This biography is part of the series Pioneering women in Earth Sciences – the link will take you to the main page.

The accolade frequently appended to Elizabeth Gray’s name is that she was Scotland’s “foremost fossil collector”. The image this might conjure is of a Mary Anning-like figure, dust on her well-worn boots, wielding a hammer over rocky bluffs and rubble in search of Lower Paleozoic fossils. Probably not far from the truth given some of the field photographs that have survived.

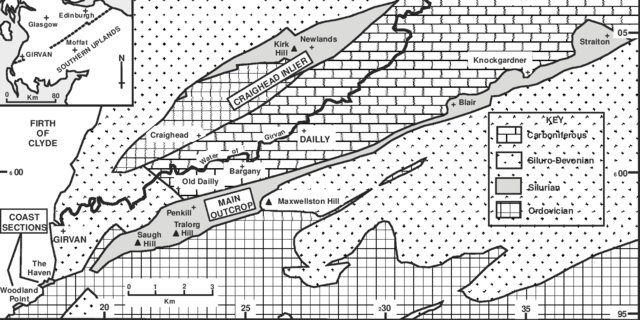

Gray’s passion for collecting was probably borne of a childhood spent on trips with her father, a keen amateur collector but not one acquainted with the Geological Society-like gentry. The family had moved to Girvan, a coastal town about 80 km south of Glasgow; most of her collecting for the next 80 odd years was from the Lower Paleozoic rocks in this area. Brief stints at a private school and a boarding school probably laid the foundations for her communication skills, but being female she would not have had access to the burgeoning Natural Sciences. Was she frustrated with this? After all, almost anyone who avidly collects fossils, or any natural history objects, usually wants to know more about them. Her only formal “geological” education wasn’t presented until she was 37 (1868), when she was invited by Professor John Young to attend a series of lectures at Glasgow University. At this time, she had already been married for 12 years (Cleevely, Tripp, & Howells, 1989).

Elizabeth (née Anderson) married Robert Gray in 1856, a banker by profession but an avid ornithologist. His own amateur interests in the natural sciences led him to co-found the Natural History Society of Glasgow in 1851. Notable scientists who at one time or another served as Society president included Sir William Thompson (Lord Kelvin), Archibald Geikie, Charles Lapworth, and Benjamin Peach (of Moine Thrust fame). The couple shared a passion for collecting and investigation and contributed papers to the Natural History Society, although Robert was always the lead author and presenter at Society meetings.

The NHSG did not explicitly exclude women members, but they certainly weren’t encouraged – at least until the first two women were added to the members list in 1886. The available Society history (e.g., Downie, 2001) makes little headway on why this situation existed, but the reasons for their exclusion were probably like those recorded in the proceedings of other science societies, like the Geological Society of London and the various Royal societies (the Royal Society of Edinburgh did not admit women until 1945): women were not suitably intelligent or capable of intellectual rough and tumble, were spoilers of male camaraderie and the powerful old boys’ network, or pure misogyny (read a brief note on these 19th C attitudes in the post on Margaret Crossfield).

The fossiliferous rocks Elizabeth Gray became engrossed with are Lower Paleozoic, now known to include Ordovician through Carboniferous strata around Girvan, and Ordovician to Silurian along the coastal exposures. In places there is an abundance of faunas including various molluscs, trilobites, brachiopods, corals, and graptolites. She became adept at recording the stratigraphic position of her specimens with notes and sketches – the rationale for detail was her wish that the collections would be used by “more learned” men of science “feeling that she could not hope to equal the authority of those who had devoted their lives to investigating particular branches of palaeontology. Instead, she preferred to devote her own energies to provide such specialists with ample material to complete their descriptions and interesting specimens upon which they could conduct their research, since her real enthusiasm lay in discovering and collecting fossils.” (quote from Cleevely et al., 1989, p. 173.

Indebtedness to Gray’s collections

Cleevely et al., 1989 describe the use of Elizabeth’s collections by several contemporary geologists (listed below). Collections were frequently sent to individuals with the proviso they be returned to her. One of the more important of these was Charles Lapworth, not only because of his forays into Cambrian-Ordovician-Silurian stratigraphy, but also his friendship with the Grays, initially through Robert – Lapworth made several mentions of specific fossils in Elizabeth’s collections at NHSG meetings (that Elizabeth could or did not attend – probably reported back to her by husband Robert). Lapworth also spent time in the field with her – many of the other recipients of her generosity did not.

