This post is part of the How To… series

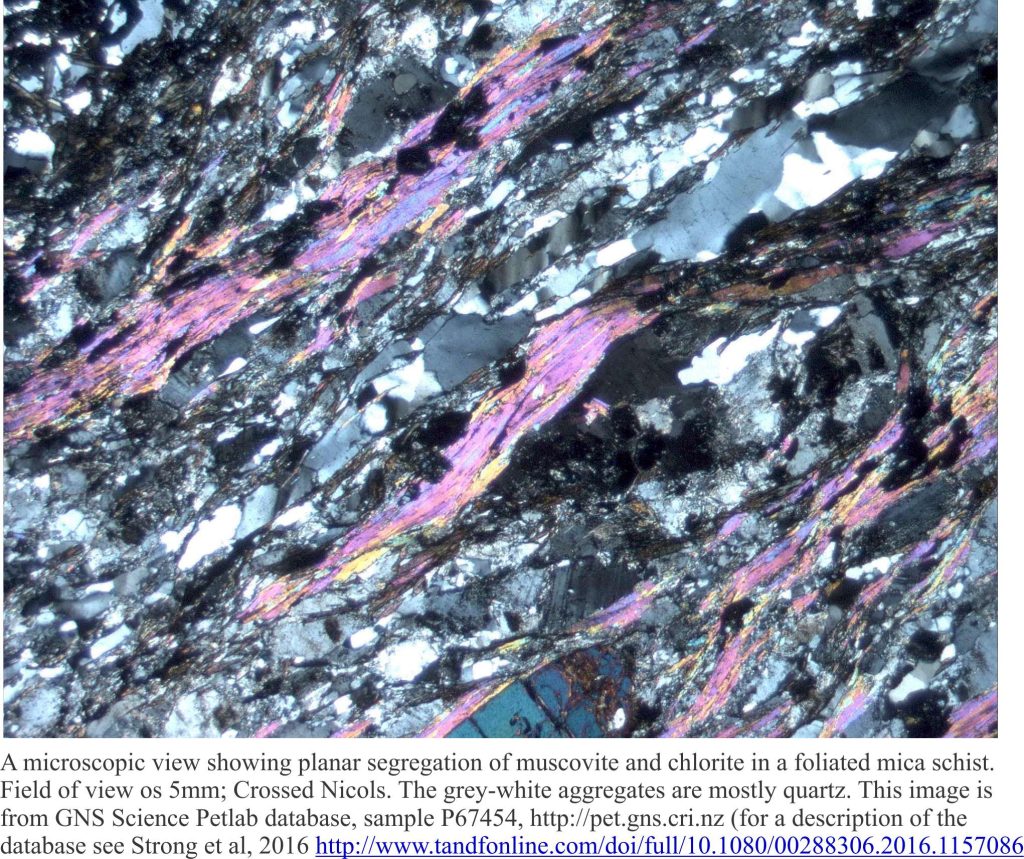

Cleavage is a fabric. It is a close, regularly spaced planar to curviplanar foliation. The term ‘cleavage’ derives from its propensity to split apart or cleave. Where cleavage is developed it is pervasive at both macroscopic (outcrop, regional map scale) and microscopic scales (thin section); in other words, it is a penetrative fabric. It is most commonly found in folded rocks that have been subjected to some degree of metamorphism – from relatively low-rank slate (slaty cleavage), to beautifully foliated schist.

Cleavage is the product of shortening and to some extent a reduction in rock volume by dissolution during folding and metamorphism. Cleavage planes are defined by an alignment of micas (hence the ability to cleave) that grow as other more labile minerals (e.g. clays, particularly illite) are recrystallized. The growth of mica crystals and progressive development of cleavage go hand in hand.

There is no void space between cleavage planes and although they are mechanically weak, the rock is continuous. Hence, cleavage differs fundamentally from joints. Joints also are regularly spaced, commonly pervasive planar structures, but they form by extension and brittle failure of a rock mass. This process results in void space, or fracture porosity that during burial will become the locus for precipitation of minerals such as calcite and quartz.

