Final exams over, a moment of tomfoolery, and I found myself disconsolate in a hospital bed, recovering from an operation on a dislocated knee (no such thing as key-hole surgery back then). I had completed my BSc (November,1972) and was contemplating doing a Masters on something sedimentological. A visit from one of my professors, a period of impatient recovery, then loaded the aging Morris Minor and headed north almost as far as it is possible to drive in New Zealand. This was to be my first bona fide field project.

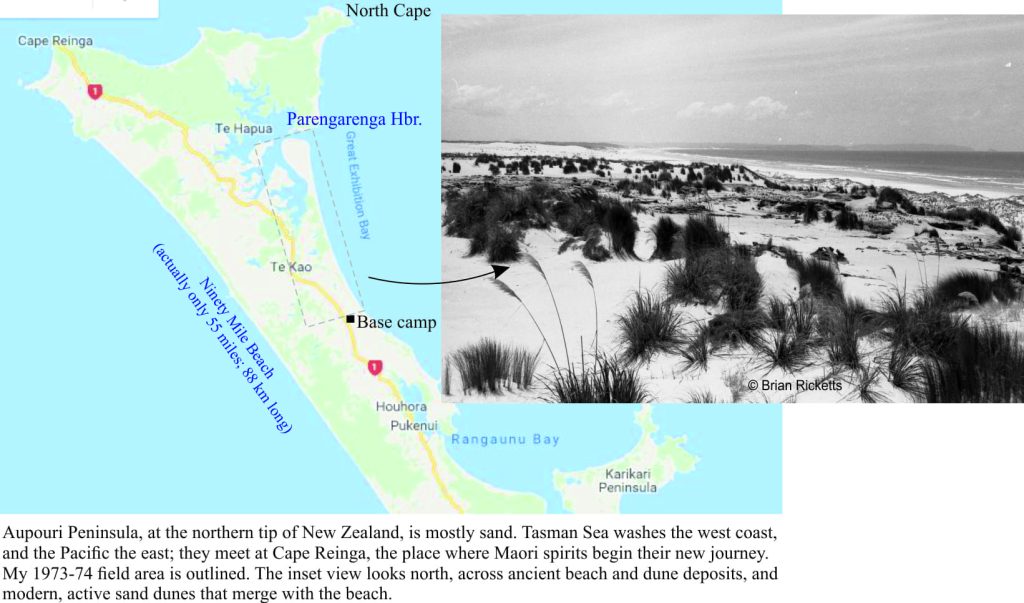

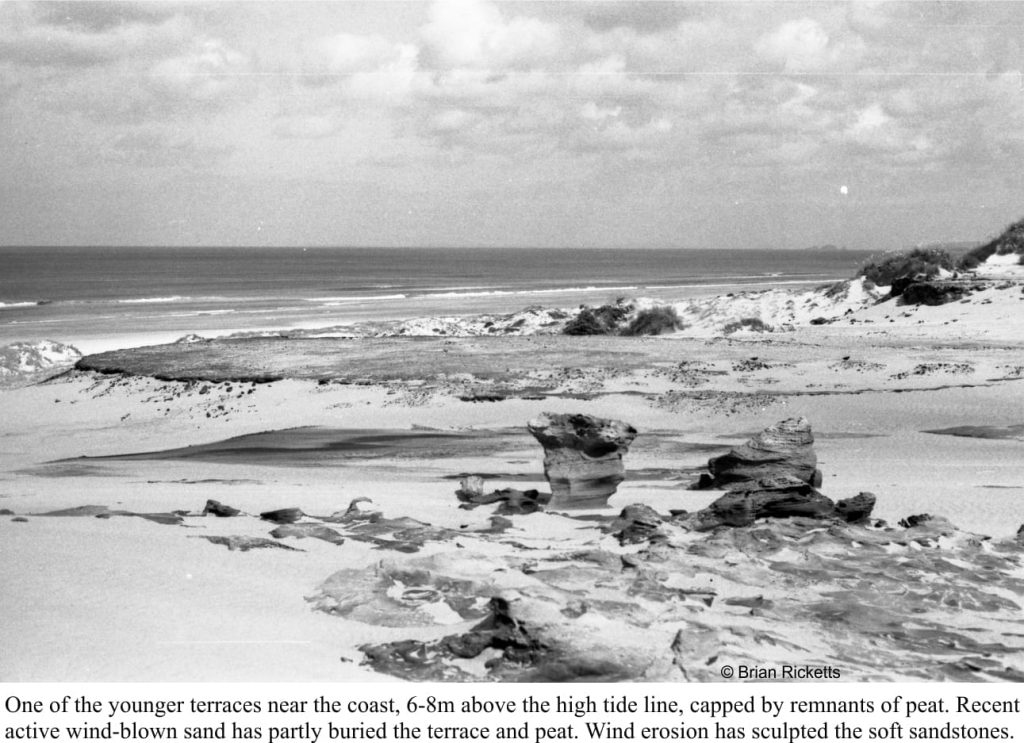

My field area incorporated a 22km stretch of glorious coastline that, at its northern extent, culminated in a sandspit (Kokota Spit) and Parengarenga Harbour. The task was to decipher the sand deposits, from the very recent to maybe a million or so years old. This narrow strip of land is part of the much larger Aupouri Peninsula, founded on sandy bars and spits that connect small islands and headlands of harder, older igneous and sedimentary rock. Tasman Sea washes the west flank of Aupouri, and the Pacific the east; the two seas meet at Cape Reinga, the place where Maori spirits begin their new journey.

