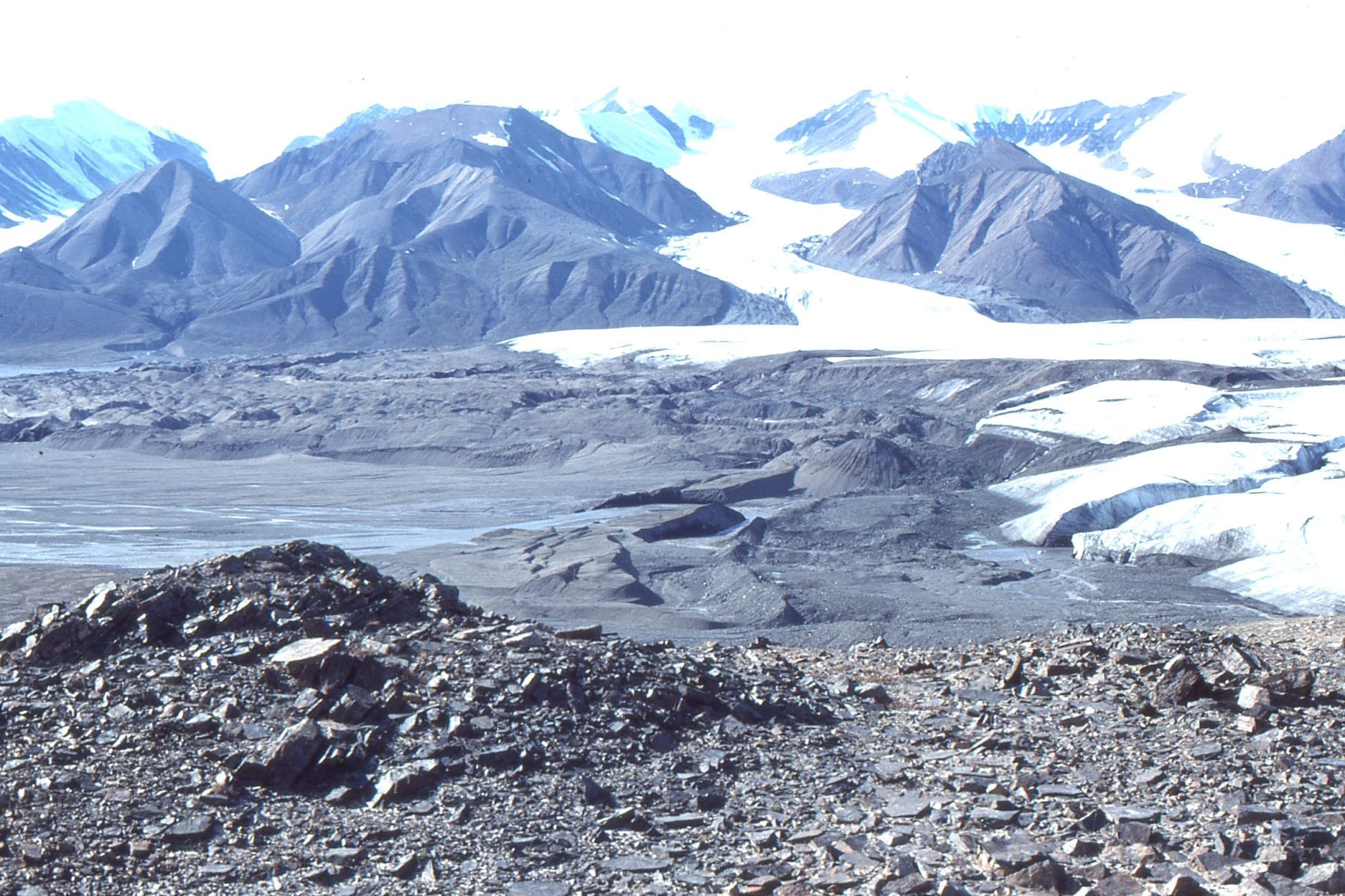

Morning tea in Murchison, a small rural town in northwest South Island (NZ), was rudely interrupted on June 17, 1929, by a 7.3 magnitude earthquake (Ms 7.8). Shaking was recorded over much of the country. There were 17 deaths and most of those were the result of people caught by landslides; estimates of up to 10,000 landslides were triggered in the mountainous terrain by the event. The region was sparsely populated at the time (not much has changed). The earthquake focal depth was about 20 km and located on White Creek Fault that is now recognized as part of the Marlborough fault system that splays northward from the Alpine Fault – the lithosphere-scale transform fault that separates the Pacific Plate (east) from the Australian Plate. Displacement on White Creek fault was up to 4.5 vertical metres and 2.5 m laterally.

