This biography is part of the series Pioneering women in Earth Sciences – the link will take you to the main page.

There is a palpable eagerness nowadays to recognize those women of the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries who themselves would have claimed a sense of professional pride in being naturalists, geologists, or paleontologists, but were excluded from most scientific societies and academic institutions because of their femaleness. Women were generally excluded as ‘real’ or professional scientists because of class, political structures, various laws, and the arcane rules of institutions that promoted the progress of science. But there were more disturbing reasons for exclusion where, either collectively or individually, men considered women to not be smart enough, to not have the temperament (except for tedious work), were not suited to the rough and tumble of vigorous debate, were “nasty forward minxes” (Adam Sedgwick – in J.W. Clark and T. McK. Hughes, 1890), a threat to their own elevation in the scientific community, or a threat to the coziness and camaraderie of their singularly male gatherings.

Eliza Gordon Cumming of Altyre became an expert collector of Devonian fossil fish, principally from the Old Red Sandstone. She prepared, identified, cataloged, and with her daughter Lady Anne Seymour illustrated a paleontological collection that attracted the attention of eminent scientists like Louis Agassiz, as well as indulgent aristocratic amateurs.

[The Altyre Estate near Moray Firth, Scotland, has been the family home of the Cumming Clan for more than 800 years]

Lady Gordon Cumming was also of the (Victorian) aristocracy and probably found it relatively easy to communicate with the leading geologists at that time – the likes of Agassiz, Buckland, Sedgwick, Murchison, Lyell. Her estate boasted a sandstone quarry from which many of the fossils were excavated. She was also very generous, gifting fossils and data (identifications, stratigraphy) to serious scientists and collectors. Agassiz in particular, an internationally acknowledged expert in fossil fish was the happy recipient of many specimens. So too was a well-known collector-amateur, The Earl of Enisskillen. It appears that he was only interested in amassing a collection of Devonian fish, and although he may have been able to recite genus and species, he wrote “next to nothing in geology” (Malcolmson, 1998 quoted in M. Orr, 2021).

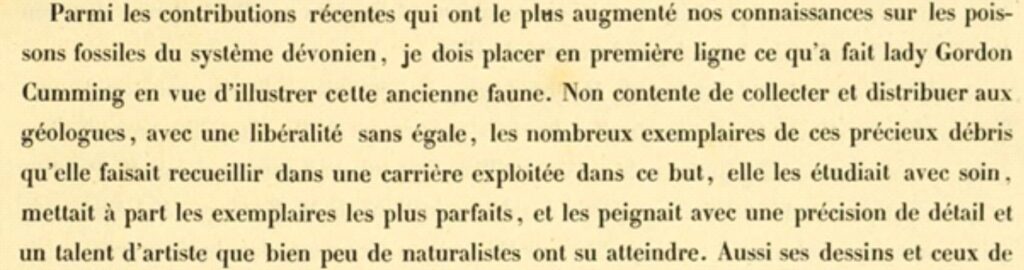

Right: A specimen of Cheirolepis cummingiae collected and illustrated by Eliza Gordon Cumming and described and named after her by Agassiz on p. 45 of the 1844 Monograph of fishes from the Old Red Sandstone. The title page is on the left.

Notwithstanding Gordon Cumming’s generosity, the recipients never incorporated her into their respective papers, catalogues or memoirs, except as footnotes or brief acknowledgements. Enisskillen amassed a collection of 10,000 specimens, mostly collected by others, all identified and catalogued (mostly by others), that he eventually sold to the British Museum in 1883. Despite his general absence from actual scientific dialogue, he was admitted on the strength of his collecting as a Fellow of the Royal Society and the Geographical Society, elected as Vice-President of the Geological Society of Dublin (1839-1864) that morphed into the Royal Geological Society of Ireland (1865) of which he was its first president, plus was awarded law doctorates by the universities of Dublin, Durham and Oxford. Enesskillen’s collection is certainly important but contributors like Eliza Gordon Cumming received scant mention.

