This biography is part of the series Pioneering women in Earth Sciences – the link will take you to the main page.

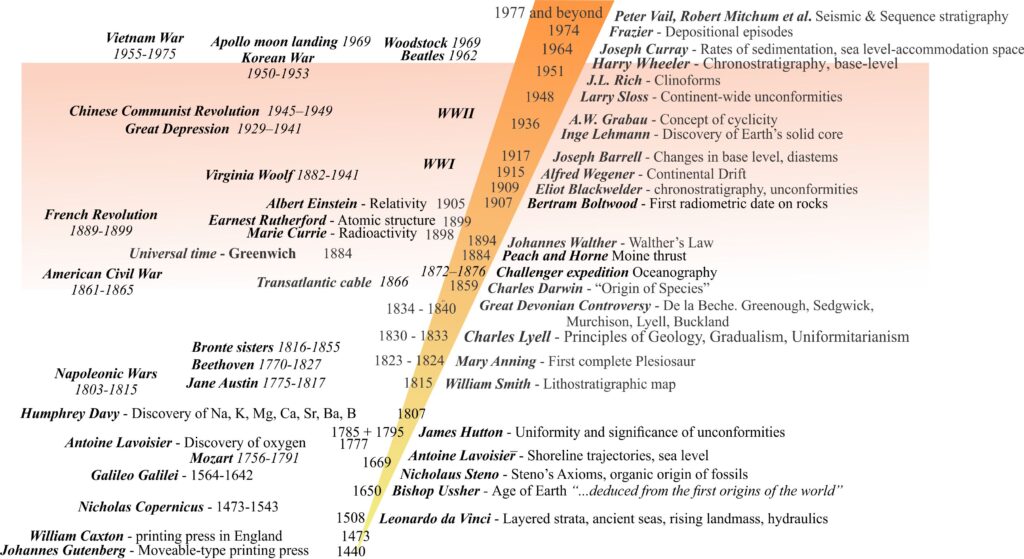

The concept of a stratigraphic column is a late 18th C to 19th C invention – it is one of the most important constructs in the history of the geological sciences. Stratigraphic columns display the order of rocks and geological time. The concept of relative time in geology began with Nicholas Steno’s propositions, recognizing that young rocks or strata overlie older rocks. Prior to the advent of radiometric dating in the early 20th C, the primary measures of relative age were fossils (this was the case even before Darwin’s proposals for evolution).