The list of gentlemen and one lady geologist who benefited from her expertise is a good reflection of her collecting, specimen preparation, and recording abilities. Several species she collected became type specimens, some of which were named in her honour (e.g., Cyrtograpsus grayianus (a graptolite) Cothurnocystis elizae; an ancestral starfish). Individuals who used her collections focused on brachiopods, gastropods, trilobites, graptolites, corals, bryozoa, and asteroids (starfish):

Thomas Davidson (1817-1885) – in his monograph on the British Fossil Brachiopoda (1866-1871).

Charles Lapworth (1842-1920). Lapworth appears to have spent considerable time in the field with Elizabeth, and when he wasn’t present, he requested that she look for specific fauna, particularly graptolites, or the faunas from particular beds. Lapworth’s fame rests very much on his recognition and definition or the Ordovician Period (between the Cambrian and Silurian) for which graptolites were key to correlation of strata across England, Scotland, and Wales. Lapworth also worked with Gertrude Elles, Ethel Wood, and Margaret Crosfield, contemporaries of Gray although there is no indication they ever met.

H. A. Nicholson and R. Etheridge. Jnr. These gentlemen were responsible for the first monograph on Girvan fossils – much of the material supplied by Gray.

F. R. Cowper Reed (1869-1946). Dealt mainly with the trilobites and brachiopods of Girvan.

William Kingdon Spencer (1878-1955). Spencer dealt with Lower Paleozoic starfish, and was impressed with Gray’s collection, commenting that it was “…the best collection of Palaeozoic Asteroids in existence.” (in Cleevely et al, 1989, p. 188).

Mrs. J. Longstaff (nee Donald) (1855-1935). According to her friend and colleague Dr. Bather, “Jane Donald (w)as the only possible person in the country who could work on her large collection of Gastropoda.” (in Cleevely et al, 1989, p. 189).

Thomas Henry Withers (1883-1953). Withers became an expert on Paleozoic Cirripedes, particularly fossil barnacles describing some of the first to have been found in Gray’s collection.

Dispersal of the Gray collections

The earliest acquisition in 1866 by the Hunterian Museum (located at Glasgow University) was a general collection made by Elizabeth, her father, and husband Robert. It was sold for £35 (todays value would be about £4000). The Geological Survey purchased 1100 specimens for £50 in 1890 or thereabouts. Several smaller collections were also acquired by the Sedgwick Museum (Cambridge University) between 1907 and 1910.

Negotiations with the British Museum of Natural History (now the Natural History Museum, London) began in 1914 shortly before the beginning of World War I. Elizabeth’s contact there was Arthur Smith-Woodward, a prominent paleontologist who specialised in fossil fish. Discussions between Elizabeth and the BMNH began afresh at the cessation of the War and continued until 1920 – she was a tough negotiator on price and collection content. The museum at this point wanted to acquire the “entire collection” including type specimens of various species. After much haggling, the agreed price was £2250 that would be paid out over four years. The BMNH thus has the largest of the Gray collections (Cleevely et al., 1989).

Honours bestowed late in life

Elizabeth Gray’s public accolades came late in life, the first in 1900 – she was 69. The honours were primarily in recognition of her contributions to paleontological literature. This was a bit disingenuous because she had actually contributed in significant ways to many of these publications.

- Honorary Member of the Natural History Society of Glasgow (1900).

- The Murchison Fund in 1903 by the Geological Society of London. Society rules meant she could not accept this award in person, but Charles Lapworth was President at the time and did this on her behalf.

- Fellow of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh.

Elizabeth Gray remained an avid collector even at 92. She passed away on February 11, 1924, a few weeks shy of her 93rd birthday.

References and other publications

R.J. Cleevely, R.P. Tripp, & Y. Howells, 1989. Mrs Elizabeth Gray (1831-1924): A Passion for Fossils. Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History, Series 17, p. 167-258. Can also be accessed on the Biodiversity Heritage Library

J.R. Downie, 2001. 150 years of Glascow Natural History Society. Glasgow Naturalist, v.23 p. 57-61.

Elsa Panciroli, 2015. Elizabeth Anderson Gray. Trowelblazers.

Ferwen,2018. Forgotten women of Paleontology: Elizabeth Anderson Gray.

R. Weddle. Some significant women in the early years of The Natural History Society of Glasgow.