Glauconite – an important stratigraphic and paleoenvironmental indicator

Glauconite is one of the most recognizable minerals in the entire sediment suite, primarily because of its green hues, its common peloidal grain morphology, and microcrystalline structure. Green-ness does apply to a few detrital minerals like amphiboles, pyroxenes and chlorite, but they can be distinguished by their crystal habit and prominent cleavage; sedimentary glauconite is always microcrystalline.

Glauconite is a sheet silicate, distinctive in its high concentrations of Fe2+, Fe3+, and K. It occurs as different types depending on the relative proportions of Fe and K. Well-ordered (mature) glauconite is high in K (8% to 9%, derived from sea water) and its crystal structure is closest to that of micas. Precipitates with lower K contents tend to have more clay-like structure, particularly smectite (a mixed crystallographic bag of expandable clays). Total Fe is commonly >15%, and the amount of Fe3+ is usually > Fe2+ (B. Velde, 2014). Glauconites with low K and high Fe tend to have brown-yellow hues. Most glauconites begin precipitation as K-poor smectites that, over about 105 to 106 years, become increasingly K-rich and crystallographically ordered, or mica-like (Odin and Matter, 1981). The increase in crystallographic ordering can be measured using X-ray diffraction.

Glauconite is a marine, authigenic mineral that precipitates at very shallow depths beneath the sediment-water interface. This requires very low sedimentation rates, normal salinity and pH of the ambient seawater, and suboxic conditions where both Fe3+ and Fe2+ are thermodynamically stable. The oxidation of organic matter in peloids (particularly fecal pellets) and invertebrates may help push the oxidation state of Fe towards the 2+ state. Note that soluble Fe2+ will oxidize rapidly to relatively insoluble Fe3+ if exposed to normal, oxygenated, shelf sea water, forming compounds like limonite and goethite. Modern glauconite commonly accumulates at depths <300-500m on siliciclastic and carbonate platforms, shelves, and continental slopes. Ancient accumulations are frequently encountered as greensands.

The most common granular form of glauconite is sand- and silt-sized peloids. Other grain morphologies include vermiform (worm-like), tabular, mammillated, and composite types (e.g. Triplehorn, 1966). Glauconite can also replace or infill the chambers of bioclasts like gastropods, forams, bryozoa, corals, and the perforations in echinoid plates and spines. In hand specimen, they usually exhibit as dark green to black, sub-millimetre, ovoid pellets.

Accumulations of glauconite in the rock record are of great value because:

- They indicate a unique set of paleoenvironmental conditions.

- They are excellent indicators of stratigraphic condensation during transgression (look for a maximum flood surface at the top of the condensed section).

- They may coexist with phosphate nodules and phosphatized fossils (that also indicate condensed stratigraphy).

- Although they form authigenically, glauconite can be reworked locally. Glauconite can also be moved to deeper waters by sediment gravity flows. It is soft, friable, and has a hardness of 2 on the Moh scale, matching that of gypsum. Thus, it rarely survives beyond the first cycle of sedimentation.

Glauconite and glaucony

The name glaucony was introduced by Odin and Letolle (1980) for all forms of glauconite characterized by smectite clay crystal structure; the term glauconite was reserved for the mica-structured mineral end-member. However, the name ‘glauconite’ is firmly entrenched in decades of literature and for better or worse, I have continued with this literary laziness.