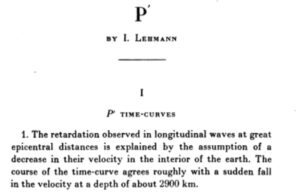

Although the Murchison earthquake may have been of passing interest to the rest of the world, to Inge Lehmann the seismic records of the event cemented her ideas about the deep structure of Earth. She published her theoretical considerations in 1936 – in a paper with the singularly brief title “P”.

Lehmann enrolled at Copenhagen University at age 19 (1907), focusing on mathematics with sides of physics, chemistry, and astronomy. In 1910 she transferred to Newnham College ((the women’s college at Cambridge University – of Newnham Quartet fame). Her experience there was very different to her Danish university life that allowed women to participate in most educational activities. Cambridge University at that time barely tolerated a women’s presence; Cambridge didn’t grant women degrees until 1948. She returned to Copenhagen and after a period of illness earned her degree 1920.

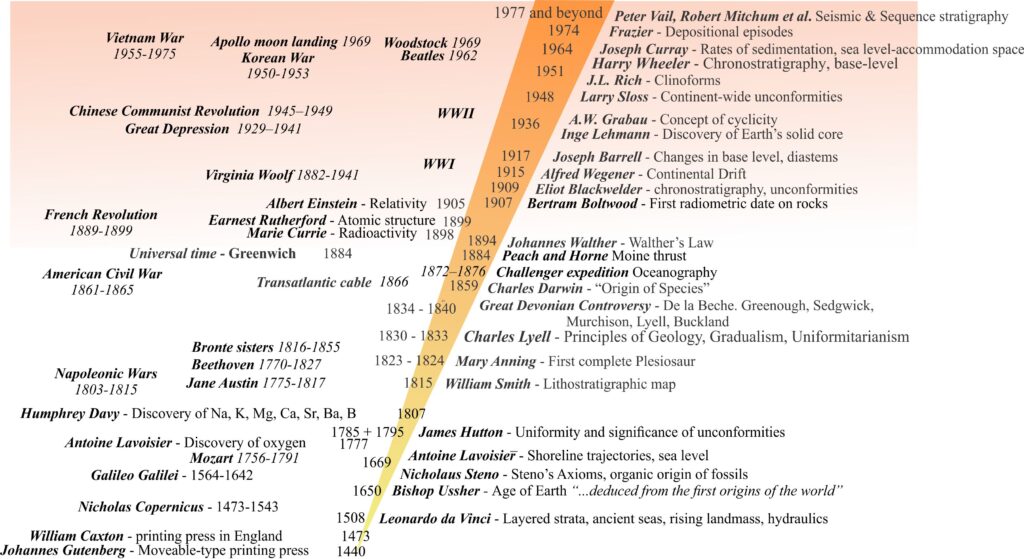

In 1925 Lehmann became an assistant at the Danish Geodetic Institute where her interest in seismology and the installation and interpretation of data from the newly developed seismographs was encouraged (seismographs or seismometers are the instruments that record arrival of earthquake energy pulses, or waves; seismograms are the paper or digital records of these events). By the early 1930s she had become a central figure in international seismology, attending and presenting at conference meetings in 1931 (Centenary of the British Association), in 1936 the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics, and again the British Association in 1938.

The science of seismology advanced rapidly during the early 20th C and with it a deeper understanding of Earth’s inner structure. In 1897 the British seismologist Richard Oldham deciphered two fundamentally different kinds of signal from seismograph records, now referred to as Body waves that travel through Earth’s interior, and Surface waves that are bound to Earth’s surface. All wave types are of value for deciphering Earth’s structure, but body waves are the primary tool used to locate earthquake epicentres and focal depths, and for unraveling the deepest structures within Earth. Oldham also identified two types of body wave:

