Sedimentary structures that indicate paleoflow. Measuring and plotting paleocurrent indicators are treated in a separate post.

This post is part of the How To… series

Sediment that is moved along a substrate (e.g. the sea floor, river bed, submarine channel, wind-blown surface) will commonly generate structures that record its passing. Sedimentary structures that preserve directionality (paleoflow) are indispensable for deciphering whence the sediment came and where it went; for interpreting sedimentary facies (local scale) and sedimentary basins (regional scale). Paleocurrents are a measure of these ancient flows.

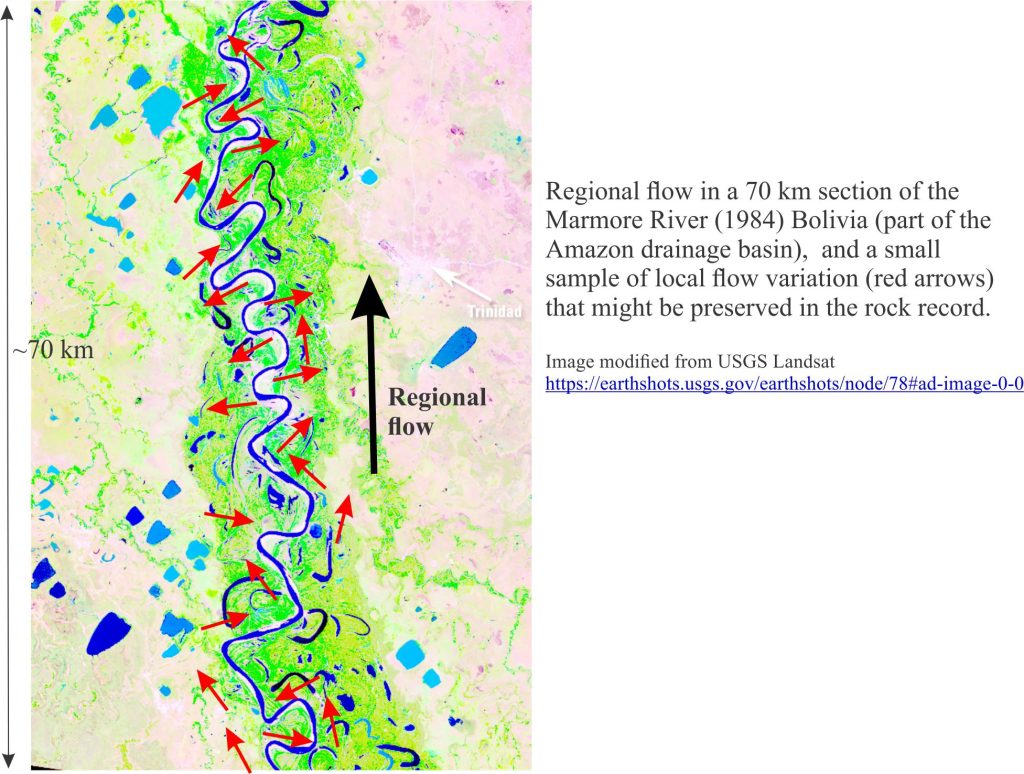

A single structure, such as a ripple will give a unique measure of paleoflow at a certain point in space and time. An important question for this single piece of data is – how relevant is it to the bigger picture of sediment dispersal? To get a sense of regional flow and sediment transport patterns, we need many measurements so that we can tease the overall pattern of flow from whatever local variations might exist.

We can illustrate this central problem by looking at flow in a fluvial meander belt with depositional settings like the main channel (arrows), point-bars and adjacent flood plain. This snapshot in time shows clearly the huge variation in local flow directions. We also need to account for other ‘snapshots’ in time, because even at a local scale (e.g. one meander bend and point-bar), the directions of flow and sediment transport will vary from flood to low water stage. We can try to circumvent this problem if we measure a large number of flow directions over an equally large area of the river and floodplain. In modern drainage basins this is straight forward but for the rock record, exposure is likely to be discontinuous and even structurally disjointed.