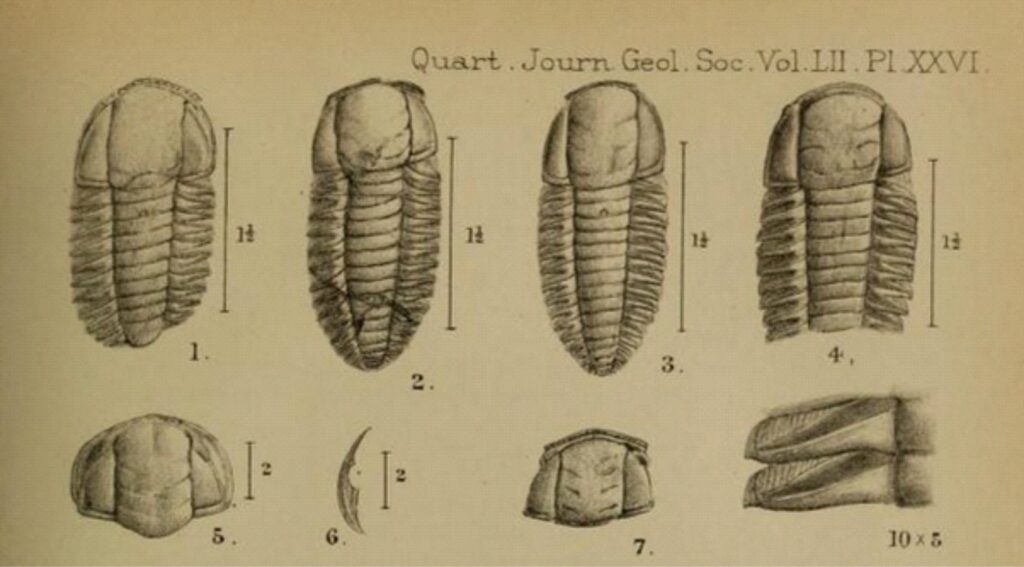

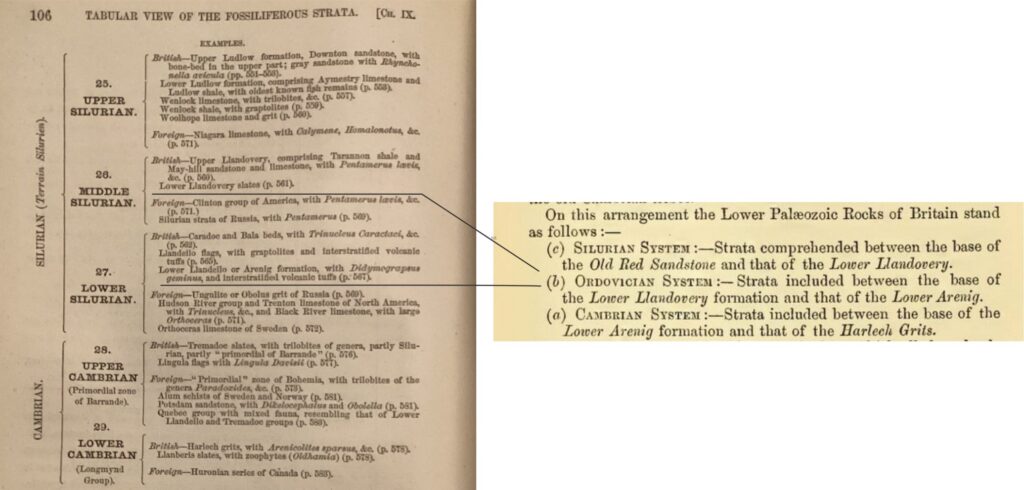

The task of dividing the stratigraphic column into the familiar time-based periods and rock-based systems (Cambrian, Devonian, Jurassic and so on) occupied the time and energy of many naturalists-geologists in the 19th C. In fact, the whole enterprise became highly competitive with public displays of jealousy and overblown egos (a great read is Martin Rudwick’s The Great Devonian Controversy). Defining the Lower Paleozoic Cambrian and Silurian periods proved to be particularly contentious, involving two well-known geologists – Adam Sedgwick and Sir Roderick Murchison. Their arguments commonly centred on the identification and utility of fossil assemblages, particularly trilobites and graptolites. The boundary between these two periods was problematic and wasn’t resolved until after their deaths; at this historical juncture Charles Lapworth in 1879 proposed a solution to the problem by adding a third period, the Ordovician between the Cambrian and Silurian. This stratigraphic ordering is in use today although it took several decades to become widely accepted. For example, Archibald Geikie in his 1927 edition of Class-Book of Geology, refers to the Cambrian-Silurian stratigraphy, omitting reference to the Ordovician.

This is where Margaret Crosfield and her colleagues Gertrude Elles, Ethel Shakespear, and Ethel Woods (nee Skeat) enter the picture. The work they did provided critical paleontological and stratigraphic confirmation of the boundary between the Silurian and Ordovician periods. At the time all four women (later nick-named the Newnham Quartet) were students at Newnham College, Cambridge (Burek and Malpas, 2007) but were persuaded by Professors Hughes and Marr (University of Cambridge) to engage with the Ordovician problem (Marr would later ‘read’ papers by all four women at Geological Society meetings in 1896 – the women were not permitted to do this themselves).