Glauconite (glaucony) in thin section

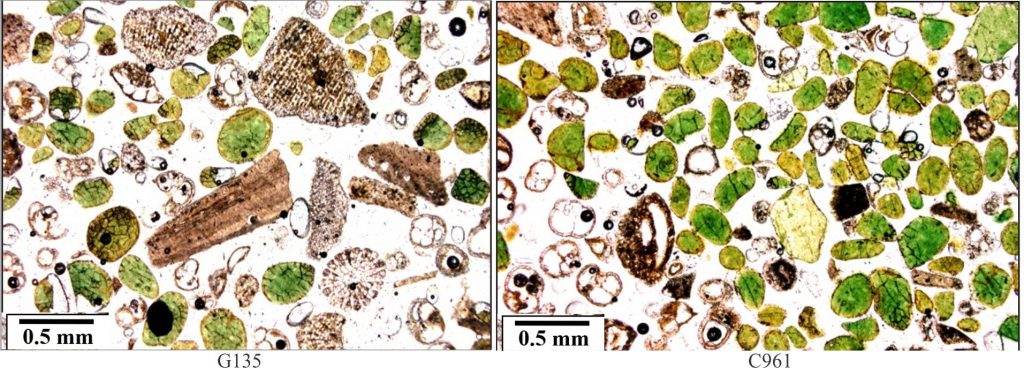

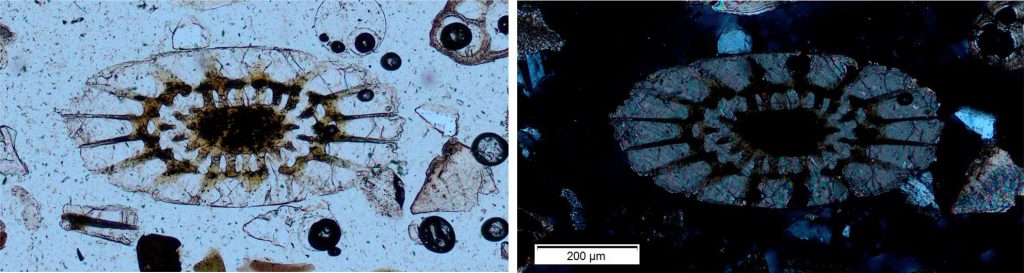

Chatham Rise

We begin with some glauconite-rich deposits from Chatham Rise, a ridge that is part of the submarine extension of Zelandia continent. The deposits form part of a highly condensed stratigraphic package dating back to the Oligocene and have been interpreted as palimpsest (relict) remnants of glacially lowered sea levels. Glauconite peloids that presently carpet the sea floor atop Chatham Rise have been K-Ar dated at 5-6 million years old (Nelson et al., 2021).

– Peloids are ovoid to tabular with smooth surfaces.

– Most peloids have quasi-radial or interconnected networks of cracks (dark brown – Fe oxide?). This is a common feature that mechanically weakens the grains such that they are unlikely to survive vigorous reworking or abrasion.

– Both examples contain planktic and benthic forams that show the beginnings of Fe-oxide-glauconite chamber linings.

– Image left contains fragmented echinoderm plates and spine cross-sections where perforations are partly filled with red-brown Fe oxide-glauconite.

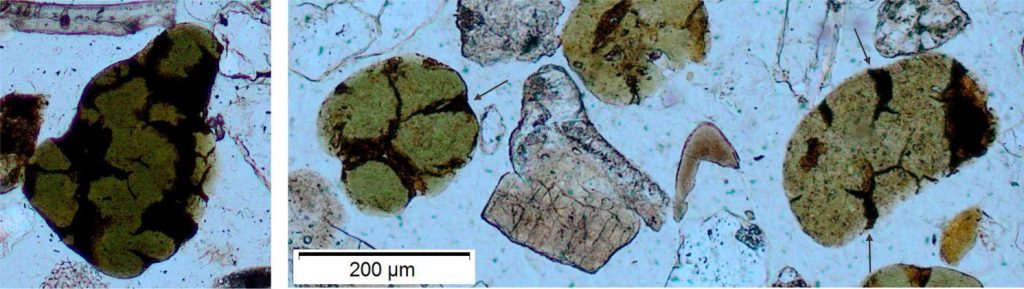

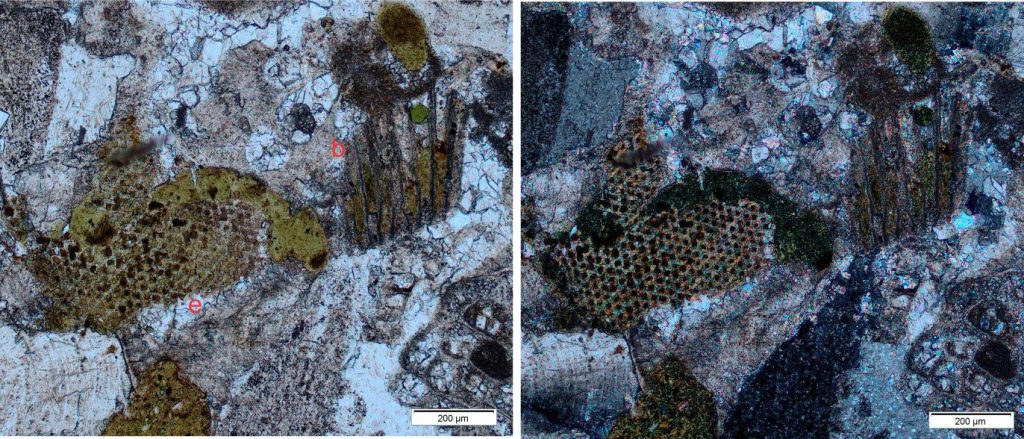

Modern sea floor, Three Kings Islands, northern New Zealand

The shallow, modern sea floor around Three Kings Islands is accumulating bioclastic sediment, dominated by bryozoa, forams, echinoids, barnacles, and molluscs. In this mix are glauconite pellets and glauconite infilled bioclasts.