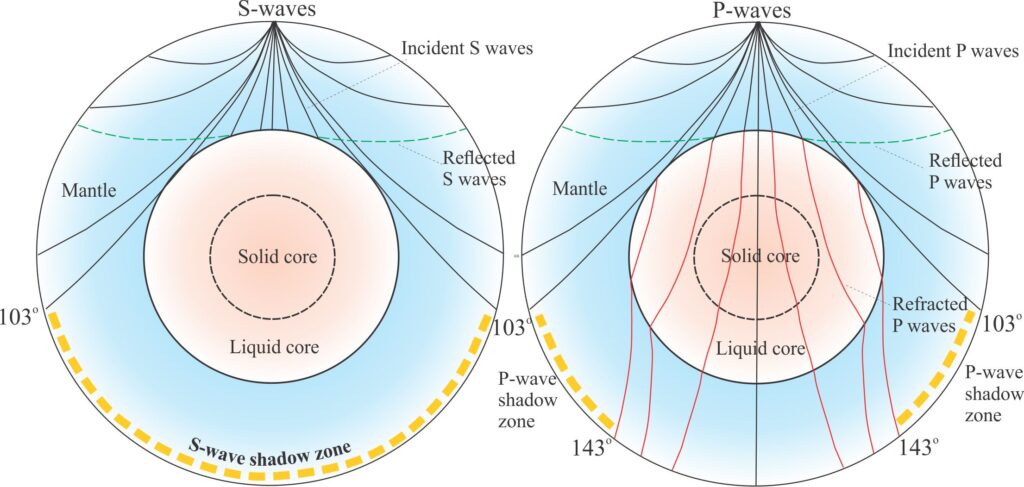

- P Waves that are compressional, also called pressure waves. P waves oscillate back and forth as they travel through the Earth. Particles (e.g., rock) will move in the same direction as wave propagation. P waves are transmitted through rock and fluid. They are generally the fastest waves and the first arrivals at seismic stations.

- S Waves, or shear waves where particles move at right angles to the direction of wave propagation (i.e. sideways). S waves are NOT transmitted through fluids.

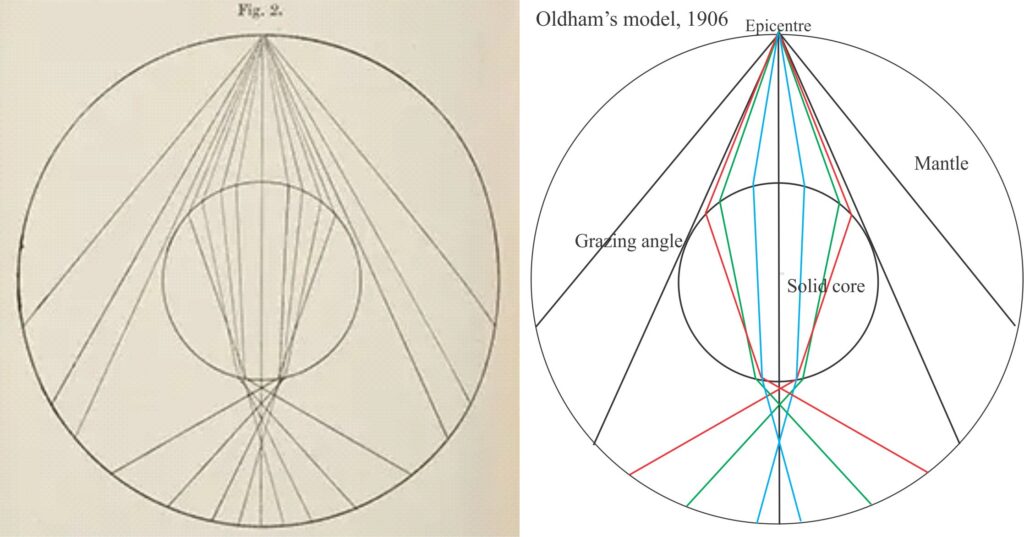

Prior to the end of the 19th C the solid Earth was generally considered to be a relatively homogeneous, spherical, rocky mass. The first to challenge this, based on seismology data (that were at a nascent stage of development at that time) was Emil Weichert in 1897 who proposed that Earth consisted of a solid metallic core and a rocky mantle. In 1906 Oldham demonstrated a fundamental discontinuity at depth, based on the change in velocity of P waves. He concluded that Earth had a metallic core of different density to its outer rocky mantle and that the depth to the boundary was about 3000 km. In 1912 Beno Gutenberg (a student of Wiechert) estimated the discontinuity at 2900 km, based on P and S wave travel times (very close to Oldham’s estimate); now known as the Gutenberg Discontinuity. However, the consensus maintained a solid core, and a wholly solid Earth. British seismologist Harold Jeffreys in 1926 upset the status quo, identifying an S wave shadow zone at the discontinuity and concluded that the core was in fact a dense metallic liquid (S waves do not transmit through liquids).

