Fossils and Strata; Relative geological time

When one sedimentary layer overlies another, we can be fairly certain that the lowermost is the older of the two. The important step of codifying this relationship in a set of rules was taken up by Nicholas Steno in 1669 (the Law of Superposition). Although fairly obvious now, this was an important intellectual step in understanding what we now call relative time; that things, especially sedimentary strata, are older or younger than other strata. This is the essence of the science we call stratigraphy.

Jumping ahead to 1815 and the publication of William Smith’s geological map of England, Wales and part of Scotland. This map was a real breakthrough. Simon Winchester’s ‘The Map That Changed The World’ (Viking 2001) is a great account not only of Smith himself, but of the vagaries of social class and bigotry that he had to deal with. Smith’s map depicts the order of strata.

William Smith recognized the distinctiveness of certain kinds of rock like limestone, chalk and coal and traced (mapped) these across the countryside. Other rock types like mudstones are less distinctive and more difficult to place in terms of their relative age. Smith solved this problem with fossils.  He found that certain kinds or groups of fossils were restricted to certain strata, and that the kinds of fossils changed from older to younger rocks. The change in fossil types was not random, but repeatable in strata from one area to another. Smith realized that the presence of certain fossils in a particular set of strata allowed him to predict its position relative to older or younger strata in other areas; in other words, Smith was able to correlate one set of strata with another set, based on the presence of specific fossils or groups of fossils. William Smith had discovered the value of Biostratigraphy – the stratigraphy of fossils.

He found that certain kinds or groups of fossils were restricted to certain strata, and that the kinds of fossils changed from older to younger rocks. The change in fossil types was not random, but repeatable in strata from one area to another. Smith realized that the presence of certain fossils in a particular set of strata allowed him to predict its position relative to older or younger strata in other areas; in other words, Smith was able to correlate one set of strata with another set, based on the presence of specific fossils or groups of fossils. William Smith had discovered the value of Biostratigraphy – the stratigraphy of fossils.

The science of biostratigraphy has advanced by leaps and bounds. Smith had no idea why one kind of fossil changed to another. It was another 44 years before Charles Darwin published a theoretical basis for the evolution of species. Fossils were also central to the debates, controversies and arguments that arose when major geological periods like the Devonian were first identified (in Devonshire, southern England). Today, fossils and biostratigraphy are cornerstones of the earth sciences.

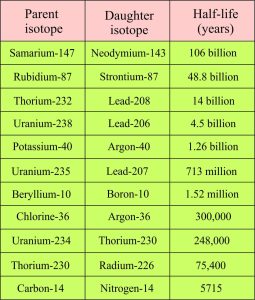

The most useful kind of fossils for correlation of relative time are those whose species evolved rapidly, were widespread (cosmopolitan) and are preserved in abundance. For example, in the Jurassic period, ammonites (which were free swimming) are used extensively to define specific times zones. Because they tend to be cosmopolitan they can be used to correlate strata over wide areas, even between continents.

Fossils provided the critical information to identify relative time long before radiometric dating had been discovered. Fossils in and of themselves do not give us a geological date in years. To measure time in a quantitative way we turn to radiometric dating.

