Women naturalists in the 18th and 19th centuries who showed an inclination for geological science were commonly ‘directed’ towards a vocation in paleontology – the collection, identification, and curation of fossils. Their male colleagues frequently opined that such “tedious work” was suitable for the female temperament. Maria Ogilvie, later to become Maria Ogilvie Gordon, bucked this trend. She certainly used fossils in her geological mapping and structural analyses, but they were more a means to an end, as guides to correlating and unraveling the structurally complex, disconnected strata of the Dolomites in northern Italy – she is widely recognized as a pioneer of Alpine geology.

It is often the case, even today, that students come to Earth science accidentally or by dint of luck. Ogilvie Gordon began her studies at the London Royal Academy of Music in 1882. Whether it was memories of her childhood in the Scottish Highlands or some other circumstance, she decided to focus on science, beginning at Heriot-Watt College in Edinburgh, then moving to University College London. She graduated in 1890 with a gold medal degree in zoology, geology, and botany.

Continuing to advanced degrees was difficult for any woman at that time – in Britain and Europe. She was denied entry to the University of Berlin, but in 1891 the University of Munich allowed her to pursue studies on a private basis, although she was not permitted to sit in the same room as the male students – sitting in an adjacent room with the door open was acceptable. She probably stood out, walking purposefully through those university halls, upsetting the balance of male dominance; she was likely one of only a handful, or even the only woman in those lectures.