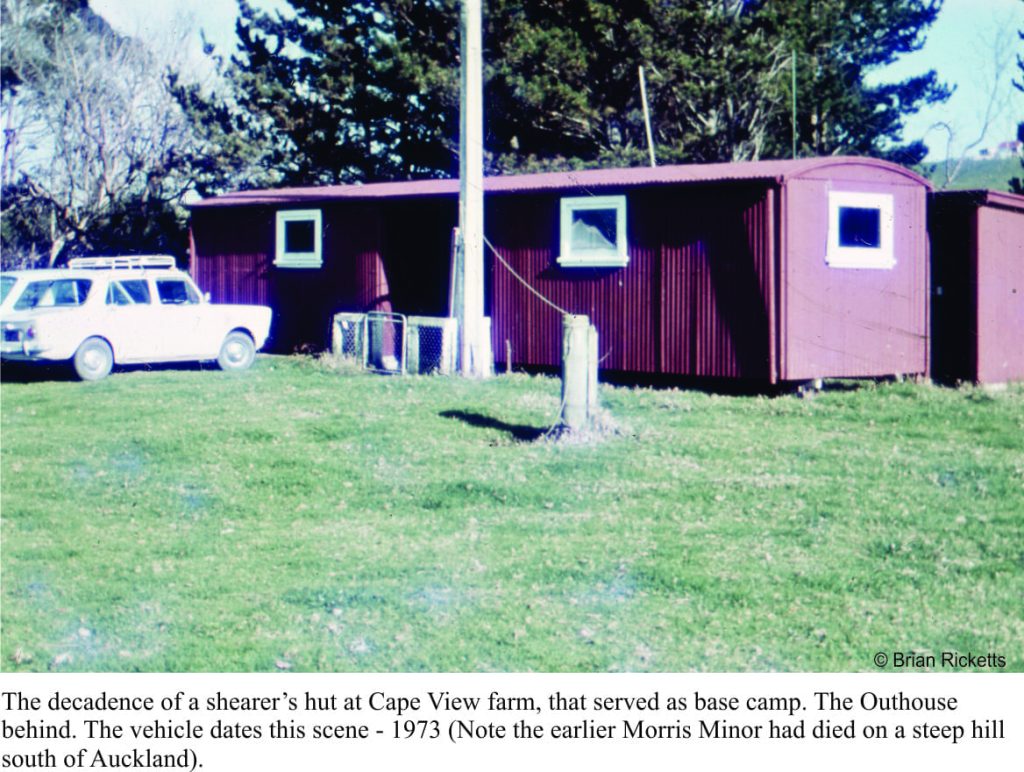

This part of New Zealand is stunning, and perhaps still understated. In the early 70s, it was sparsely populated. What roads existed then were gravelly. Except for cattle and a few farming folk, I had the entire coast, and most of the inland section to myself (plus the friends that inevitably turned up). My digs for the 1973 field season were a dilapidated shearer’s hut (nothing that a bit of flea powder couldn’t fix), close to the main road and about 2km from the beach. The hut belonged to a farming block called ‘Cape View’, administered by the central Government’s Lands and Surveys Department. There were several farm blocks in the area that, since the mid-50s, had been developed for sheep and beef farming. Cape View is now leased to the Maori-owned Parengarenga Incorporation (the road is also sealed). The hut was ideal – there was no charge for the 10 plus weeks I spent there, and the farm manager would occasionally deliver fresh milk or cuts of lamb (at times, the liver was still warm).