Atoms, Isotopes and Decay

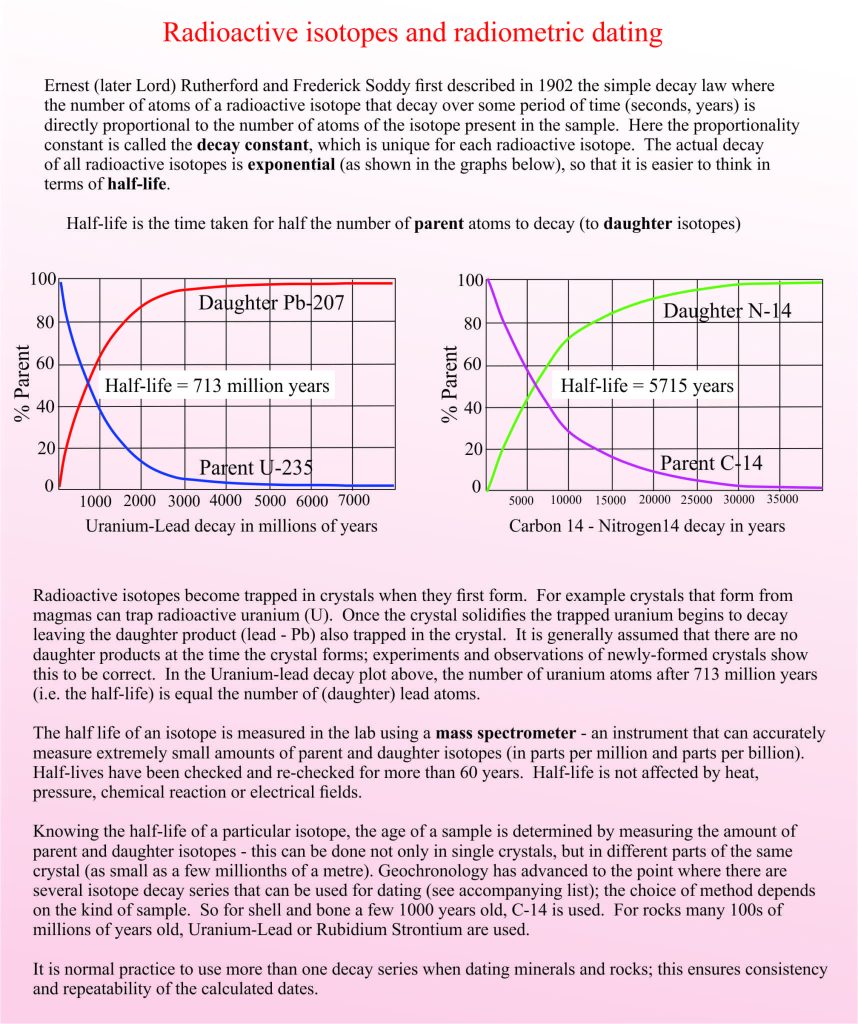

The science and technology of radiometric dating of minerals and rocks did not begin to develop for another 100 years following publication of William Smith’s map (the accompanying diagram explains the basic theory of radiometric dating). A little more than a decade after Becquerel’s discovery of radioactivity in uranium (1896), Bertram Boltwood at Yale University published (1907) the geological ages of 26 rock samples using the decay of radium. Although ther