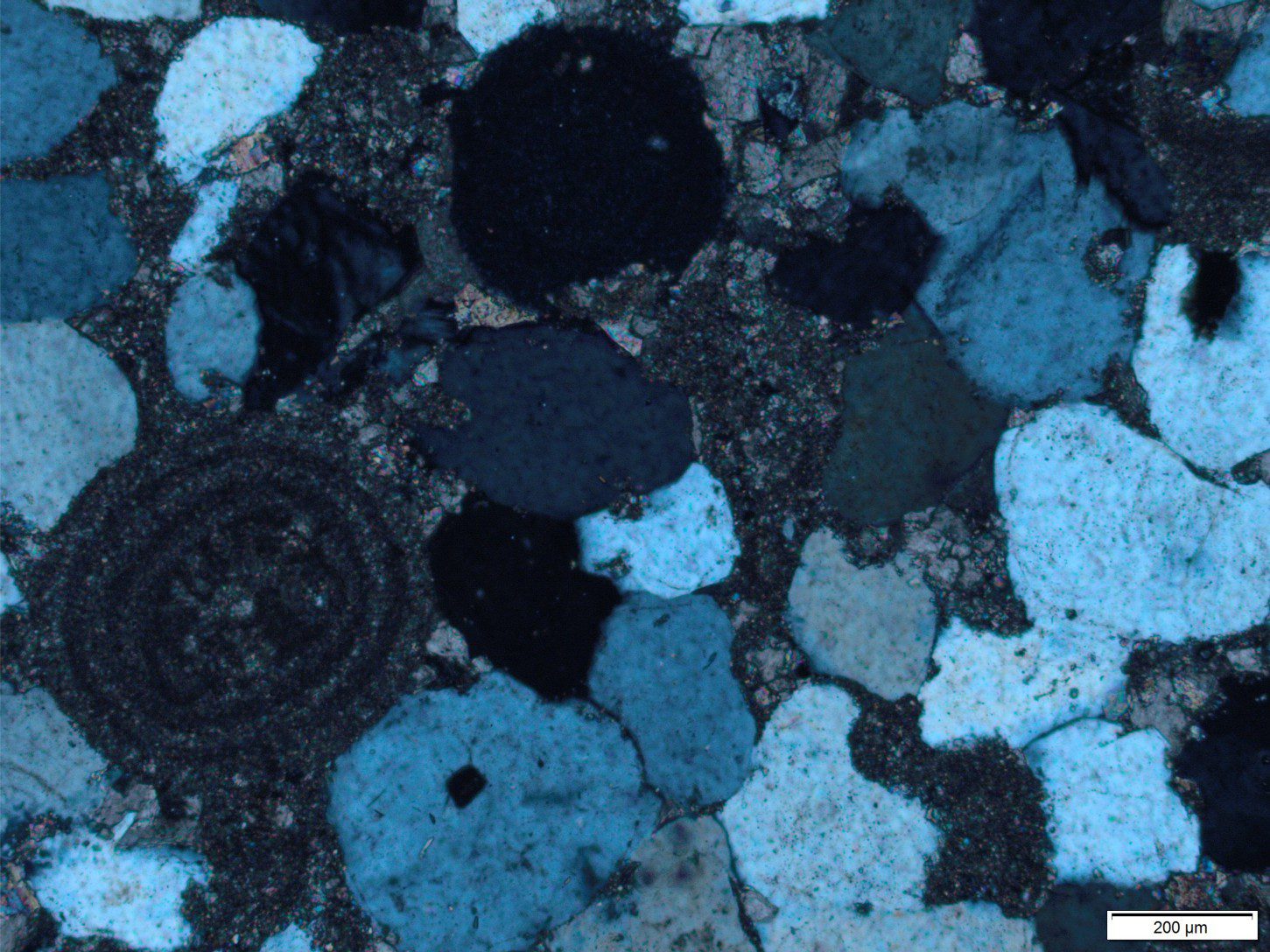

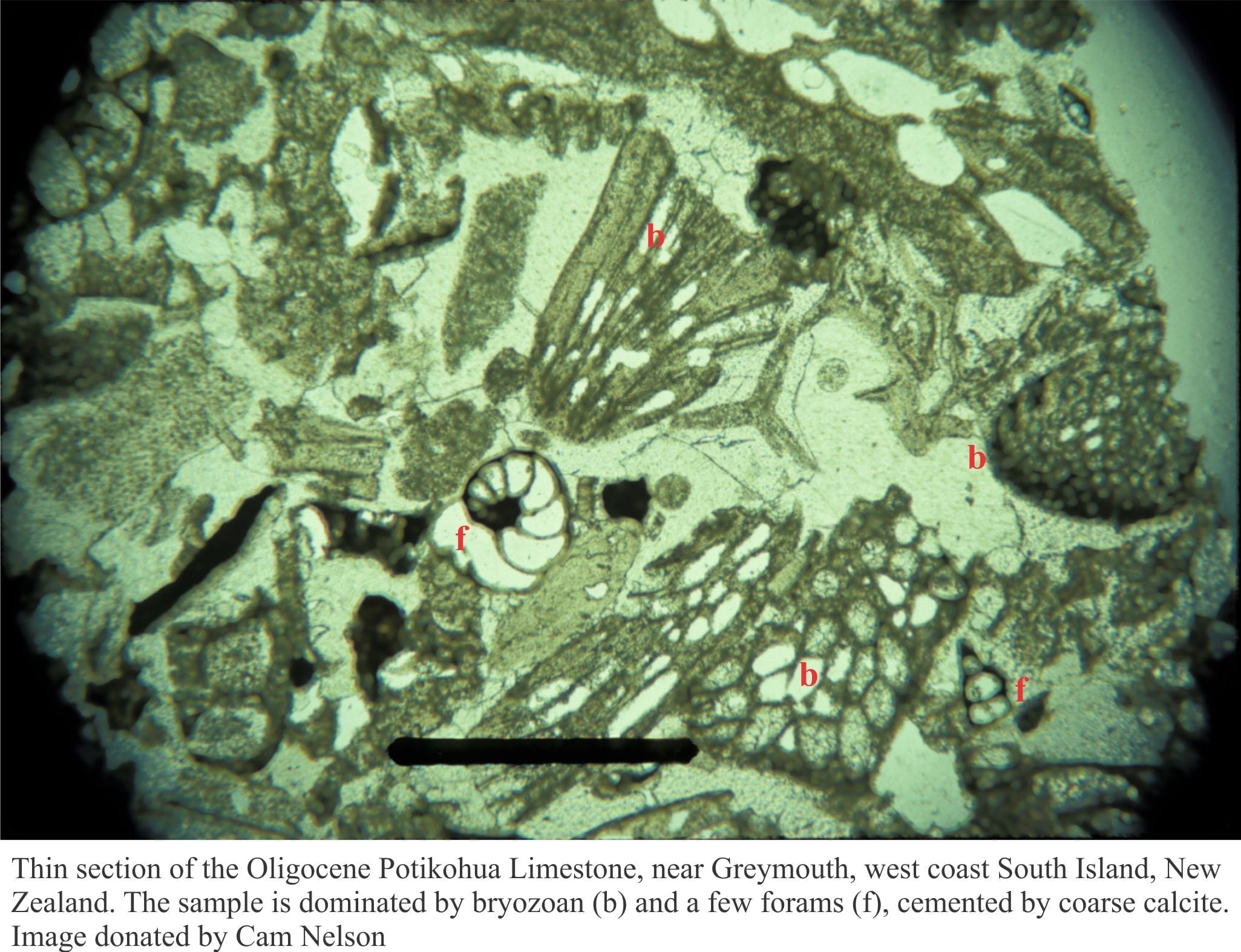

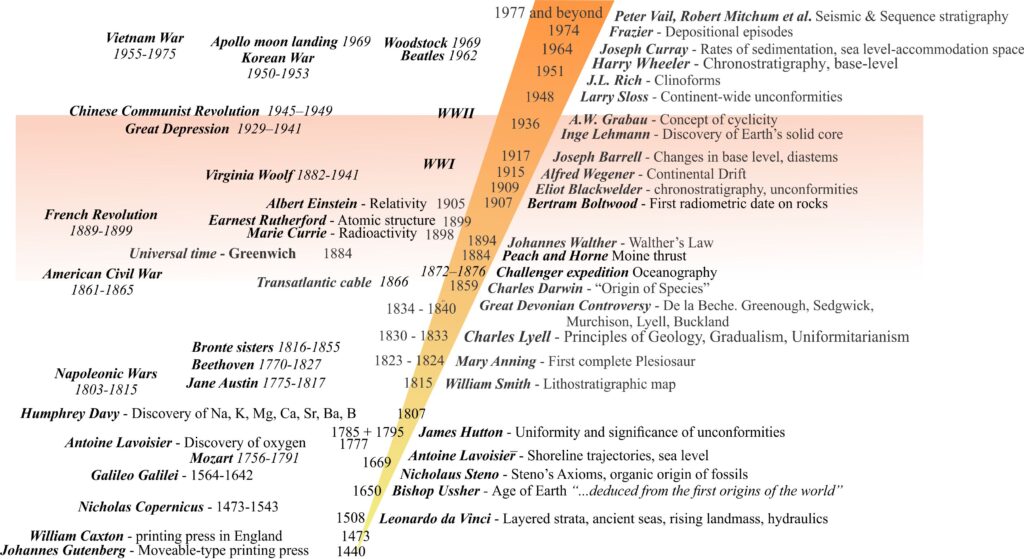

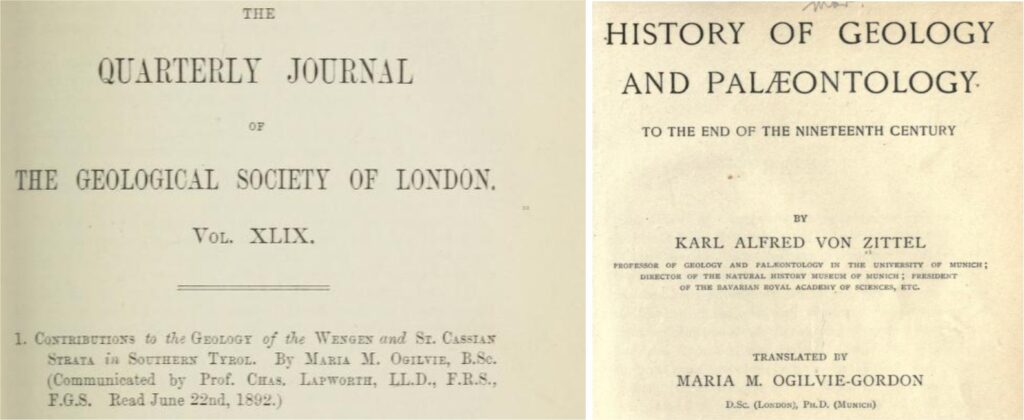

Whether by luck or good management she was invited that summer by Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen to accompany him on a five-week field excursion to the Dolomites in northern Italy. These few weeks of mapping, collection, and analysis in an area of known structural complexity was all the incentive she needed to pursue study in geology. Ogilvie had two field seasons in 1891 and 1892, putatively under the guidance of eminent paleontologist Karl von Zittel, although in her own words there was little or no actual supervision. By 1893 she had published papers (in German and English), including descriptions of various fossil groups like “Microscopic and systematic study of Madreporarian types of corals” (she had also studied modern corals).

One paper in particular, published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society (1893, London) resulted in her submitting a thesis with the same title to London University – Contributions to the Geology of the Wengen and St. Cassian Strata in Southern Tyrol” with that institution granting her a Doctor of Science – a first for women in United Kingdom. Notably, the paper was presented to the Geological Society in 1892, but it was read by Charles Lapworth because women were not permitted to attend these meetings.