Structures indicating unique flow directions

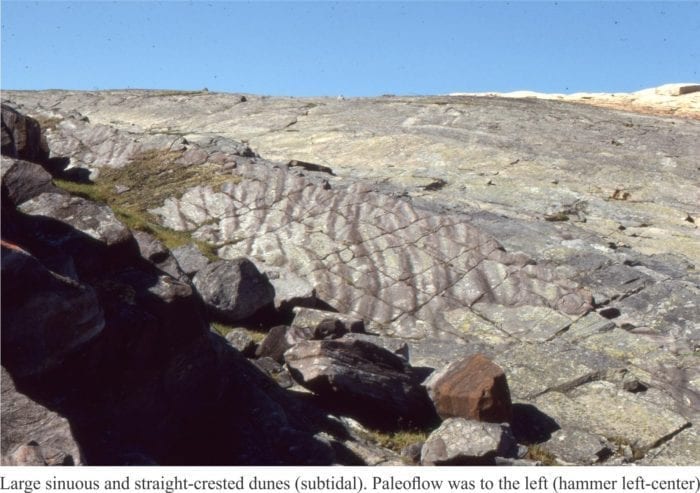

Subaqueous dunes and ripples: These bedforms are built by 2-dimensional (straight-crested) dunes and ripples. Hence, the boundaries between adjacent crossbed sets tend to be planar (cf. trough crossbeds). Flow direction is approximately at right angles to dune or ripple crests.

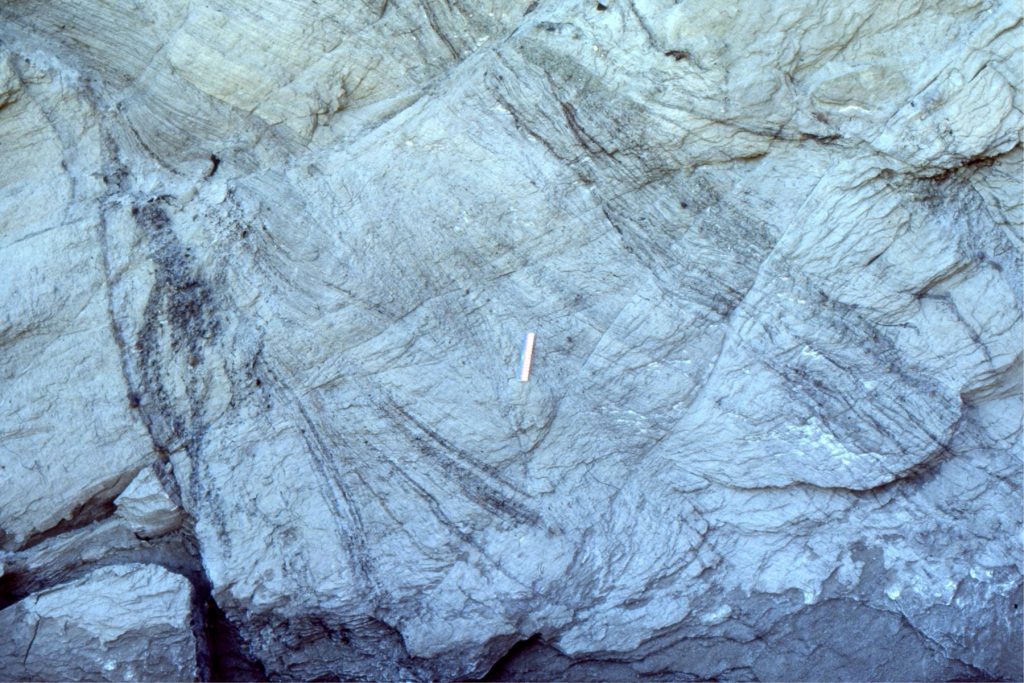

Trough crossbed, or 3D subaqueous dunes Spoon-shaped troughs filled by migrating, sinuous dunes produce trough crossbedding. This kind of crossbed is common in confined, channelized flow (e.g. fluvial and tidal channels). The mean flow direction is along the axis of the trough.

