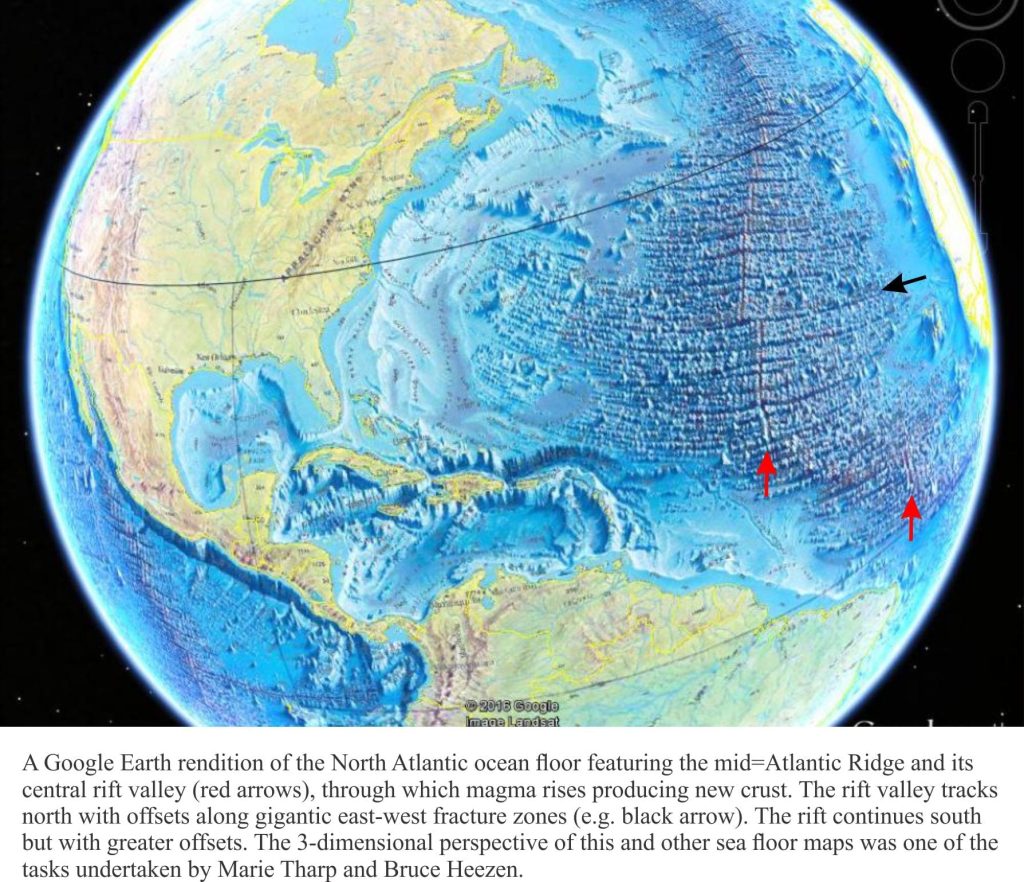

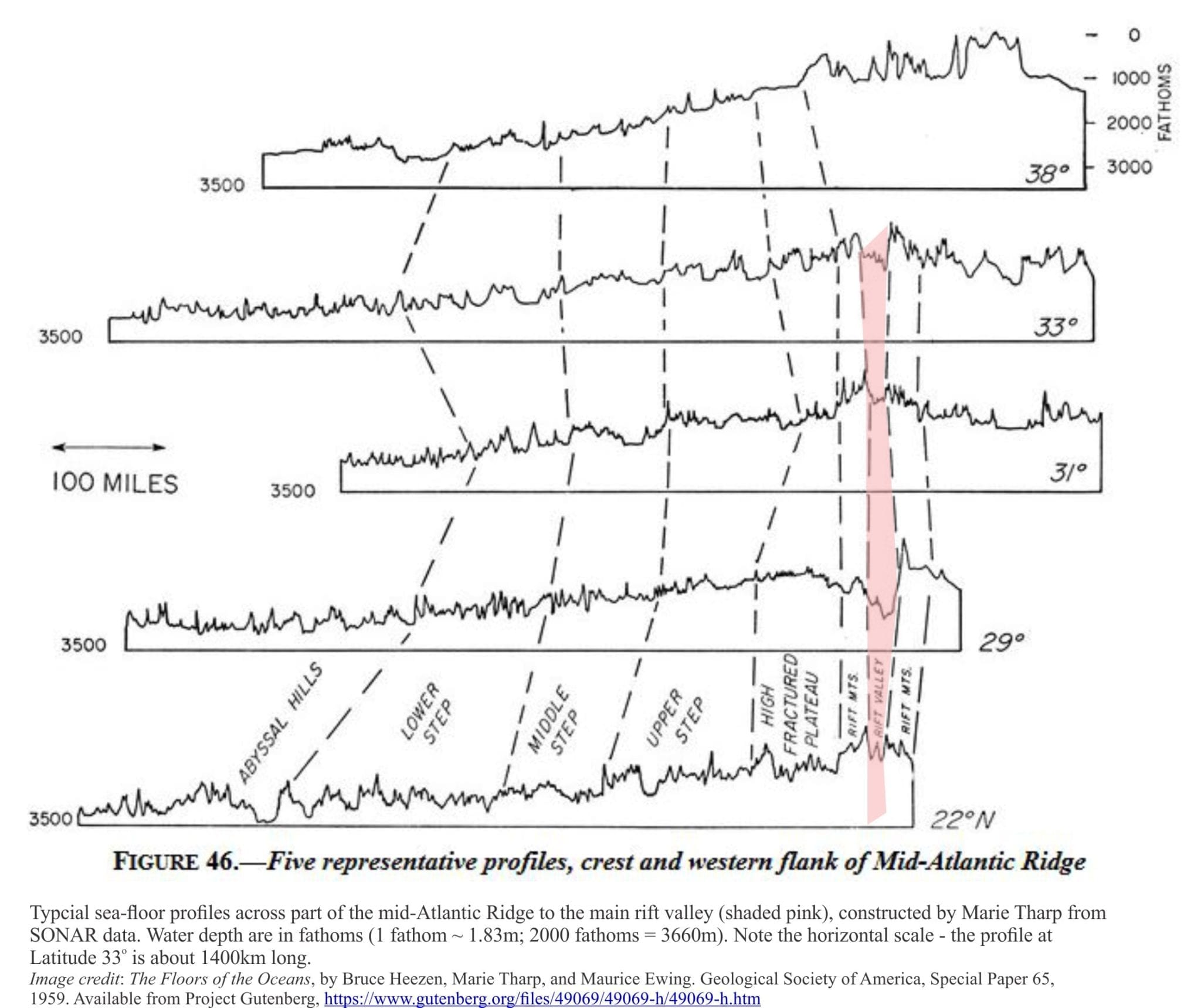

Tharp poured over depth and positional data for years, constructing 2-dimensional profiles of the Atlantic Ocean floor. She was aware, as other oceanographers were that an elevated region of sea floor apparently separated east and west Atlantic. This was initially mapped in 1854 by US Navy oceanographer, geologist and cartographer Matthew Maury, and later confirmed with depth soundings taken during the HMS Challenger expeditions (1873-1876 – Challenger had 291 km of hemp onboard to do this kind of thing; the ridge is generally deeper than 2000m). Tharp wasn’t surprised to find the Atlantic ridge on her profiles. What did catch her attention was the rift-like valley in the central part of the ridge; a geomorphic structure that was consistent through all her profiles. She immediately recognized the importance of this, because it implied significant extension, a pulling apart of Earth’s crust in the middle of the ocean. At the time, the general consensus was that ocean floors were relatively benign, featureless expanses. Her discovery indicated otherwise.

According to Tharp’s bio the response by Heezen and his colleagues was that she was being a typical woman – you know, “girl talk”. One can imagine the coffee room banter; ‘she’s great at drafting cross-sections but should leave the interpretation to the more learned’.

However, after some months and more profiles all showing the same rift- like structure, Heezen gradually accepted that this was real. A turning point for Heezen was the coincidence of several mid-ocean earthquake epicenters along the ridge. This was mid 1953. He understood its potential significance, particularly for those who thought that the hypothesis of continental drift had some credence (Heezen was not initially one of those people).

Ocean bathymetry studies in other basins in the early 1950s (Indian Ocean, Red Sea) revealed similar mid-ocean rifts. Tharp had by this time surmised that a rift valley coursed its way almost continuously the entire length of North and South Atlantic, a distance of 16,000 km; it was the largest continuous structure on Earth. The Lamont Doherty group gradually realized that the Atlantic structure, together with those discovered in other ocean basins, represented a gigantic Earth-encircling system of mid-ocean rifts, more than 64,000 km long.