[Seismic discontinuities occur where there is a change in rock density (also called acoustic impedance), or where there is a change in state, for example from solid to liquid]

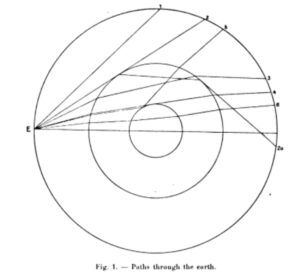

[Reflected waves ‘bounce’ off discontinuities within Earth at an angle equal to their incident angle. Refracted waves pass through a discontinuity at an angle greater or less than the incident angle depending on the density contrast across the discontinuity. There is also a change in seismic velocity in refracted waves. Every time a wave is reflected or refracted there is energy loss.]

These early 20th C developments were the backdrop to Inge Lehmann’s creativity and discovery. Her 1930 report on the Murchison event was an early attempt to unravel the tangled seismogram webs that contained signals from primary P and S waves, plus their reflected and refracted waves. In the report she identified signals from four seismograph stations that were almost antipodal to the Earthquake epicentre: Ivigtut (southwest Greenland), Abisco (Sweden), Scoresby-Sound (east Greenland), and Pulkovo (Russia).

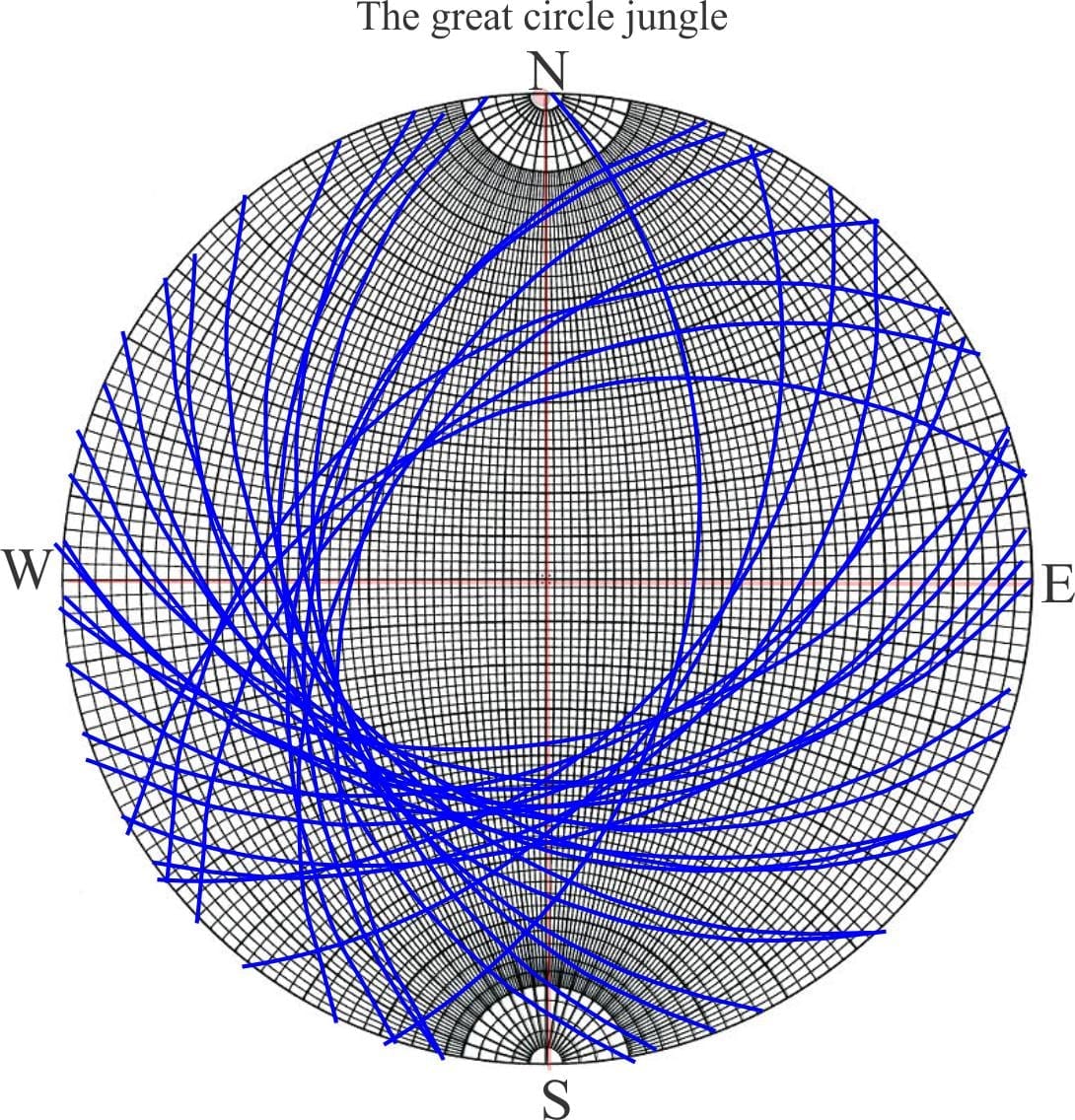

The ‘distance’ from a seismic receiver to the earthquake epicentre is usually quoted as an angular measure, an arc formed by two radii from Earth’s centre that describe the angle between a great circle through the seismic station receiver and the another through the epicentre. Four of the antipodal stations Lehmann worked with have angles of about 150o (not quite antipodal but as close as she was going to get with the available data). Antipodal ray paths are important because they must pass close to the centre of Earth. The four stations were pivotal to her developing theoretical considerations.