Left: Festooned trough crossbeds exposed approximately parallel to bedding. Paleoflow is the direction of the hammer handle Proterozoic Loaf Fm.). Right: Cross-section view of multiple trough crossbeds – only apparent flow directions can be surmised from outcrop (Eocene Buchanan Lake Fm.).

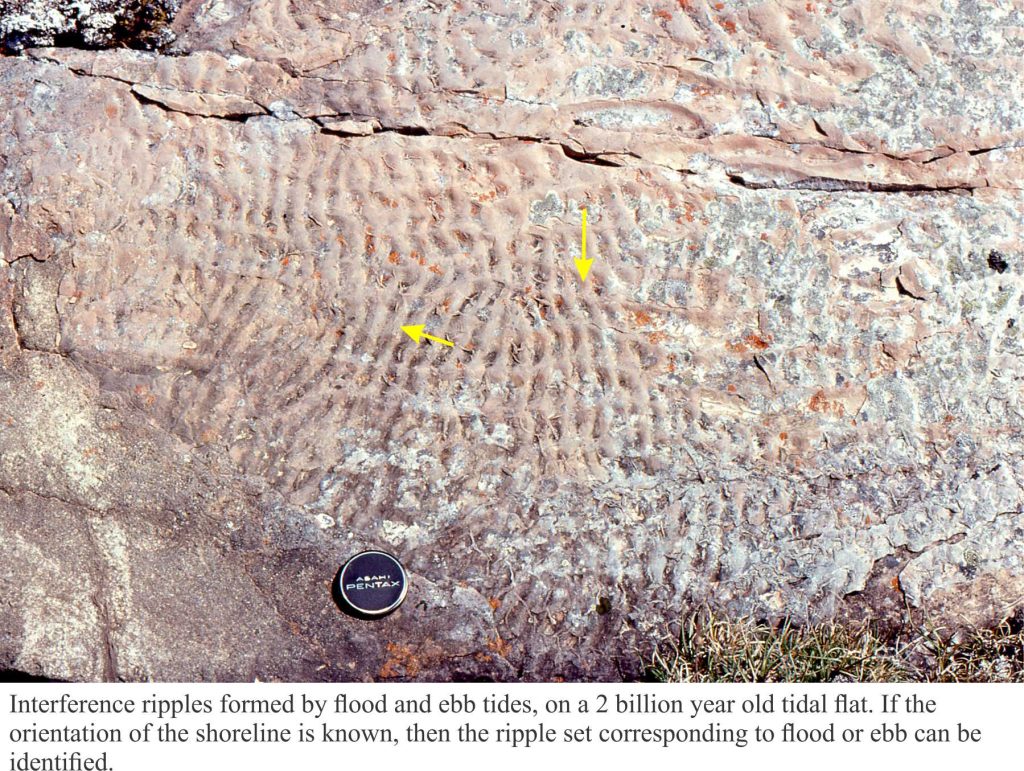

A caution about wave-formed ripples; This bedform does not arise from bedload transport in flowing currents, but from wave orbitals. Wave ripples are not paleocurrent indicators. However, wave ripple crests will be oriented approximately parallel to the strike of the ancient shoreline.

Imbrication Flat and platy clasts are commonly oriented by strong currents, such that the ‘plates’ dip upstream. These fabrics are common in gravelly fluvial deposits.

Imbricated platy cobbles and pebbles in a modern stream. Flow is to the right.

Imbricated platy cobbles and pebbles in a modern stream. Flow is to the right.

Flute casts Flutes originate from erosion of a soft, commonly muddy substrate and are filled with sand – they are part of the overlying bed and are usually seen as casts on the sole of the overlying bed. Flow direction is towards the open, shallow end of the flute.

Large flute casts on a turbidite bed sole (Omarolluk Fm, Belcher Islands). Flow was from top left to bottom right

Large flute casts on a turbidite bed sole (Omarolluk Fm, Belcher Islands). Flow was from top left to bottom right

Structures indicating ambiguous flow directions:

Groove casts Objects dragged across a soft substrate by strong currents (e.g. bottom currents, turbidity currents) will scour linear grooves that become filled by the overlying sedimentary layer. Like flutes, they are usually seen as casts on the soles of beds. In the absence of other indicators, the two possible paleoflow directions are 180o apart.

