Kawarau River – Rocks that have gone full circle

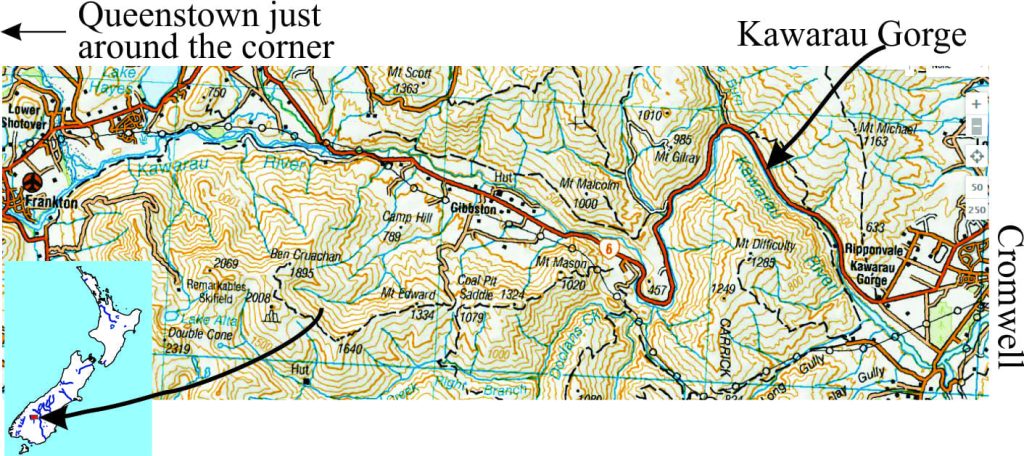

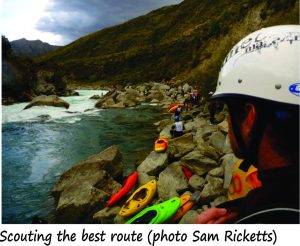

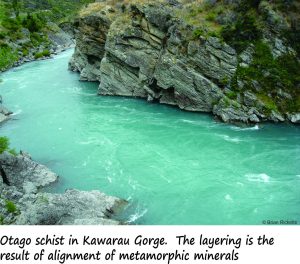

Kawarau River; kayaking and rafting mecca, water crystal-clear, torrents and gnarly rock faces. The river, incised into schist, Otago Schist, is a drawcard for whitewater junkies looking for challenging rapids (classes 2 to 5+). It has a bit of everything, apart from the whitewater – stunning, rugged hill country, easy access and proximity to Queenstown. Competitions, especially the Citroën attract local and international competitor. And for an added bonus, the region is also home to some of the world’s best Pinot Noir.

Kawarau River is sourced from Lake Wakatipu, one of the largest glacial lakes in New Zealand. After a 60km dash it drains into Lake Dunstan near Cromwell. Flows generally range from 100-400 cumecs.

The local geology is dominated by schist, a kind of metamorphic rock. Its formation may not have been as spectacular or violent as some of the volcanic events near Taupo and Rotorua, but it is just as fascinating; the end product, carved by Kawarau River, speaks for itself.