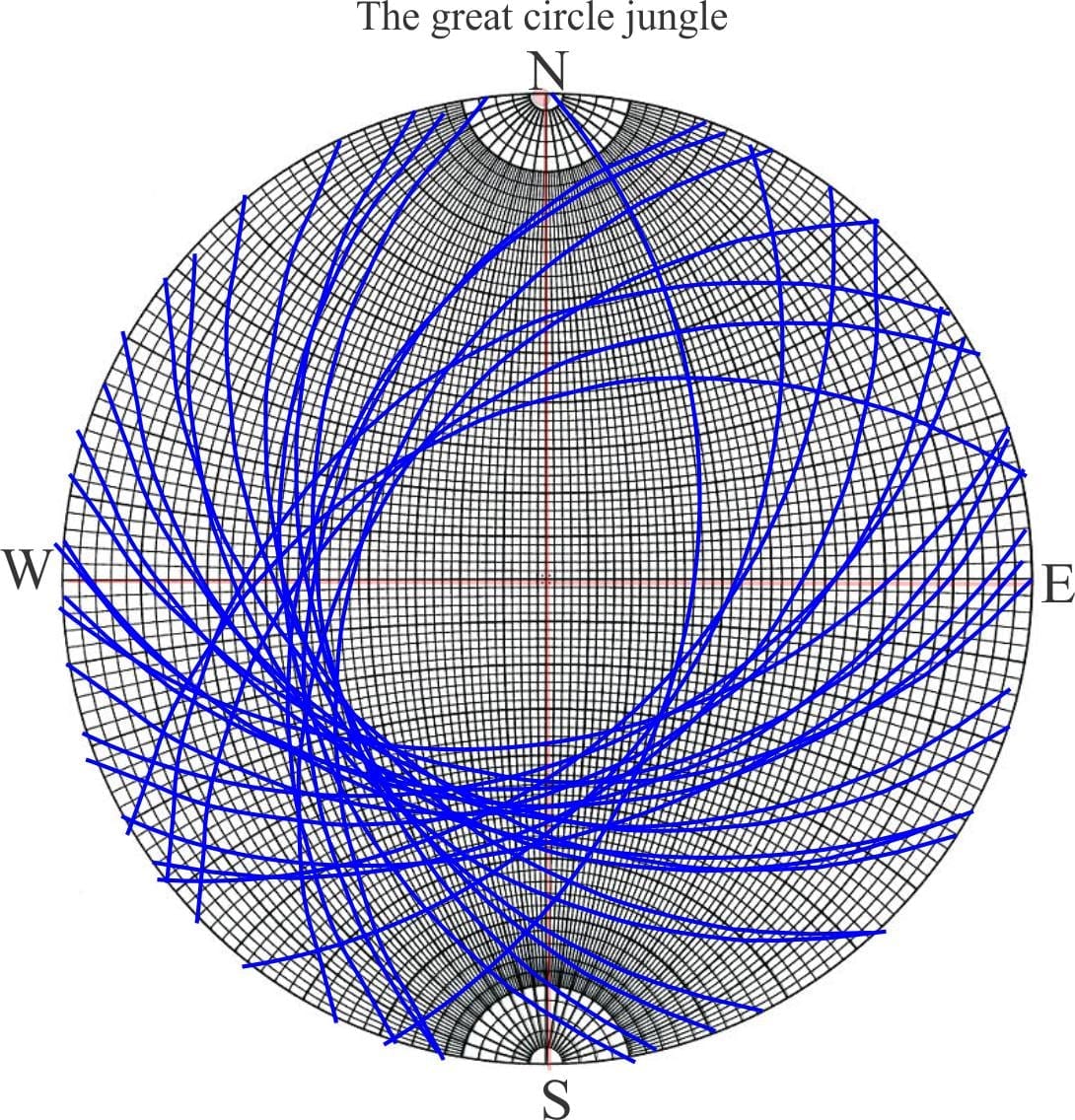

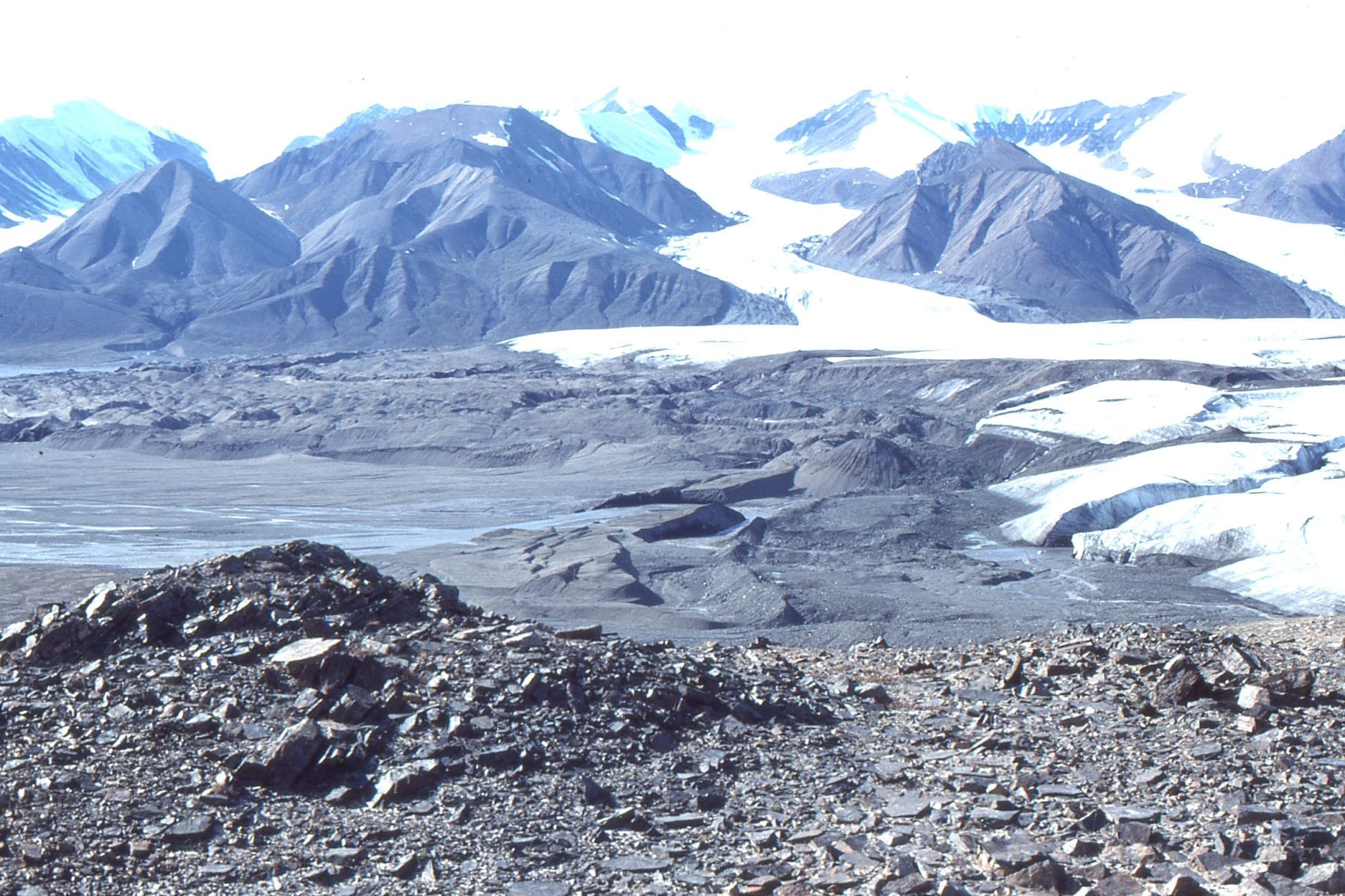

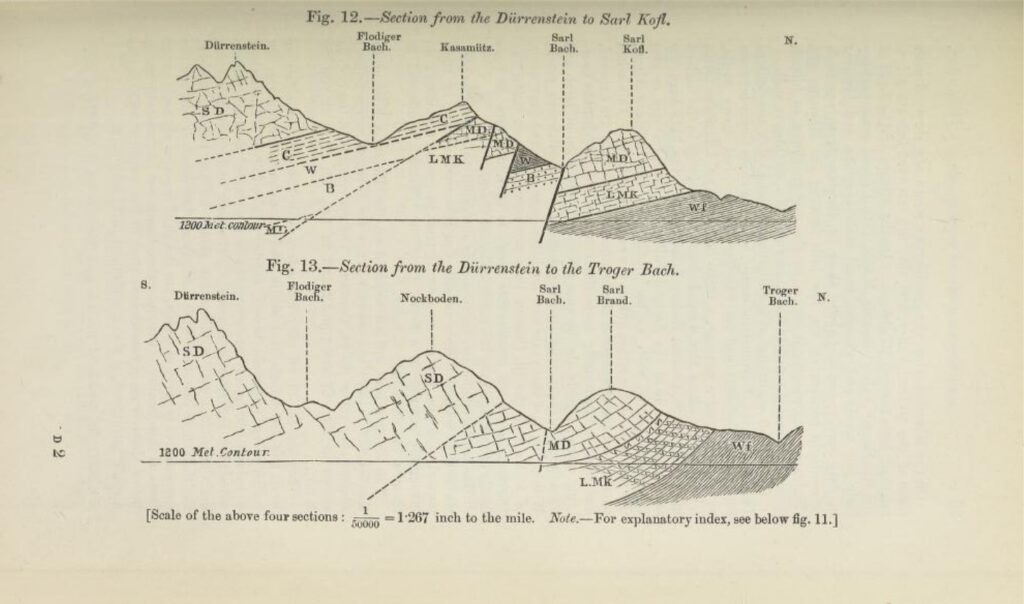

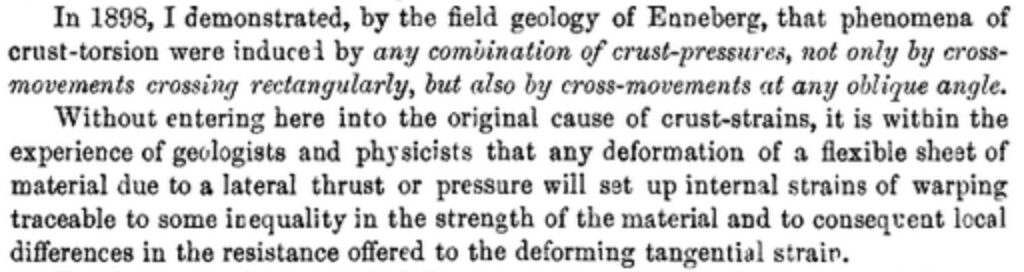

Ogilvie’s structural analysis of the Dolomites continued, encouraged by discussions with Archibald Geikie and Charles Lapworth. But I suspect that it was correspondence with Benjamin Peach and John Horne, the two Scottish geologists who had unraveled the mysteries of the Moine Thrust in the western Highlands, that triggered her own interpretations of thrust tectonics to explain Dolomite Mountain structures – identifying an early phase of folding and a later phase of thrust repetition. She published her new interpretation of Dolomite structural evolution in the Geographical Journal (of the Royal Geographical Society, volume 16, No. 4) in 1900 – The Origin of Land-Forms through Crust-Torsion. The sophistication of this interpretation is immediately apparent in her introductory statement about crustal flexure and fault deformation (p. 457):