This part of New Zealand is stunning, and perhaps still understated. In the early 70s, it was sparsely populated. What roads existed then were gravelly. Except for cattle and a few farming folk, I had the entire coast, and most of the inland section to myself (plus the friends that inevitably turned up). My digs for the 1973 field season were a dilapidated shearer’s hut (nothing that a bit of flea powder couldn’t fix), close to the main road and about 2km from the beach. The hut belonged to a farming block called ‘Cape View’, administered by the central Government’s Lands and Surveys Department. There were several farm blocks in the area that, since the mid-50s, had been developed for sheep and beef farming. Cape View is now leased to the Maori-owned Parengarenga Incorporation (the road is also sealed). The hut was ideal – there was no charge for the 10 plus weeks I spent there, and the farm manager would occasionally deliver fresh milk or cuts of lamb (at times, the liver was still warm).

I had decided to try using a push bike for access – easy enough on the gentle farm tracks and I hoped, the beach. I had earlier driven the beach during a scouting trip, so I was able to calculate the wheel pressure of the vehicle on the sand, and compare it to that of the bike with me on it. Theoretically they exerted similar pressures. The happy coincidence of empirical tests and theory, meant that for the most part, my excursions along the beach were relatively easy and quick. Only occasionally was I brought to an abrupt halt by a patch of soft sand.

An added advantage with this mode of transport was the ability to carry flotsam and jetsam that was constantly strewn along the beach – subtropical molluscs, glass fishing floats, and bits of driftwood for the small fire I would light to cook shellfish for lunch (mostly Tuatua). I could also carry my Kontiki – an inflatable inner-tube with a small sail attached, that, whenever there was an offshore breeze, would carry a long line of baited fish hooks about 200m from shore. I mostly retrieved fish heads; the sharks and barracuda got the rest.

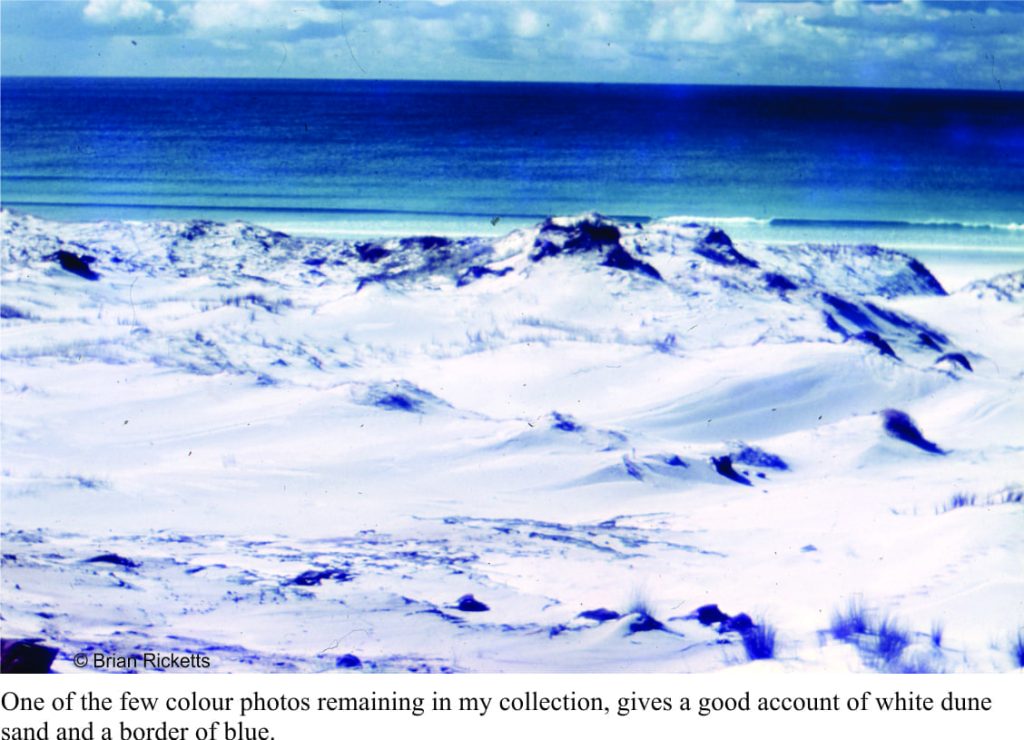

The sands along this stretch of beach are almost pure white; more than 95% of the sand grains are composed of quartz. Even in the heat of the day, the sand would stay cool, but the reflection meant sunburn under my nose, chin and even armpits. It was a fabulous place to work; sun, warmth, clear water, modern and ancient geological and geomorphic processes, and the promise of locally-derived snacks.