Like making a good wine, it takes time

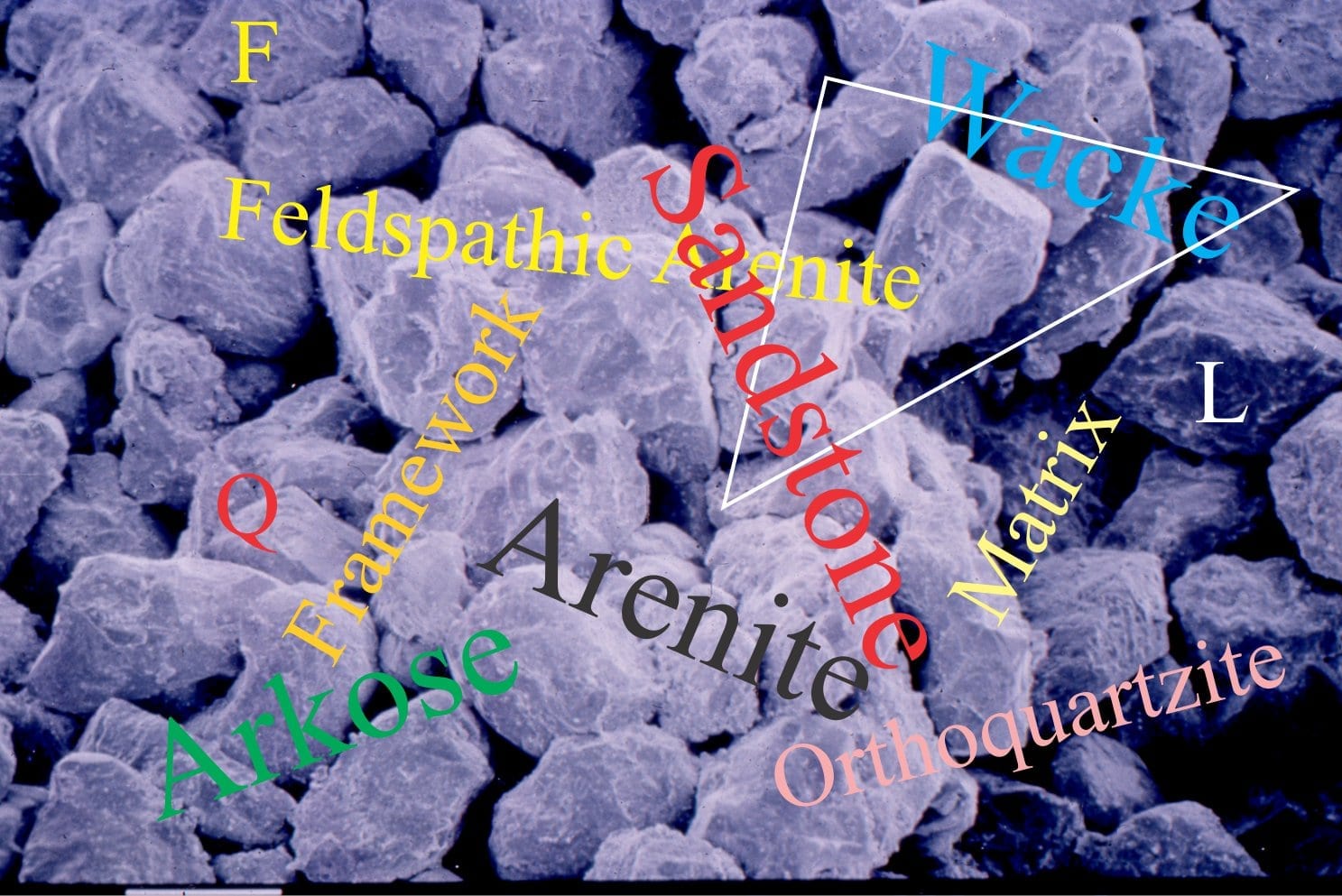

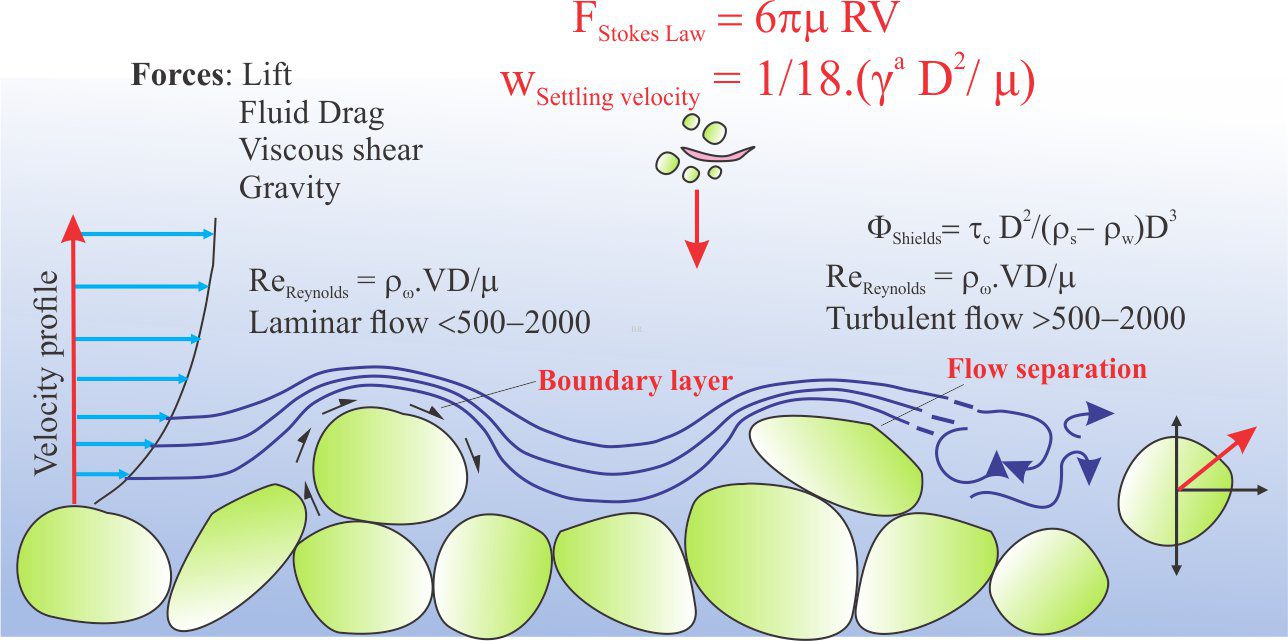

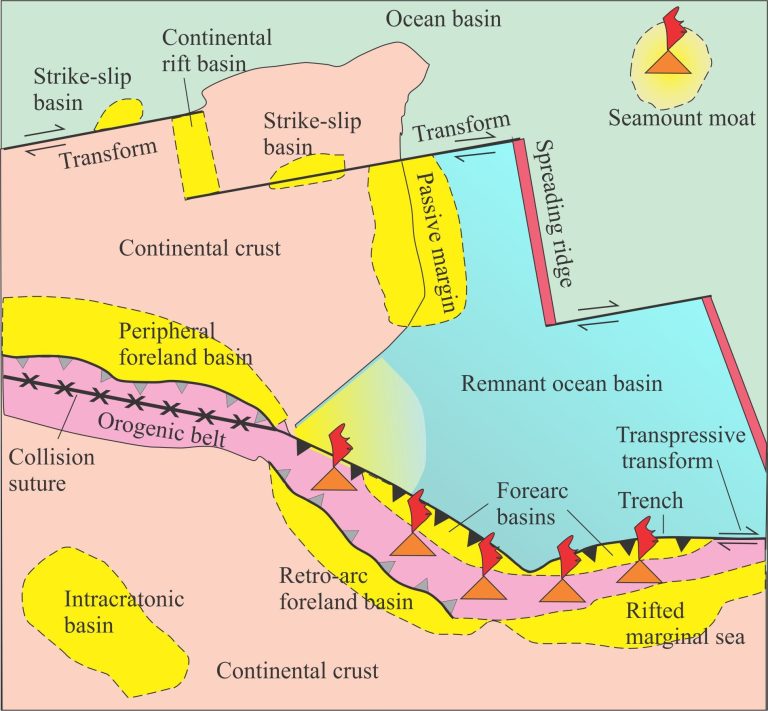

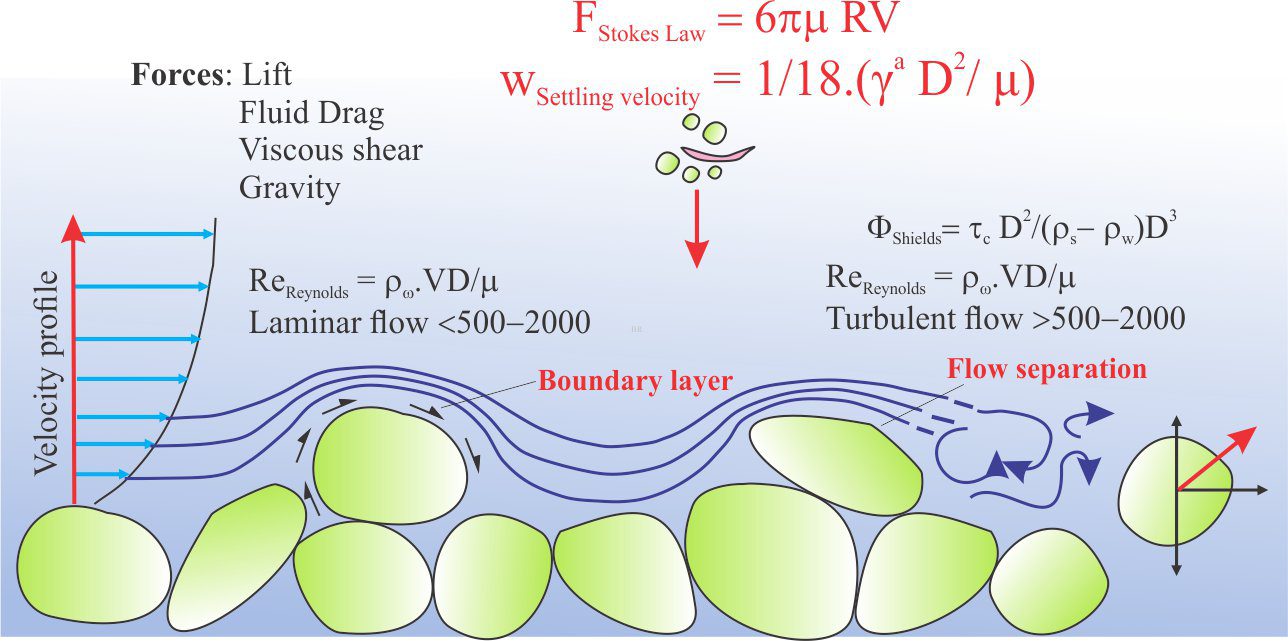

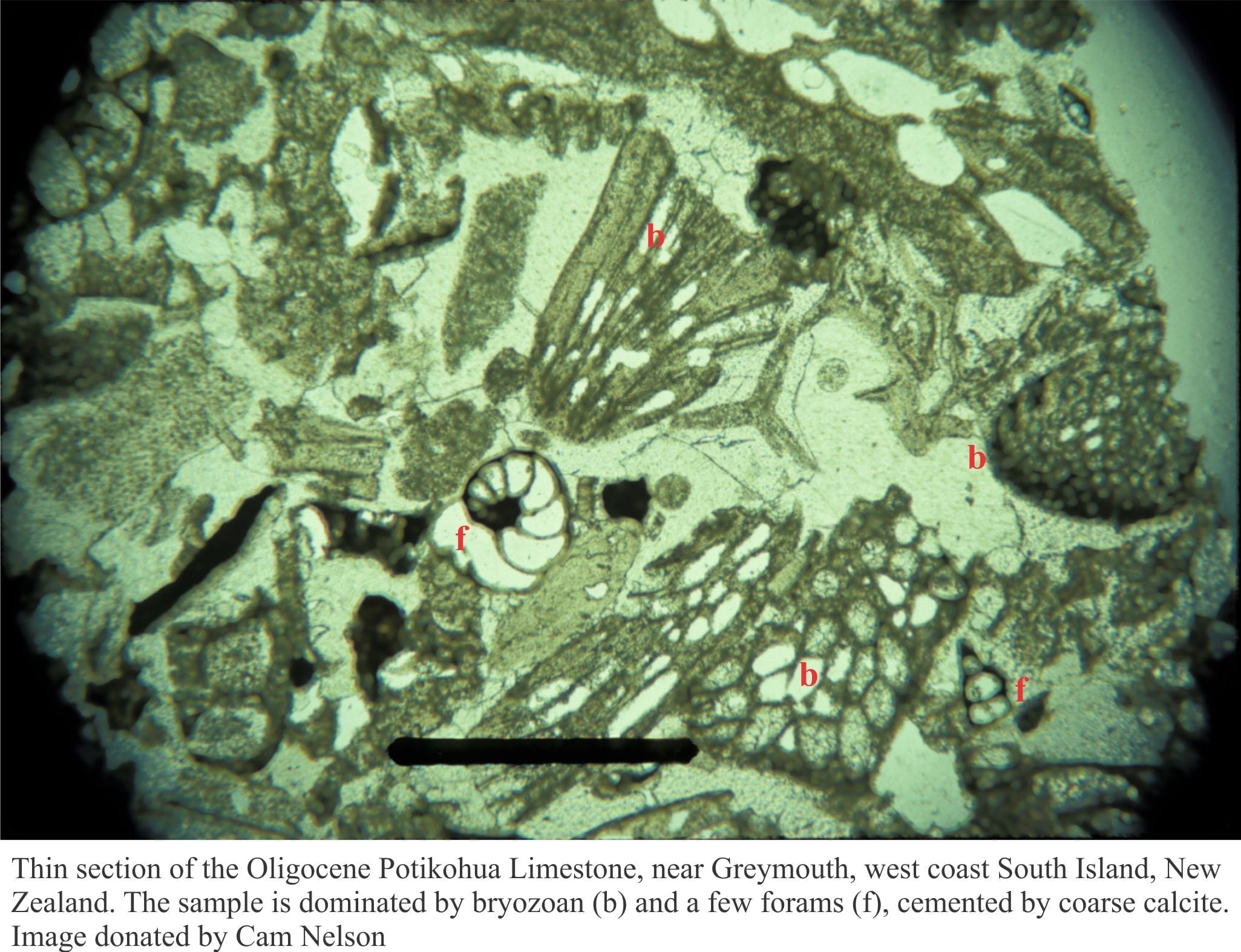

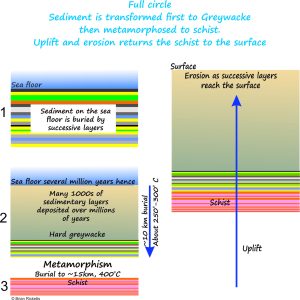

Metamorphism is part of a very grand system; it takes place in rocks that have been derived from other processes. In the case of the Otago Schists, the parent rock was greywacke (commonly used in construction and roads). Greywacke is a sedimentary rock