Heezen presented their research to a 1956 American Geophysical Union conference in Toronto. Marie Tharp barely received a mention. She did co-author a few subsequent publications as an ‘et al.’, but it was a kind of ‘also ran’; the accolades and approbation went Heezen’s way.

Tharp was fired by the Laboratory, the victim of a spat between Heezen and Lamont boss Maurice Ewing, but she continued to develop the maps at home. Marie continued to work in the background, as the humble and grateful recipient of a job she considered to be fascinating; “I worked in the background for most of my career as a scientist, but I have absolutely no resentments. I thought I was lucky to have a job that was so interesting”.

Marie Tharp was named one of the four great 20th century cartographers by the Library of Congress in 1997, was presented with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Women Pioneer in oceanography Award in 1999, and the Lamont-Doherty Heritage Award in 2001.

There is no question that Tharp’s discovery influenced the promotion of Continental Drift in the geoscience community. Alfred Wegener’s bold hypothesis (1915) had one major problem – there was no known mechanism that could move oceanic crust and continents around, like some precursor shuffle to a jigsaw puzzle. In 1929 Arthur Holmes posited a mechanism that involved large convection cells in the mantle, but this too lacked an important degree of empirical verification. Discovery of the mid-Atlantic rift provided a solution to this vexing problem, and in 1962 Harry Hess proposed that new magma, via mantle convection cells, was erupted from mid-ocean rifts allowing oceanic crust to spread outwards. This was Sea Floor Spreading, a precursor to the grand theory of Plate Tectonics – the tectonic shift in geological thinking wherein oceanic crust is created at mid-ocean rifts and consumed down subduction zones, with the continents playing tag.

Marie Tharp’s doggedness in her belief and understanding of mid-ocean rifting is now celebrated. It’s taken a few decades, but she is no longer a footnote.