Right: A rotaliid foram chamber (radial wall structure) partly filled by yellow-green glauconite and a few silt-sized fragments of quartz. The left side of the fill shows mammillated morphology. Plain polarized light.

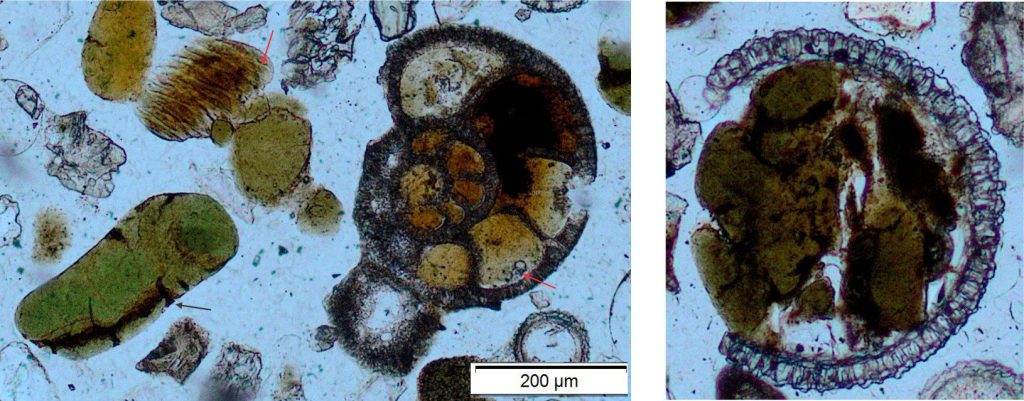

Glauconite infill of fossils

Examples from Oligocene bioclastic limestones, Te Kuiti Group, New Zealand

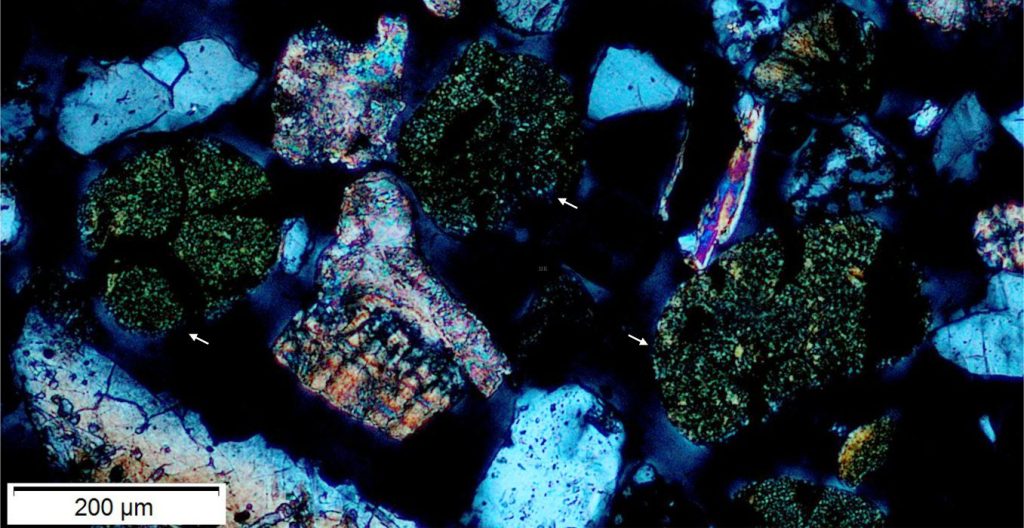

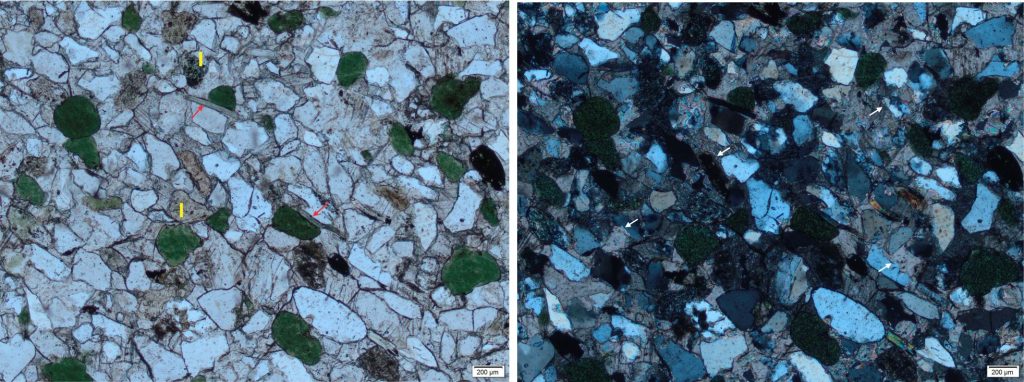

Glauconitic micaceous arenite

– Quartz grains (70-75%) are mostly monocrystalline (there are a few polycrystalline grains) and show a mix of unstrained and strained extinction. Grains are angular to well rounded, but some of the angularity is due to calcite replacement of quartz (some examples shown by white arrows).