Aware of the importance of Ogilvie’s discoveries, Munich University awarded her a PhD in 1900 – again she was the first woman to receive this honour from the university. As if this wasn’t enough, she had embarked on an English translation of von Zittel’s A History of Geology and Palaeontology, that she published in 1901.

Her marriage to John Gordon in 1895 and the ensuing family commitments proved no barrier to continuing geological field work, but she also became increasingly involved in local politics and groups involved in women’s rights, including being voted President of the National Council of Women of Great Britain and Ireland in 1916, and vice-chair of the International Council of Women, and in 1919 (post WWI) for the Representation of Women in the League of Nations (precursor to the United Nations).

Her latest publications included a 400 page treatise – The Groden, Fassa and Enneberg area in the South Tyrolean Dolomites published in 1927 by the Austrian Geological Survey. An earlier version of the manuscript had been lost in the aftermath of the war, requiring a complete rewrite of the text, its maps and illustrations (Wachtler and Burke, 2007). She also compiled a couple of popular field-guides to the geology of the Dolomites published in German and English in 1928.

Ogilvie-Gordon received several awards and recognition.

- She was included in the first group of eight women admitted as Fellows to the Geological Society in 1919 (C. Burek, 2009).

- In 1932 she was awarded the Lyell Medal by the Geological Society, the first woman to receive this award since its inception in 1876.

- An honorary Law Degree (LLD) from the University of Edinburgh in 1935.

- She was made a Dame Commander of the British Empire in 1935 in recognition of her scientific achievements and services to society.