William Buckland was well known for his negative views concerning the role of women in science. In his 1841 address as president to the Geological Society of London, he thanked Lady Gordon Cumming for donations of Old Red Sandstone fishes to the society’s museum, acknowledging her “zeal and liberality”. The Lady wasn’t present to hear this because women were not permitted by the Society to attend such meetings. However, Buckland devoted far more ink in acknowledging all the scientists that had benefited from her generosity (M. Orr, 2021, op cit.).

Eliza Gordon Cumming died on April 21st 1842 from complications during child birth – she was only 47. Buckland’s earlier description of her “zeal” was certainly an understatement given that the pregnancy was her 13th. In 1844 Louis Agassiz wrote fulsomely about the value of her contributions to science, noting that he “must accord the foremost place to what Lady Gordon Cumming has undertaken to illustrate this ancient fauna…”, continuing “it pains me to think that this noble Lady will no longer be able to receive in person the tribute she so justly merits of the recognition of geologists.” (Quoted in M. Orr, 2021 op cit.). One can only wonder what that “tribute” might have been, but it certainly did not include anything like co-authorship in his catalogues of fossil fish, or access to the vaunted halls of science.

Agassiz had this to say about Eliza’s paleontological expertise in his Monograph on the fossil fishes from the Old Red Sandstone (p. VII):

“Among the recent contributions which have most increased our knowledge of the fossil fish of the Devonian system, I must place at the forefront what Lady Gordon Cumming did to illustrate this ancient fauna. Not content with collecting and distributing to geologists, with unparalleled liberality, the numerous copies of this precious debris that she had collected in a quarry exploited for this purpose, she studied them carefully, set aside the most perfect examples, and painted them with a precision of detail and an artistic talent that very few naturalists have been able to achieve.”

Like so many woman naturalists or scientists of the day, Eliza Gordon Cumming’s “zeal”, “liberality” and ingenuity were relegated to a kind of domestic role – not unlike all those wives of scientific husbands who were thanked for their assistance, but in reality were as productive and creative in their pursuits of science, in some cases even more so than their celebrated and medaled partners.

References and other documents

Earl of Enniskillen, 1837. A Catalogue of Fossil Fish in the Collections of the Earl of Enniskillen & Sir Philip Grey Egerton, Bart. Chester, J. Seacombe, 3pp. online: .

Earl of Enniskillen, 1841. A Catalogue of Fossil Fish in the Collections of the Earl of Enniskillen & Sir Philip Grey Egerton, Bart. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History. vol. 7, 487-498, 12 pp. PDF

Louis Agassiz, 1844, Monographie des poissons fossiles du vieux grés rouge: ou système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie (text only).

J.W. Clark and T. McK. Hughes, 1890. The Reverend Adam Sedgwick. Volume II. The Cambridge University Press. Biodiversity Heritage Library.

C. V. Burek and B. M. Higgs, 2020. Celebration of the centenary of the first female Fellows: introduction. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 506.

Mary Orr, 2021. Collecting Women in Geology: Opening the International Case of a Scottish ‘Cabinétière’, Eliza Gordon Cumming (1815-1842). In: C. V. Burek and B. M. Higgs, Celebrating 100 Years of Female Fellowship of the Geological Society: Discovering Forgotten Histories. Geological Society of London,

James Ormiston, 2021. Scotland’s Lady Of The Devonian. The Bristol Dinosaur Project, University of Bristol.

Adelene Buckland, 2024. Women Geologists 1780–1840: Re-reading Charlotte Murchison. In: E. Aronova et al. (eds.), Handbook of the Historiography of the Earth and Environmental Sciences, Historiographies of Science.

History of Scientific Women: Eliza Maria GORDON-CUMMING.

1 thought on “Eliza Maria Gordon Cumming (1795-1842)”

Pingback: Celebrating Women’s History Month: Eliza Gordon-Cumming – CCSU Geology Rocks