– Untwinned K-feldspars (5-10%) show varying degrees of sericite alteration. Some appear superficially like lithic grains.

– Lithics (I) (~5-8%). Be careful to distinguish actual lithics from altered feldspar grains.

– White micas (1-2% – red arrows) show some alteration to chlorite (bluish interference colours).

– The framework clasts and micas have a crude alignment along the top left/bottom right diagonal.

– Cement is almost entirely coarse calcite. Contact between the calcite cement and framework grains is irregular, indicating silica replacement.

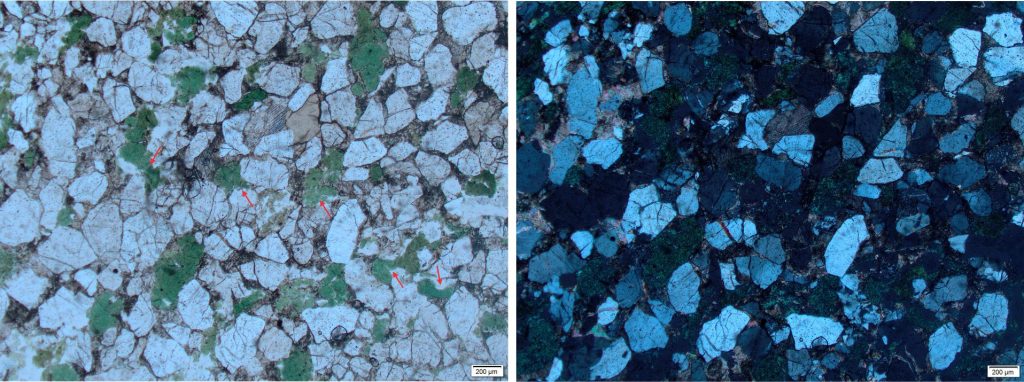

Glauconitic arenite

– The grains are more densely packed, with significantly less calcite cement and decreased calcite replacement of framework grains.

– The original peloidal shape of the glauconite grains has been distorted by compaction around stronger quartz-feldspar and squeezed between some grains (red arrows for some examples).

– Compaction has fractured some quartz grains – fractures are filled by calcite and possibly clays.

Other posts in this series

Brachiopod morphology for sedimentologists

Bivalve shell morphology for sedimentologists

Gastropod shell morphology for sedimentologists

Cephalopod morphology for sedimentologists

Optical mineralogy: Some terminology

Carbonates in thin section: Forams and Sponges

Carbonates in thin section: Bryozoans

Carbonates in thin section: Echinoderms and barnacles

Carbonates in thin section: Molluscan bioclasts

Neomorphic textures in thin section

Lithic grains in thin section – avoiding ambiguity

Mineralogy of carbonates; skeletal grains

Mineralogy of carbonates; non-skeletal grains

Mineralogy of carbonates; lime mud

Mineralogy of carbonates; classification

Mineralogy of carbonates; carbonate factories

Mineralogy of carbonates; basic geochemistry

Mineralogy of carbonates; cements

Mineralogy of carbonates; sea floor diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; Beachrock

Mineralogy of carbonates; deep sea diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; meteoric hydrogeology

Mineralogy of carbonates; Karst

Mineralogy of carbonates; Burial diagenesis

Mineralogy of carbonates; Neomorphism

2 thoughts on “Glauconite in thin section”

Can you please clarify whether glauconitic mica is identified by the same characteristics as glauconite exhibits under the petrographic microscope?

All the glauconite I’ve seen has been microcrystalline and so difficult, if not impossible to get any kind of interference figure, 2V etc. Larger crystals can occur; they are not common, but should be pleochroic in greens and yellows – if you do see larger crystals then cleavage and mottled appearance might be useful (like biotite, muscovite). But in seds as pellets or fills glauconite also can be mixed with clays (e.g., montmorillonite). X-ray diffraction would certainly help. Take care to distinguish it from other micas that have been altered to chlorite.

Hope this helps