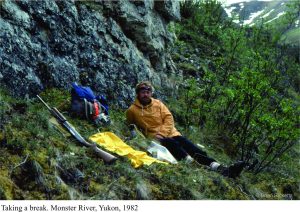

The best field projects are those that last several seasons; the ones you kind of own or share with any number of co-conspirators. These are the projects for which there can be scientifically productive tangents, and where there is usually regional or universal context. Then there are those odd, short-term projects that, at the time, seem a bit ad hoc but still present the opportunity for good science, and new adventures; 1982 was such a season. I was tasked with sorting out a group of sedimentary rocks in west Yukon, a hop, skip and a jump from the Alaskan border. This was the first and last time I worked in an area with substantial bush cover. The best exposure was on ridges above the tree-line, but to get from one ridge to another required crashing through northern boreal forest and the odd, insect-infested swamp. The black flies, deer flies, mosquitos and no-see-ums were something else.

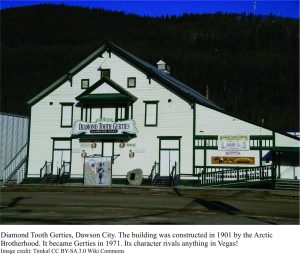

Our staging site was Dawson City (more like a small town), at the confluence of Yukon River and Klondike River. In 1896, the discovery of gold turned this sleepy northern village into a bustling, 30,000 strong hive of miners, tinkers, tailors, and some older professions of more dubious repute. I guess it seemed ‘city’ like back then. This was the Klondike Gold Rush, a wild but brief affair that produced rags and riches (a bit like modern Bull Markets). It was also the capital of Yukon until 1952. Modern Dawson City (population about 1400) makes good use of this boisterous past, epitomised by Diamond Tooth Gerties, Canada’s first casino that also boasts a floor show to rival Les Follies, and adult libations.

Dawson City is located a couple of degrees latitude south of the Arctic Circle. At the height of summer, the sun is only marginally below the horizon, and to celebrate the twilight, there is an annual Midnight Dome Race, a 7.2km run that climbs 564m (retiring afterwards to the Casino). Some of my colleagues would time their arrival or departure from Dawson City to compete.

Back to work.

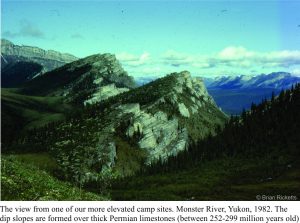

Most of our camps were along Monster River, that coursed through the map area. This also meant bush. More than one attempt to land the helicopter on the gravel river bars resulted in the trimming of some small trees. We did have a few camps on higher ground, but only when good water was not too far off. One particularly nice saddle overlooked some spectacular, rugged dip-slopes. There were also animal tracks, one of which went straight through our tent – something we discovered one evening when, my assistant Phil, who was sitting on a rocky outlook and playing his harmonica, suggested that I get the gun. Not 20m from the tent was a magnificent Grey Wolf (also known as a Yukon Wolf) – it could have been less than 20m; whatever, it seemed damn close and was in clear view. It also seemed very big. Beautiful coat. Just staring. After who knows how long, it slowly turned and walked back down the trail. No worries. Perhaps I didn’t look appetizing. It was my first encounter with these graceful animals (a couple of years later I encountered some Arctic Wolves, but they were very shy and scrawny).

Despite the need for bush-whacking, camps along the river were best; water at the door step, and a (cool) dip at the end of the day. We were mindful of flash floods, but as it turned out, they were not the problem. Returning one evening, we unwittingly disturbed a moose, that in taking flight, uprooted some small trees and gathered up one of our smaller tents with sleeping bag and cloths inside. Following the trail of destruction, we eventually recovered a tattered bag and some other items; the tent disappeared. Unlike the incident with the wolf, there was little time to stand and admire this creature and its massive rack.

Assistant Phil developed an almost psychotic relationship with the insects that, admittedly, were diabolical. In camp he would devise all manner of tortures for the large deer flies, but his coup de grace was a cigarette lighter with which he attempted to ignite the creatures whilst in flight. He could claim some success at this, but his efforts also resulted in a largish hole in one wall of the main tent – fortunately it was treated cotton fabric rather than nylon or polyester, otherwise the entire tent would have gone up in flames. We were able to do a temporary fix on the hole. The cigarette lighter was banned.

Most of my field projects were in remote corners. I wrote screeds to my girlfriend, including one letter on Birch bark, and another on a small, Beaver-chewed, pointy-end stick. We still have these missives.

I can say I have been to Alaska. Admittedly it was a bit of a cheat. We were working on a ridge that, according to the topography map, continued across the border. No fences, or walls. A casual stroll across ridge lines, rocks, and a glorious array of alpine flowers and wild cranberries (a favourite of bears). We did not see a single bear, which perhaps was just as well; third time might not have been so lucky.