Seismic waves that ‘graze’ a discontinuity will be mostly reflected. Those that pass through a discontinuity will be reflected and refracted. Because the four stations identified by Lehmann were antipodal, P and S waves would be reflected and refracted at high angles, close to the centre of the Earth. Both P and S waves have shadow zones that should be devoid of signals (because of the geometries of reflection and refraction, as shown in the diagram above). Based on Jeffreys discovery of a liquid core, she surmised that refracted P waves should be retarded (have lower seismic velocities) while passing through the core until they emerged on the other side (150o away), at which point their velocity should increase. P waves that arrived at the four antipodal stations indicated passage through the core but had energies (wave amplitude and shape) different to what she expected based on a wholly liquid core. In addition, seismic stations elsewhere in Europe and Russia (then Soviet Union) also received weak P-wave signals, but these stations were located in the P-wave shadow zone (between about 103o – 143o), for example Baku (Azerbaijan) 137.4o, Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg, Ural Mountains) 135o, Irkutsk (Siberia) 110.8o. Furthermore, these P waves were delayed beyond time values predicted by the liquid core model. The only way she could explain these results was to hypothesize an inner, solid metallic core having a density greater than the liquid metallic outer core that reflected the P waves. She estimated the inner core radius at 1400 km. Hers was the first indication that the core was more complicated than first thought.

The interminable wait for recognition

The 3-4 years following her 1936 discovery saw fellow seismologists like Jeffreys, and Gutenberg and Richter provide additional confirmation of her two-shell core model. Gutenberg and Richter calculated the inner core velocity at 11.2 km.s-1 and a radius of 1200 km; current values range from 11.02 to 11.26 km.s-1.

Lehmann continued to work tirelessly, refining methods for locating epicentres and wave paths, adding a further discovery to her list – a discontinuity at about 220 km depth where both P- and S-wave velocities increase abruptly (this boundary and the inner core boundary are both referred to as Lehmann discontinuities which is a bit confusing). She also cofounded the Danish Geophysical Society in 1936.

Like most women scientists in the first half of 20th C, recognition of Inge Lehmann’s brilliance occurred at glacial pace, in keeping with the lack of enthusiasm that many scientific societies and universities had for inclusive membership. Lehmann had to wait until well after her retirement in 1953 (age 65) for awards like the Emil Wiechert Medal (1964, German Geophysical Society), Danish Royal Society Gold Medal (1965), election as a Fellow of the Royal Society (1969), and a medal from the Seismological Society of America in 1977 (age 89). She was the first woman to be awarded the William Bowie Medal in 1971 (American Geophysical Union). Lehmann also had honorary doctorates from two universities. Perhaps all these societies had just woken up to her presence, although the cynic in me suggests that they needed to get the awards out of the way before she died.

References and other links

Richard Dixon Oldham, 1906. The Constitution of the Interior of the Earth, as Revealed by Earthquakes. Geological Survey of India, Memoir V. XXIX.

Lehmann, I. 1930. P’ as read from the records of the earthquake of June 16th, 1929. Gerl. Beitr. Geoph., 26.

Lehmann, I. (1936). P’. Bureau Central Seismologique International, Traveaux Scientifiques (A), 14-88.

Bolt, Bruce A. and Hjortenberg, Erik, 1994, Memorial essay Inge Lehmann (1888–1993): Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, v. 84, pp. 229-233.

Martina Kölbl-Ebert, 2001. Inge Lehmann’s paper: “ P’” (1936). Episodes, v. 24. Classic Papers.

Erik Hjortenberg, 2009. Inge Lehmann’s work materials and seismological epistolary archive. ANNALS OF GEOPHYSICS, VOL. 52, N. 6.

Marie Dyekjær Eriksen, 2014 – 2015. Several articles grouped as ‘Inge Lehmann; The Woman who Discovered Earth’s Core’. Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen.

William B. Ashworth, 2018. Scientist of the Day: Richard Oldham. Linda Hall Library.