that formed from the deposition of mud, silt and sand and gravel, including volcanic material, in large ocean basins. In New Zealand these rocks can be as old as 300 million years; they commonly form the backbone of mountain ranges in the North and South islands.

Sediment accumulation over millions of years resulted in a pile of strata more than 10 km thick. The sediment was compression and heated as it was buried deeper and deeper; at a depth of 10 km below the surface or sea floor, temperatures would have been about 250o-300oC. These conditions promoted chemical reactions that transformed the loose sediment into hard, hammer-ringing greywacke. For many New Zealand greywackes these rock-forming processes stopped at this point. However, Otago greywackes were buried still deeper, possibly 15km and more, with temperatures close to 400oC. And it was in this temperature and pressure environment that major changes to the rocks took place.

Sediment accumulation over millions of years resulted in a pile of strata more than 10 km thick. The sediment was compression and heated as it was buried deeper and deeper; at a depth of 10 km below the surface or sea floor, temperatures would have been about 250o-300oC. These conditions promoted chemical reactions that transformed the loose sediment into hard, hammer-ringing greywacke. For many New Zealand greywackes these rock-forming processes stopped at this point. However, Otago greywackes were buried still deeper, possibly 15km and more, with temperatures close to 400oC. And it was in this temperature and pressure environment that major changes to the rocks took place.