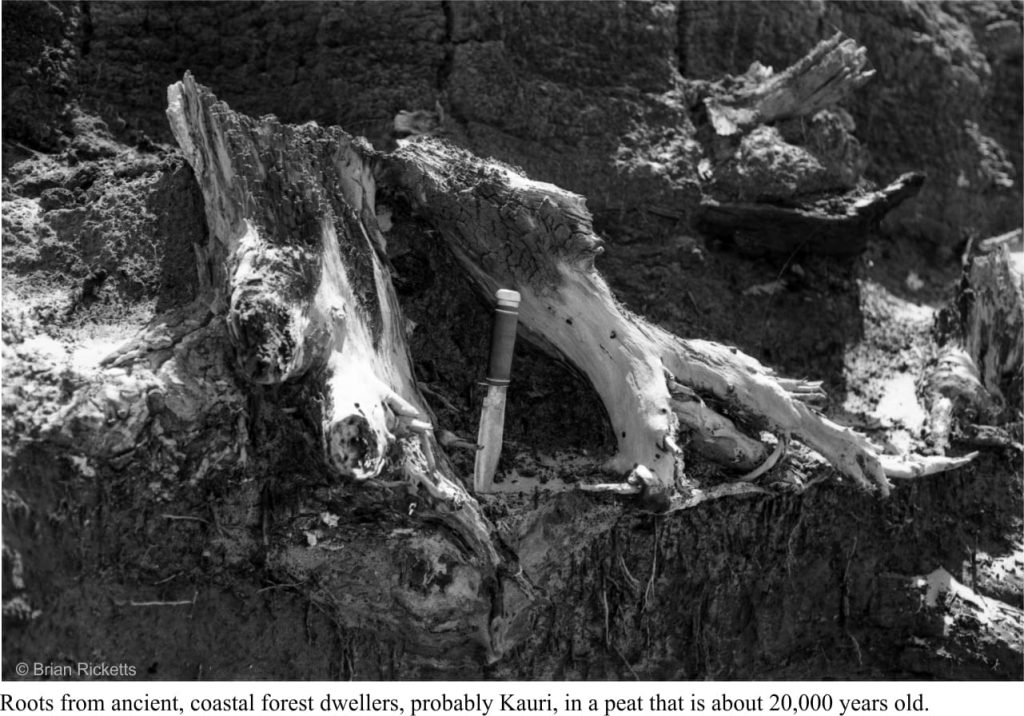

Some of the land surfaces were capped by old peats containing abundant Kauri roots, cones and leaves (Kauri is the Maori name for the endemic conifer Agathus australis). Over the millennia, coastal forests in this region had waxed and waned with rising and falling sea levels, the movement of sand, and changing climates. Most of these forests have gone now, burned and stripped by all and sundry over the past couple of centuries. In the 19th century, the peats were also plundered for prized Kauri tree amber (gum-digging). But the ancient peats, now exposed along sections of the coast, do provide a glimpse of what must have been a glorious coastal woodland; and birds galore. From time to time the sands give up some of their hidden treasures – bones that hint of a former morning chorus: North Island Kiwi, von Haast’s extinct Eagle (with a reputed 3m wing span), extinct endemic quail (not the Californian kind), Petrels, Prions, Gulls, Blue Penguins, and extinct Moas.

Along the main road (there was only one road) and a few kilometres south of the Cape View shearer’s hut, is the village of Houhora that, in 1973 and to this day, boasts New Zealand’s northernmost pub. Back then, being so far from any substantial population had its advantages, particularly regarding the ‘Last Call’. It was a pub with character. A juke box that seemed to work when it felt like it, a pool table with a level that seemed to change when visitors took on the local talent, and a rough floor that was kept free of chips and crumbs by the Publican’s flock of chickens that roamed at will (and probably ended up in the deep fryer). One evening a couple of sheep wandered through. No one took much notice. Nothing better than a cool beer after a day’s cycling and sampling, and when I could afford it, local fish-n-chips.

I spent a total of 14 weeks ‘at the beach’. I have never been back (and yes, I do regret this). I wrote my thesis, developed the black-and-white photos in the department lab, hand-drew all the graphics, and had the text hand-typed (my mother was appalled at the amount of white-out used). Thesis submitted.

I spent a total of 14 weeks ‘at the beach’. I have never been back (and yes, I do regret this). I wrote my thesis, developed the black-and-white photos in the department lab, hand-drew all the graphics, and had the text hand-typed (my mother was appalled at the amount of white-out used). Thesis submitted.

After thought: During the application to have my MSc conferred, the (Auckland) University admin informed me that I did not have a BSc. In my rush to get into the field I had forgotten to have that degree conferred. So, my BSc was ushered through the post-graduate Council a few weeks before the MSc was conferred (1975). The coincidence of dates on my CV has elicited some interesting comments from prospective employers.