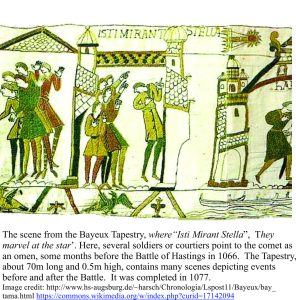

Omens, God’s wrath, or just plain misfortune; comets were seen by our Medieval forebears as a disturbance in the natural state of the heavens, portending disaster, pestilence, or famine, and if you were really unlucky, all three. Harold, Earl of Wessex and later King, before he did battle against William of Normandy in 1066, must have had some misgivings with Halley’s comet  nicely lighting up the northern sky (we now know it was comet Halley); he probably should have kept both eyes on the battle. Portent indeed; the Norman conquest changed irrevocably the history of Britain.

nicely lighting up the northern sky (we now know it was comet Halley); he probably should have kept both eyes on the battle. Portent indeed; the Norman conquest changed irrevocably the history of Britain.

It seems that the ancient Chinese were a little more rational in their deliberations on comets – they referred to them as brush stars, and as early as 613 BC were computing approximate orbits. In fact it is ancient Chinese astronomy records that have enabled modern astronomers to confirm calculated orbit periodicities for comets like Halley.

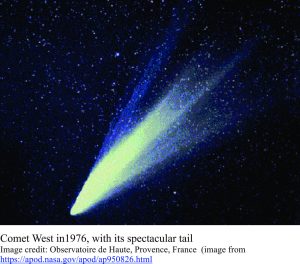

Comets are relics of a very ancient past, jettisoned by the early solar nebula during formation of our solar system about 4.6 billion years ago. Astronomers, in a nice example of theory development that awaits experimental confirmation, propose that comets occupy a vast cloud, the Oort Cloud, that surrounds the sun well beyond the Pluto’s orbit. Occasionally, these icy bits of nebula jetsam are dislodged from the cloud and propelled by gravity towards the sun. Some of these delinquent comets maintain orbits around our sun (comet Halley takes 76 years), whereas others simply pass through our solar system. They are most spectacular when they approach the sun because volatile gases and dust are jetted as tails that can extend 10 million kilometres behind the comet nucleus. From time to time, a comet’s orbit will intersect that of other heavenly bodies (including the sun). One of the more spectacular events in recent times was the July 1994 impact of Shoemaker-Levy9 on Jupiter, captured in this video (actually several impacts from fragments of the comet). The energy released on impact was outrageous.