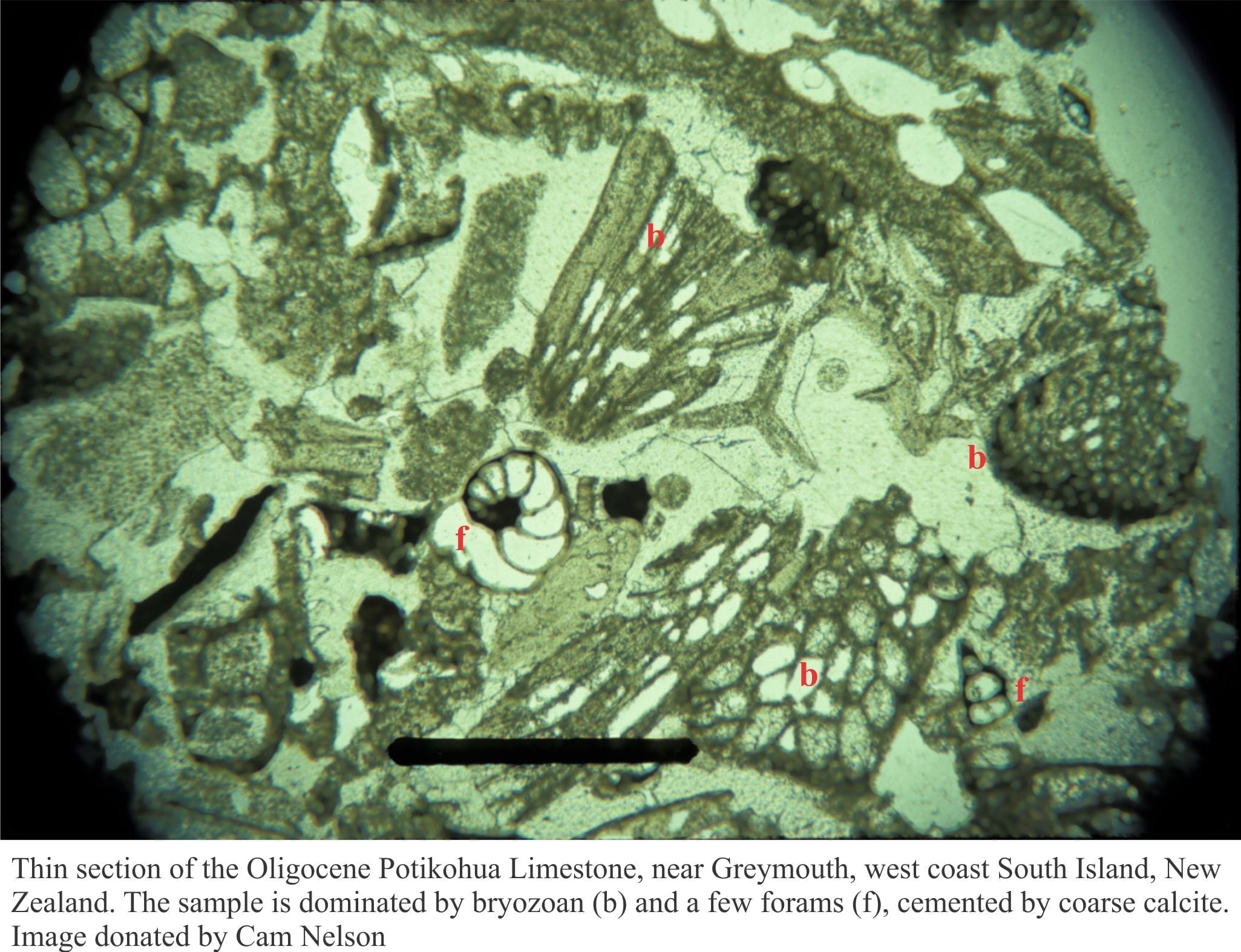

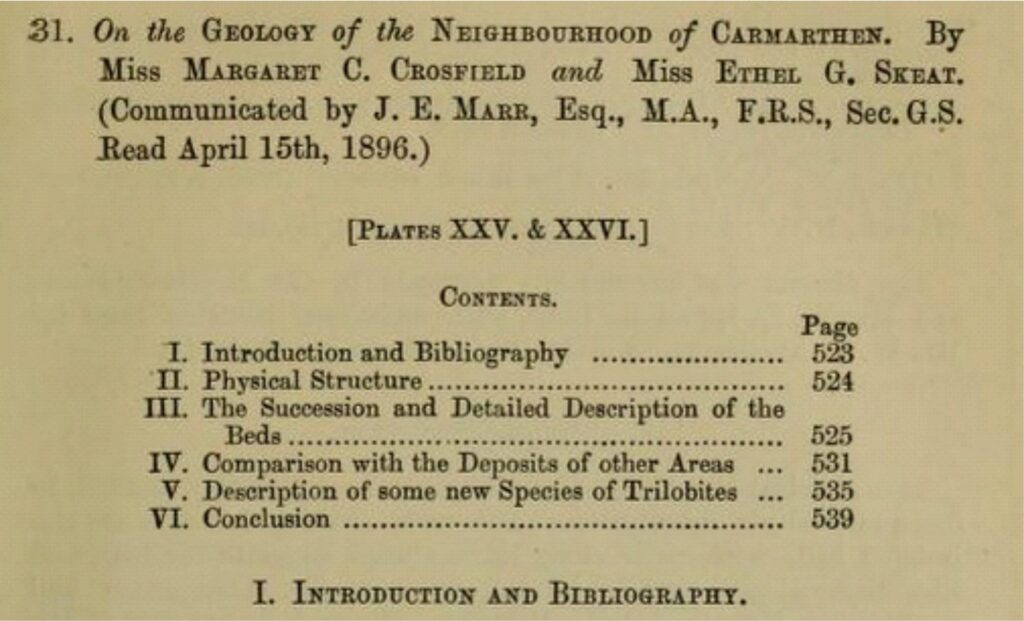

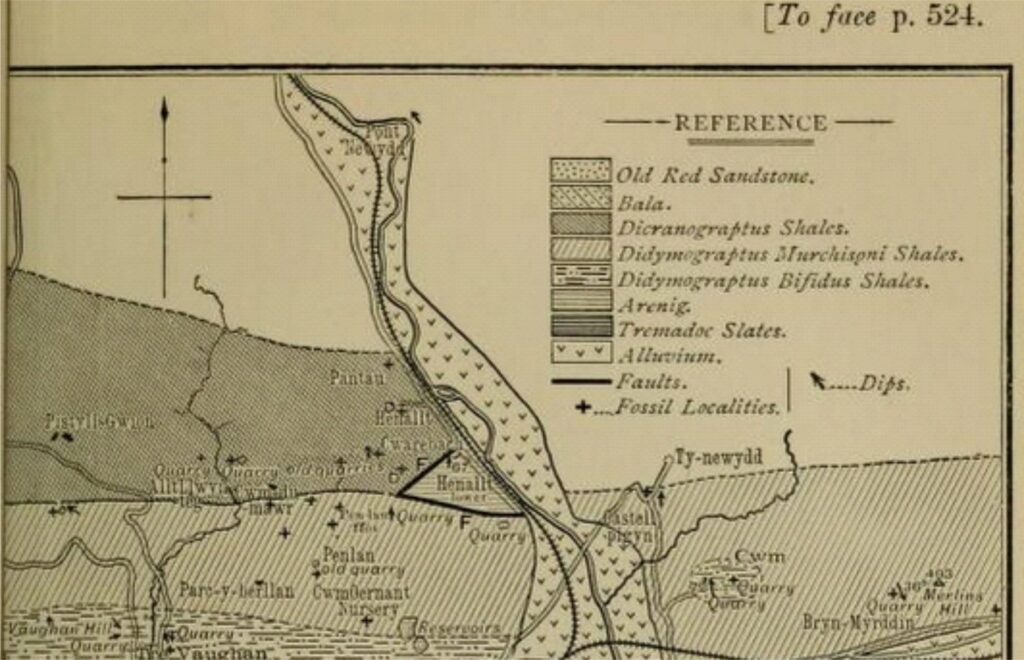

Margaret Crosfield’s contribution, with Ethel Woods was to map the Lower Paleozoic strata around Carmarthen in south Wales. The map they produced was of such high quality that it was later used by the British Geological Survey. Deciphering the stratigraphy required painstaking attention to detail in their rock descriptions, fossil collections and identifications. The principal fossil groups included trilobites and graptolites – for the latter group I expect there was plenty of discussion with Gertrude Elles who was becoming an acknowledged expert on graptolites. Crosfield and Woods also identified new species of trilobite. The Ordovician shales in this part of the world are thick and monotonous and teasing apart older from younger sections of rock required carful identification of the preserved fauna. The Crosfield – Woods paper outlining their investigations was read to the Geological Society in April 1896.

Margaret Crosfield went on to publish two more papers, another with Ethel Woods, and one with Mary Johnston. She led field trips under the auspices of the Geologist’s Association which she had joined in 1892, and gave numerous talks to various natural history groups (a full list of these contributions is given by C.V. Burek, 2020). Crosfield served on the Geologist’s Association Council in 1918 and was librarian for the Association from 1919-1923. In 1892 she was elected to the British Association for the Advancement of Science (established in 1831 – now referred to as the British Association), an organization that permitted membership of women equally with men (cf. the Geological Society). Crosfield was also a member of the Palaeontographical Society (established 1847) from about 1906 and served on its council. She was also very active in the Women’s Suffrage movement.

[The Palaeontographical Society (established 1847), Palaeontological Association (established in 1957), and the American Paleontological Society (established in 1908) are separate entities.]

Margaret Crosfield’s accession to Geological Society fellow

Margaret Crosfield, on the strength of her stratigraphic investigations, became the first woman elected as a Fellow to the Geological Society (of London), on May 21, 1919. Her journey, along with that of 7 colleagues also admitted as Fellows on that day, was circuitous and protracted. The Society had resisted the admission of women to its ranks for decades since its inception; women were not able to attend meetings or use the library. Some of the Society’s prominent Fellows were vociferously against women involvement – Adam Sedgwick for example is reported to have referred to women students as “nasty forward minxes” (J.W.Clark and T. McK. Hughes, 1890, p. 409). Papers could be submitted to the Society Proceedings or Quarterly Journal but were only published if sponsored by a male Fellow.