Metamorphism

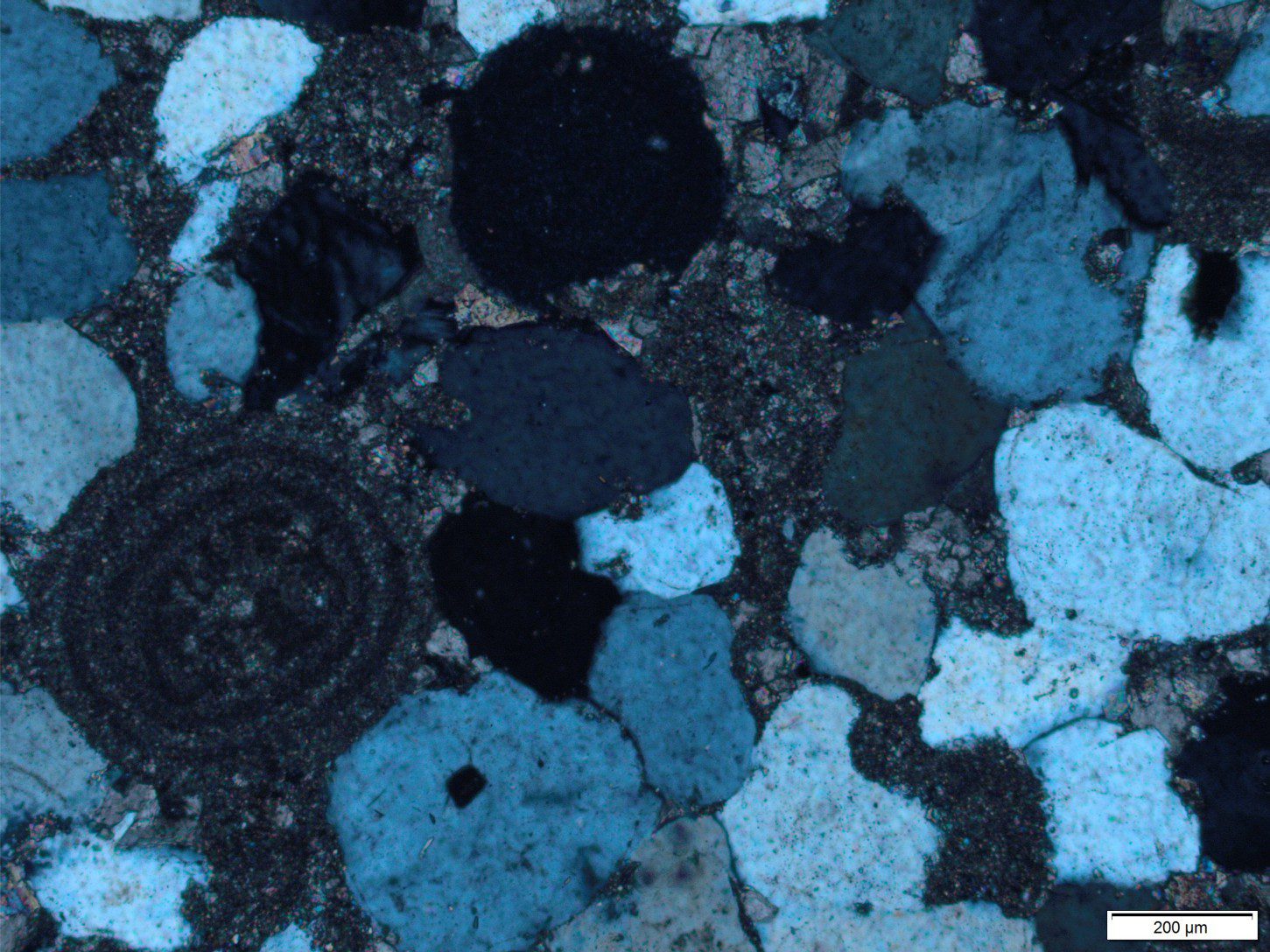

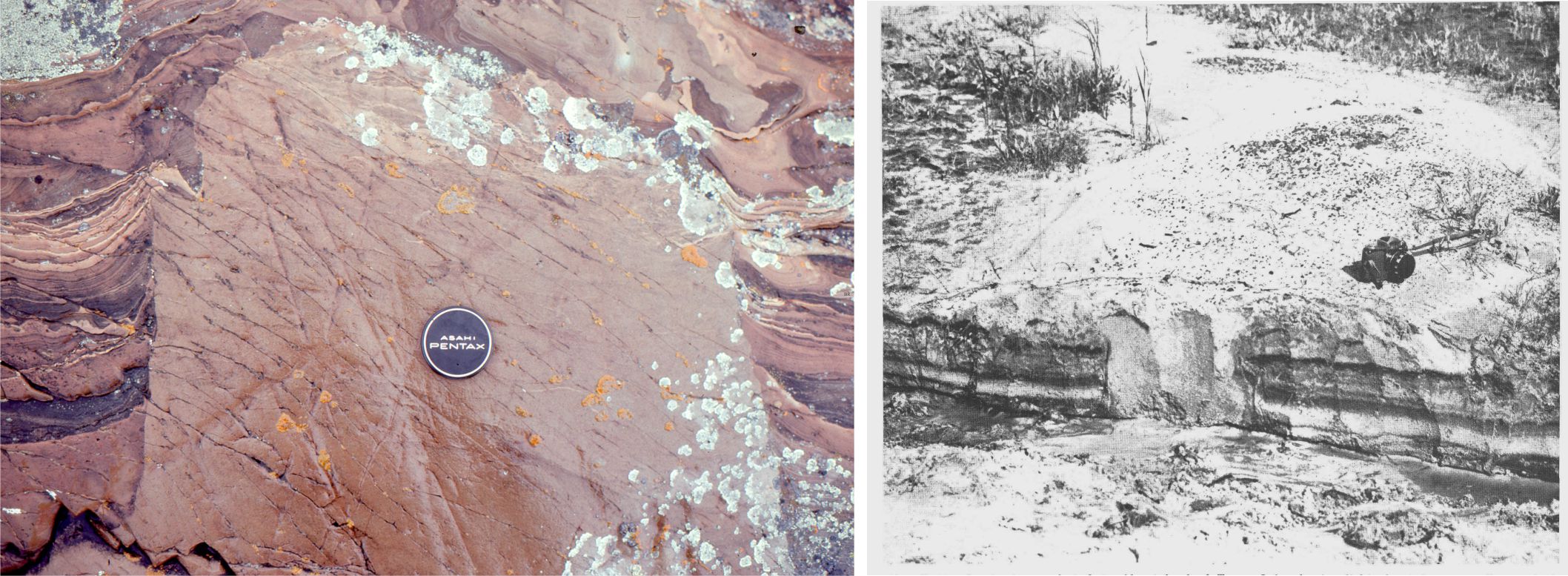

When sediment is deposited it contains grains of different mineral types; common minerals include quartz, various kinds of feldspar, clays (in the mud), and small chips of older rock. Metamorphism (which is a variation on the Greek word metamorphosis, meaning to change or transform) involves the transformation of the original mineral composition of the sedimentary rock into a new suite of minerals. Schists, like the Otago variety, have undergone an almost complete change;  the schists still contain quartz and feldspar but they are different crystals to the ones originally present. New minerals also formed, the most obvious being biotite, a mica that gives the schist a brilliant sheen. Mica crystals are very flat, almost paper-like in thickness. All the minerals form an interlocking mosaic. The abundant micas aligned with quartz and feldspar are also largely responsible for the platy, layered (foliated) character that is typical of schist.

the schists still contain quartz and feldspar but they are different crystals to the ones originally present. New minerals also formed, the most obvious being biotite, a mica that gives the schist a brilliant sheen. Mica crystals are very flat, almost paper-like in thickness. All the minerals form an interlocking mosaic. The abundant micas aligned with quartz and feldspar are also largely responsible for the platy, layered (foliated) character that is typical of schist.