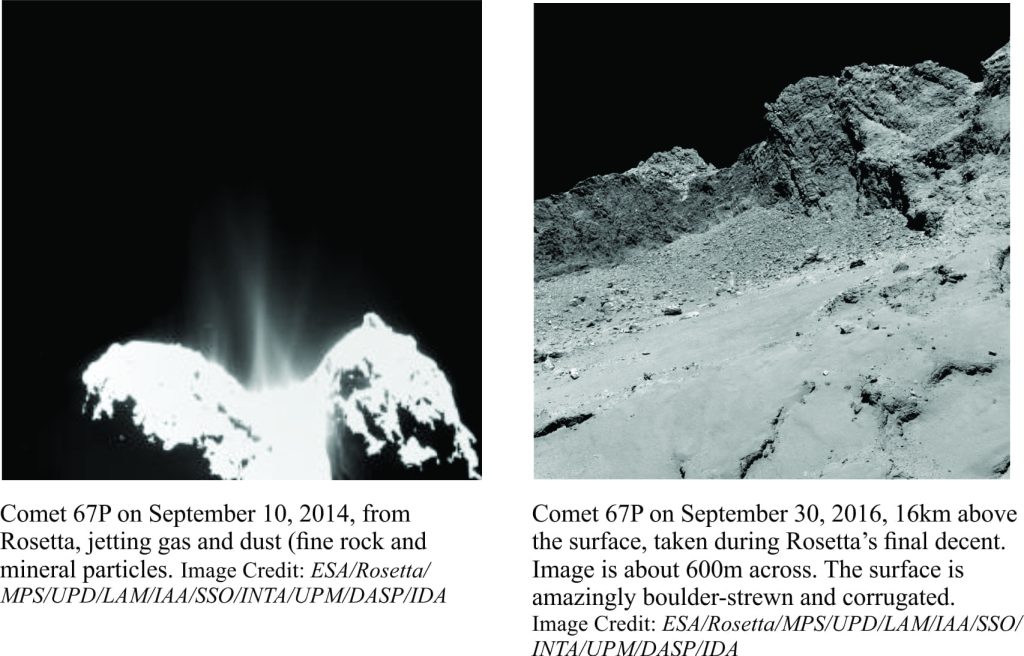

We now know quite a bit about the composition of comets, from satellites tasked to orbit through comet tails. One such ingenious mission, NASA’s Stardust, flew through the tail of comet Wild 2 in 2004, collecting dust on a specially designed silica gel. On impact, dust particles traveling at 6 times the speed of a rifle bullet, were buried in the porous gel that was designed to prevent damage or alteration. When Stardust returned to a near-earth orbit, a capsule containing the comet dust was released and collected back on earth. Stardust continued to perform other tasks. Perhaps the most startling encounter with a comet was the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission to 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Launched in 2004, Rosetta journeyed for 10 years and more than 6 billion kilometres, waking from its long hibernation in 2014, whereupon a smaller landing craft, Philae, made the first soft landing on a comet; a pretty amazing feat given the comet’s small size and distance from earth. Although Philae’s life was cut short, it did manage to operate a sniffer to collect and analyse dust at the comet surface. Analyses by both Rosetta and Philae indicate the presence of solid water-ice (expected), solid carbon dioxide (quite unexpected), phosphorous, and 16 organic compounds, some of which had not been previously detected in comets (methyl isocyanate, acetone, propionaldehyde, and acetamide), plus the amino acid glycine. They also discovered that 67P was very porous, almost fluffy rather than tightly bound rock and ice.

Perhaps the most startling encounter with a comet was the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission to 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Launched in 2004, Rosetta journeyed for 10 years and more than 6 billion kilometres, waking from its long hibernation in 2014, whereupon a smaller landing craft, Philae, made the first soft landing on a comet; a pretty amazing feat given the comet’s small size and distance from earth. Although Philae’s life was cut short, it did manage to operate a sniffer to collect and analyse dust at the comet surface. Analyses by both Rosetta and Philae indicate the presence of solid water-ice (expected), solid carbon dioxide (quite unexpected), phosphorous, and 16 organic compounds, some of which had not been previously detected in comets (methyl isocyanate, acetone, propionaldehyde, and acetamide), plus the amino acid glycine. They also discovered that 67P was very porous, almost fluffy rather than tightly bound rock and ice.

Comets are of interest, not only because of their ancestry, but because they may contain clues to the origin of organic molecules on earth, and even the origin of life.

Debate over the origin of complex organic molecules during the first few 100 million years on a young earth generally fields two schools of thought; one that postulates organic molecules, and indeed life itself originated entirely within the confines of the young ocean-atmosphere, and the other that proposes an extra-terrestrial origin, comets being prime candidates, perhaps providing the ‘organic seeds’ for further chemical reactions. There is no doubt that some important organic compounds exist on various objects hurtling through space, and they have even been detected in distant gas clouds (from spectral signals). All of these extra-terrestrial compounds have been produced abiotically (i.e. without the intervention of life forms). But it is uncertain whether any of them would have survived the fireball as comets or bits of meteorite entered the atmosphere.

The conditions during those first few eons on earth were probably conducive for the kind of home-grown organic and inorganic chemistry required to generate complex molecules; there was an atmosphere of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen and probably some sulphur dioxide (but importantly, no oxygen gas), plenty of water (fresh and saline), and UV radiation (probably no ozone). There may also have been a surfeit of hydrothermal vents (like black smokers) that are favoured by some researchers as focal points for organic evolution.

Perhaps we don’t need to invoke cometary collisions to help decipher the riddles of organic evolution on earth. Perhaps the discoveries of organic molecules on comets and other space flotsam are telling us that carbon-based chemistry is not confined to our own 3rd rock from the sun, but exists in solar systems everywhere. From that perspective, the possibility of life elsewhere seems like a logical corollary. As Mark Twain might have said, “I guess so, I dunno”.

4 thoughts on “Comets; portents of doom or icy bits of space jetsam?”

Pingback: Sverige fotbollströja

Pingback: maglia psg rabiot

Pingback: valencia drakt

Appreciate the comment