[The Geological Society was inaugurated on 13 November 1807 at a London pub – the Freemasons Tavern in Covent Garden]

Several motions were proposed between 1890 and 1919 that might have advanced female membership, but all were defeated; for example, adding the pronoun “her” to the Society bylaws in 1893. Several women did succeed in winning special financial grants like the Lyell Fund, Crosfield and paleontologist Gertrude Elles among them. But a motion to allow these women to collect their awards in person was also rejected.

Enter Archibald Geikie (1835-1924) – literally. Geikie was a prominent geologist who also served twice as President of the Geological Society, was a Fellow of the Royal Society, President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and Director of the British Geological Survey. Geikie was also involved in the debate about the existence of the Moine Thrust, initially disagreeing with Peach and Horne’s theory, but eventually recognizing the veracity of their evidence. Geikie generally supported the roles women played in scientific investigations, including roles in the Geological Society (C. Burek, 2018). He settled the issue of women’s attendance at meetings on March 20, 1901, by simply walking into the meeting accompanied by two ladies.

However, the Society’s position on fellowship remained doggedly stubborn. At one stage in this seemingly intractable problem, they resorted to an arcane rule of law (presented by Richard Haldane, 1902) wherein women who were married were no longer considered separate individuals. This meant that only single women could be admitted (The Geological Society).

The Society’s stubbornly long-arm was finally twisted on March 26, 1919. In 1918, the post-war British parliament acted to grant women aged 30 and over the right to vote. The Sex Disqualification Removal Act was also passed in 1919. The Society in effect had no legal recourse to refuse women full participation rights. This included the right to submit and read papers themselves at meetings, and the accession to fellowship.

On May 21, 1919, 8 women were elevated as Fellows (Megan O’Donnell , 2019):

- Margaret Chorley Crosfield (1859-1952) – officially the first.

- Gertrude Lilian Elles (1872-1960)

- Mary Sophia Johnston (1875-1955)

- Rachel Workman MacRobert (1884-1954)

- Maria Matilda Gordon (1864-1939)

- Ethel Woods (1865-1939)

- Jane Donald Longstaff (1855-1935)

The following year (1920) Eleanor Reid (FGS), a paleobotanist, became the first woman to read her own papers at a Geological Society meeting.

References and other documents

Charles Lyell, 1868. Elements of Geology. 6th Edition, New York, D. Appleton & Co.

Charles Lapworth, 1879. On the tripartite classification of the Lower Palaeozoic rocks. Geological Magazine, 6, 1–15. Internet Archive

J.W. Clark and T. McK. Hughes, 1890. The Reverend Adam Sedgwick. Volume II. The Cambridge University Press. Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Margaret C. Crosfield and Miss Ethel G. Skeat, 1896. On the Geology of the Neighbourhood of Carmarthen: (Communicated by J. E. Marr, Esq., M.A., F.R.S., Sec.G.S. Read April 15th, 1896.)

Crosfield, M.C. & Johnston, M, 1914. A study of Ballstone and the associated beds in the Wenlock Limestone of Shropshire. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 25, 193-226

Ethel Gertrude Woods, and Margaret Chorley Crosfield.1925. The Silurian Rocks of the Central Part of the Clwydian Range. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, Volume 81, p. 170 – 194

Geikie, Archibald, 1927. Class-Book of Geology. 6th Edition. Macmillan & Co, Ltd. London.

Exploring Surry’s Past: Margaret Chorley Crosfield (1859-1952): Suffragist, Geologist and Quaker of Reigate.

Cynthia V Burek and Jacqui A Malpas, 2007. Rediscovering and conserving the Lower Palaeozoic ‘treasures’ of Ethel Woods (nee Skeat) and Margaret Crosfield in northeast Wales. Geological Society London Special Publication, p. 205–221.

Cynthia V Burek, 2009. ‘The first female Fellows and the status of women in the Geological Society of London’, Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 317, 373-407.

Cynthia V. Burek, 2014. The contribution of women to Welsh geological research and education up to 1920, Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, Volume 125, Issue 4, p. 480-492.

Ferwen, 2016: Forgotten women of Paleontology: The Newnham quartet. Letters from Gondwana.

Cynthia V. Burek, 2018. Archibald Geikie: His influence on and support for the roles of female geologists. Geological Society Special Publication 480, Chapter 4.

Megan O’Donnell , 2019. 100 years of female Fellows: Margaret Crosfield. The Geological Society Blog.

C.V. Burek, 2021. Margaret Chorley Crosfield, FGS: the very first female Fellow of the Geological Society: Geological Society Special Publication, 506. Chapter 4.