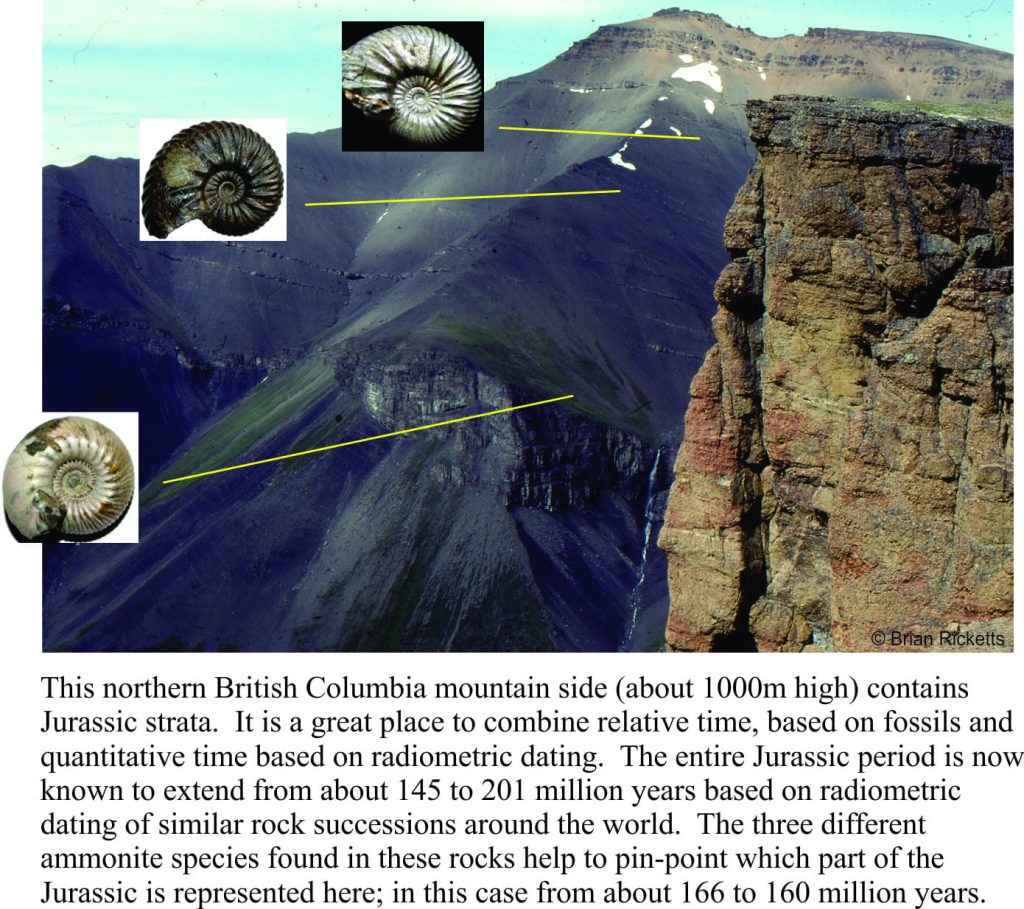

The science and technology of radiometric dating of minerals and rocks did not begin to develop for another 100 years following publication of William Smith’s map (the accompanying diagram explains the basic theory of radiometric dating). A little more than a decade after Becquerel’s discovery of radioactivity in uranium (1896), Bertram Boltwood at Yale University published (1907) the geological ages of 26 rock samples using the decay of radium. Although ther e were errors in his results because of experimental determination of the isotopes and poorly known radium half-life, the method provided the impetus for more sophisticated dating by Arthur Holmes (Imperial College) using the uranium-lead decay series (the most common radioactive isotopes used in dating and each half life are listed opposite). Arthur Holmes is widely regarded as the pioneer of isotope dating methods, or geochronology; his first published date in 1911 was 370 million years for a Devonian rock.

e were errors in his results because of experimental determination of the isotopes and poorly known radium half-life, the method provided the impetus for more sophisticated dating by Arthur Holmes (Imperial College) using the uranium-lead decay series (the most common radioactive isotopes used in dating and each half life are listed opposite). Arthur Holmes is widely regarded as the pioneer of isotope dating methods, or geochronology; his first published date in 1911 was 370 million years for a Devonian rock.

Holmes and his colleagues had their detractors, particularly those diehards who still agreed with Kelvin’s determination of the age of the earth (based on cooling) at less than 100 million years. But like all good science, it withstood the tests of criticism, bias and shear pigheadedness.