Groove casts on a bed sole, indicate flow in either direction. other criteria, like flute casts, are need to specify unambiguous flow directions.

Groove casts on a bed sole, indicate flow in either direction. other criteria, like flute casts, are need to specify unambiguous flow directions.

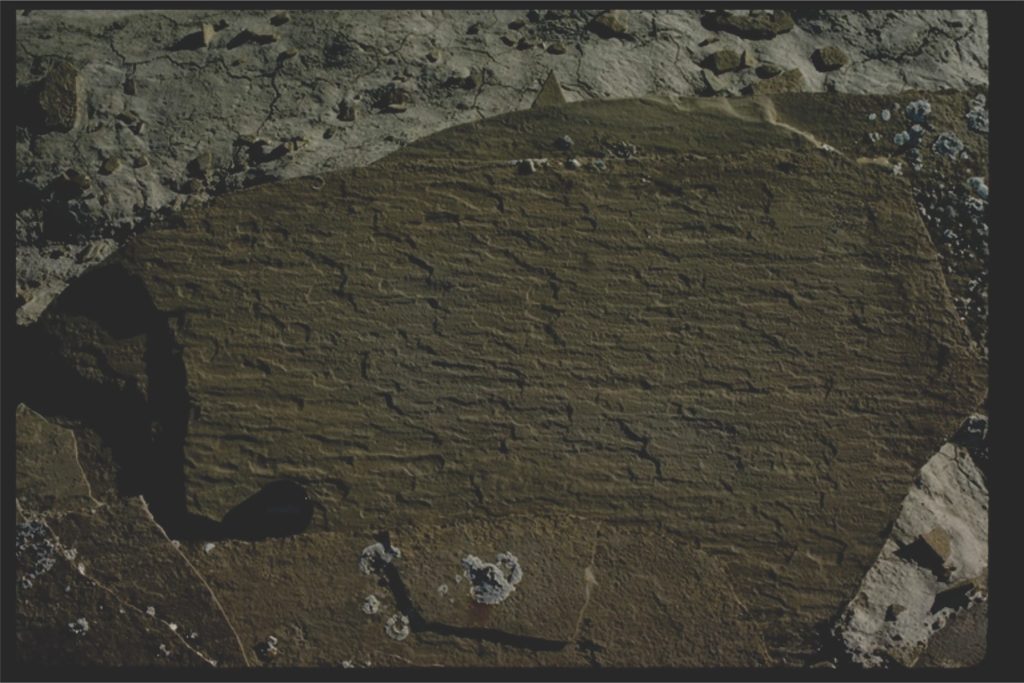

Parting lineation These are subtle structures 2 or 3 grains thick, that are visible only on exposed laminated bedding. The word ‘Parting’ refers to rock breakage along planar laminations. Parting lineation is attributed to high flow velocities where the long axes of sand grains become aligned (in Flow Regime terminology this corresponds to Upper Plane Bed conditions). Paleocurrents are measured parallel to the long direction of parting, but like groove casts, are ambiguous.

Paleoflow indicated in this parting lineation was either to the left or right.

Paleoflow indicated in this parting lineation was either to the left or right.

Current alignment of elongate fossils, rod-shaped clasts, or bits of wood can generally be treated like groove casts in terms of their paleocurrent value. There are exceptions; for example turreted gastropods may be aligned with their apices pointing downstream. The example shown here shows fairly consistent alignment of Permian Fusulinid foraminifera parallel to the prevailing flow (but the actual flow direction is ambiguous).

The classic text that deals with paleocurrent analysis is – Potter, P.E. and Pettijohn, F.J. (1977) Paleocurrents and Basin Analysis. 2nd Edition, Springer-Verlag, New York, 425 p.

Some more useful posts in this series:

Measuring a stratigraphic section

Measuring and representing paleocurrents