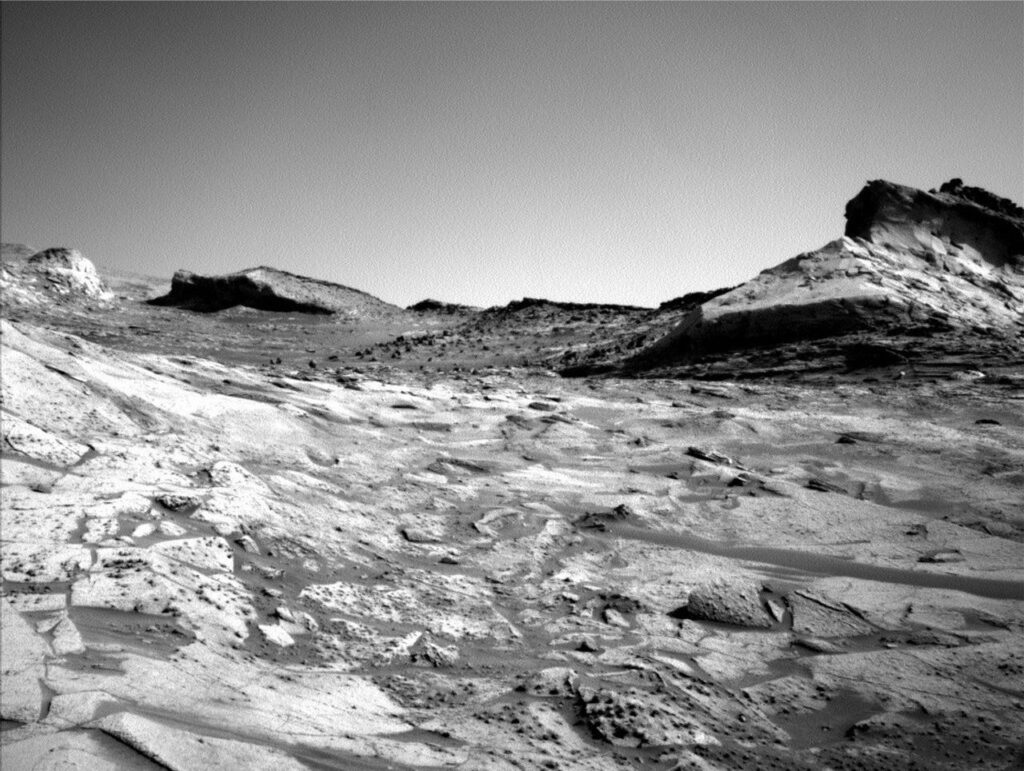

Recognition of her pioneering status continued in 2021, 82 years after her death, when the science team leading the Mars Curiosity Rover, named a pass on the west side of Mount Sharp (Gale Crater) the ‘Maria Gordon Notch’ (Michelle Minitti, August, 2021).

Image credit: Mars rover Curiosity on Sol 3222, NASA/JPL-Caltech

References and other documents

Cynthia Burek, 2005. Dame Maria Matilda Ogilvie Gordon, A Britisher and a woman at that (1864-1939). PDF.

Cynthia Burek, 2009. The first female Fellows and the status of women in the Geological Society of London.

Geological Society of London Blog; 100 years of female Fellows: Maria Matilda Gordon, 2019.

Michelle Minitti, 2021. Maria Gordon Notch. NASA Blogs.

Maria Ogilvie 1893. Contributions to the Geology of the Wengen and St. Cassian Strata in Southern Tyrol” Read by Charles Lapworth.

Maria Ogilvie, 1900. The Origin of Land-Forms through Crust-Torsion. Geographical Journal (of the royal Geographical Society, volume 16, No. 4)

Maria Ogilvie, 1901. translation of Zittel’s history of geology and paleontology

Maria Ogilvie Gordon, 1906. Microscopic and systematic study of Madreporarian types of corals”. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History, v. XVII

Maria Ogilvie Gordon, 1927. The Groden, Fassa and Enneberg area in the South Tyrolean Dolomites. Austrian Geological Survey.

Maria Ogilvie Gordon, 1928. Guide for Geological Tours in the South Tyrolean Dolomites.

Scientific American. Dame Maria Matilda Ogilvie Gordon: Pioneering geologist of the Dolomites

Scottish Geology Trust, Dame Maria Ogilvie Gordon 1864 – 1939.

M. Wachtler, and C.V. Burek, 2007. Maria Matilda Ogilvie Gordon (1864-1939): a Scottish researcher in the Alps. In BUREK, C. V. & HIGGS, B. (eds): The Role of Women in the History of Geology. Geological Society: 305-317.