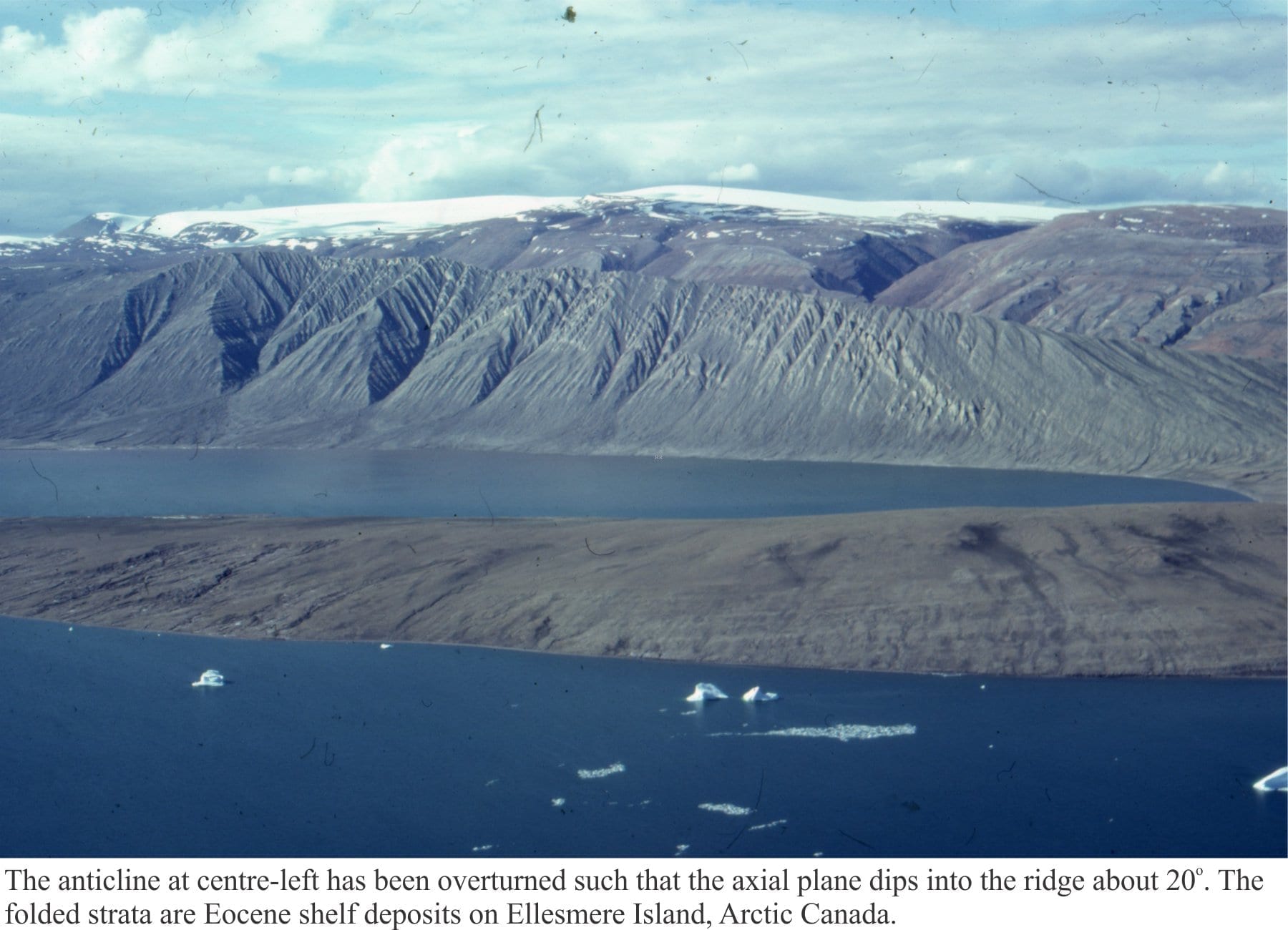

The early geochronology successes did two things: they provided actual dates for rocks and therefore geological events (this in itself was exciting enough), and they began the process of marrying the dates with geological periods that, until then represented relative time. Geologists could now see a way to quantify not only the age limits of periods like the Devonian or Jurassic but also time divisions within. Radiometric dating has now advanced to the point where geologists can fine-tune geological periods and geological events. We can accomplish this by looking for strata that not only contain the important fossils, but also contain layers of volcanic ash or other products of volcanism such as lava flows. The volcanic deposits commonly contain minerals that will provide a radiometric date.

Just married; fossils and isotopes

The concept of relative time in stratigraphy developed independently of the science that gave rise to radiometric dating, although adherents of both were probably asking the same question – ‘how old is this rock?’. It is important to keep this level of independence in mind because today strata (with and without fossils) are not only referred to as (say) Jurassic, but are also quoted as being so many millions of years old. It is a scientific journey that has so far paid huge dividends. From William Smith’s map to paleontological excursions and laboratory experiments, geologists, chemists and physicists have forged a system of geological time that marries the relative with the quantitative.

3 thoughts on “Marrying Fossils, Isotopes and Geological time”

Pingback: my blog

Blue Host – they have an agreement of sorts with WordPress

Pingback: Free Piano