“Women Scientists Were Written Out of History” is an appropriate statement of introduction to this series on women geoscientists (quote from Susan Dominus, cited below). Evaluating the historical role that women played in emerging sciences is frequently plagued by a lack of written testimony, a problem that persisted well into the 20th century. Women might discover the first ichthyosaur (Mary Anning,1823-24), the molecular structure of DNA (Rosalind Franklin, 1953), or the Mid-Atlantic rift system (Marie Tharpe, 1953), but recognition was commonly ignored or relegated to footnotes or condescending remarks about their cleverness. One of the more telling anecdotes that epitomizes the social expectations of those times is the award of a Doctorate of Civil Law from the University of St. Petersberg to Etheldred Benett, promoted by Tsar Nicholas I of Russia and based on the quintessentially awkward assumption that Etheldred was a man.

Women were not permitted to publish scientific contributions (unless they were wealthy enough to self-publish), join scientific societies, or attend degree-granting colleges and universities until the late 19th to early 20th centuries. There were a few exceptions, such as Elizabeth Carne who published in the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall Transactions (1860-1875), and who also published in the London Quarterly Review under a male pseudonym. Elizabeth Agassiz also published jointly with her husband and later her son.. Frequently cited reasons for these strictures were fears of diluting the seriousness of scientific discourse, distracting the men from their learning, or the belief that women simply did not have the stamina for the rough and tumble of scientific debate. Unless diaries or correspondence were kept either by the women themselves or folk close to them, then historians are left guessing – were these pioneering women responsible for the ideas or interpretations, the collection, recording and analysis of data, the creative impulses that led to discovery, or were they just useful backdrops to a world dominated by the other 50%?

The last two to three decades have witnessed a surge in interest, and perhaps even a change in attitude towards the historical role that women played in emerging sciences. Mary Anning is feted in books and movies, and previously Hidden Figures have received recognition and accolades – often posthumously.

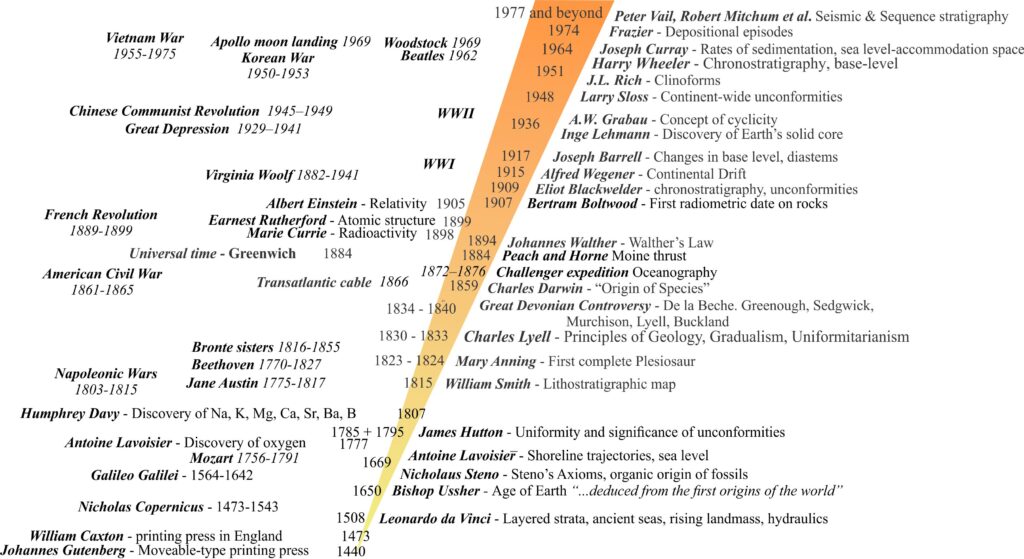

There are several ways to express the scientific, social, political, and religious contexts in which all these women lived and worked. The diagram below encapsulates a few of these events from the mid-15th to 20th centuries. To some extent the choice of items also expresses my own biases. The extent to which any of the women pioneers prior to the 20th C had access to knowledge of these events, particularly in the form of publications, is difficult to assess.

The biographies presented here are those relevant to the Earth sciences, primarily from the 17th to mid-20th centuries. They are brief, intended to introduce and direct readers to the more expansive and erudite accounts referenced.

[Initially, the list will be expanded alphabetically – I’ll eventually get to the W-X-Y-Zs. Other names and publication links will be added as they come to hand.]

Elizabeth Agassiz (1822-1907)

Annie Montague Alexander (1867-1950)

Mary Anning (1799-1847)

Florence Bascom (1862-1945)

Helen Belyea (1913-1986)

Etheldred Benett (1776–1845)

Martine Bertereau (1600 –1642)

Mary Buckland (1797-1857)

Elizabeth Carne (1817-1873)

Ingrid Christensen (1891- 1976)

Margaret Chorley Crosfield (1859-1952)

Gertrude Lilian Elles (1872-1960)

Regina Fleszarowa (1888-1969)

Eunice Foote (1819–1888)

Madeleine Fritz (1896 -1990)

Alice Wilson (1881-1964)

Maria Ogilvie Gordon (1864-1939)

Eliza Maria Gordon Cumming (1795-1842)

Mary Austin Holley (1784–1846)

Mary Emilie Holmes (1850-1906)

A few general references and websites, not in any particular order – (I will add more as they come to hand)

Marilyn Ogilvie, Joy Harvey (Ed.) 2000. The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: Pioneering lives from ancient times to the mid-20th century. Volume 1, A-K. Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-92038-4, pp. 485–486.

Susan Dominus 2019.Women Scientists Were Written Out of History. It’s Margaret Rossiter’s Lifelong Mission to Fix That. Women in Science, Smithsonian Magazine.

Association for Women in Science Celebrating Pioneering Women In Science.

Association for Women Geoscientists

Ferwen: Letters from Gondwana.

Max Plank Gesellschaft Women in science history.

Museum of Natural History, University of Oxford. Shout Out for Women in Science.

The Royal Society Pioneering Women.

U.S. National Science Foundation. Pioneering women in STEM.

Wikipedia. Timeline of women in science.

Elizabeth Reed, 1972. American Women in Science Before the Civil War. University of Minnesota, 1992.

Susan Turner, Cynthia V. Burek, and Richard T. J. Moody, 2010. Forgotten women in an extinct saurian (man’s) world. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, Volume 343, Pages 111 – 153

C. V. Burek, 2018. Archibald Geikie: his influence on and support for the roles of female geologists. Geological Society Special Publication.

Cynthia V. Burek, 2018. Archibald Geikie: His influence on and support for the roles of female geologists. Geological Society Special Publication 480, Chapter 4.

Panciroli E, Jackson PNW, Crowther PR, 2020. Scientists, collectors and illustrators: the roles of women in the Palaeontographical Society. Geological Society Special Publications Volume 506, p. 97 – 116.

Aude Vincent, 2020. Reclaiming the memory of pioneer female geologists 1800–1929. Advances in Geoscience, v. 53, p. 129-154. PDF available

C. V. Burek and B. M. Higgs, 2021. Celebrating 100 Years of Female Fellowship of the Geological Society: Discovering Forgotten Histories. Geological Society Special Publications, v. 506. Except for the Introduction, papers are paywalled.

E. Ellen Driggers, 2024. Glamour and Geology: Women in Petroleum Geology and Popular Culture. Springer Nature, 267 p.

Mariam K. Chamberlain (Editor): 1988. Women in Academe: Progress and Prospects. Russell Sage Foundation, 448 pages.