Full circle

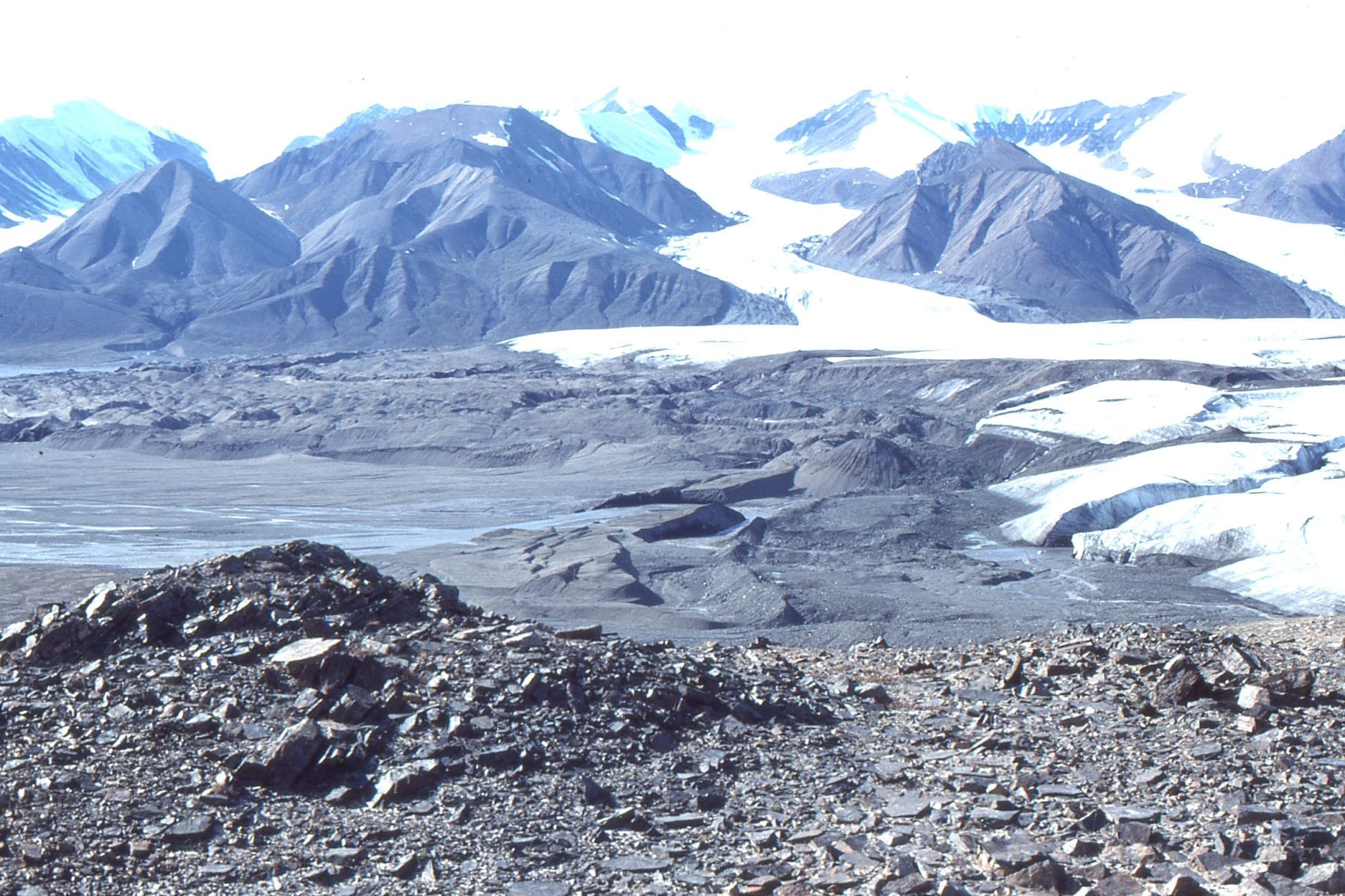

In Otago, the peak of metamorphism was about 170 million years ago (this means that the rocks were at their maximum depth of burial and maximum temperature). The fact that we can now see and kayak over these rocks means that they were pushed up about 15 km over the intervening 170 million years. But moving 15 km of rock is no mean feat; in other words, in order to see the schists, the 15 km of rock that lay on top of them must have been removed by eroding elements like wind, rain, glaciers, and rising and falling seas.

The schists through which Kawarau River rushes, have been on a really protracted journey; they were buried as sediment deep in the bowels of the earth, then pushed back to the surface again. And in the interim, they were metamorphosed, almost beyond recognition. The river itself has also played a part in molding the landscape. If you can, stop and think about the time and processes that have created this landscape; it’s quite humbling.

For more images check out Sea to Sky Whitewater