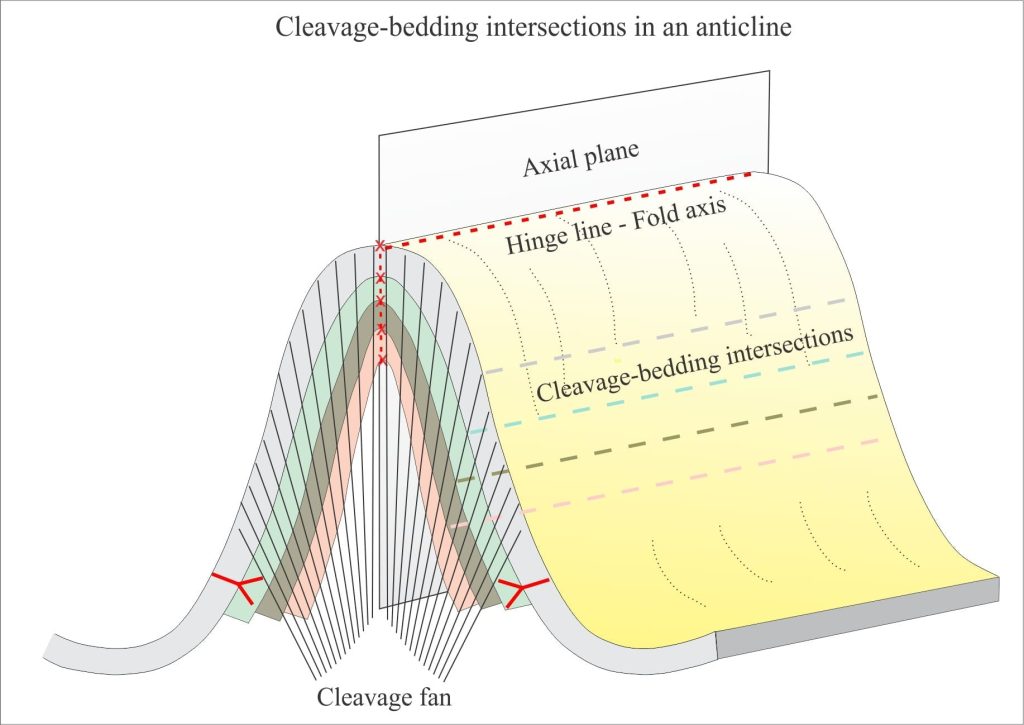

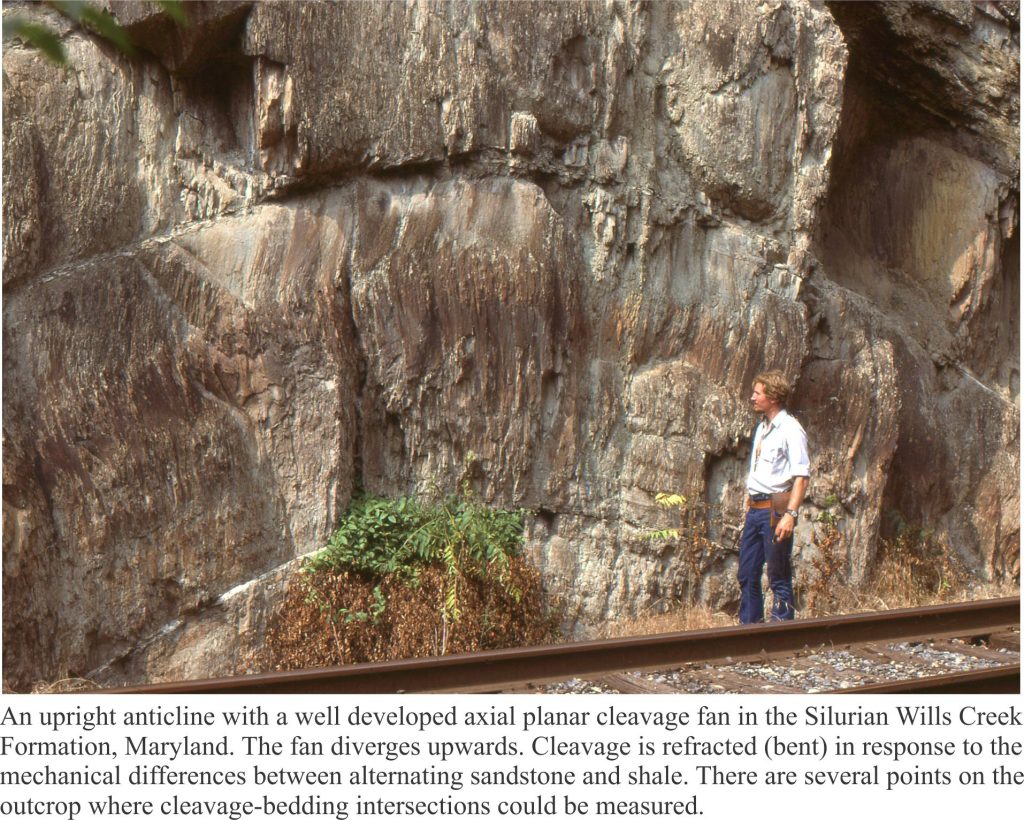

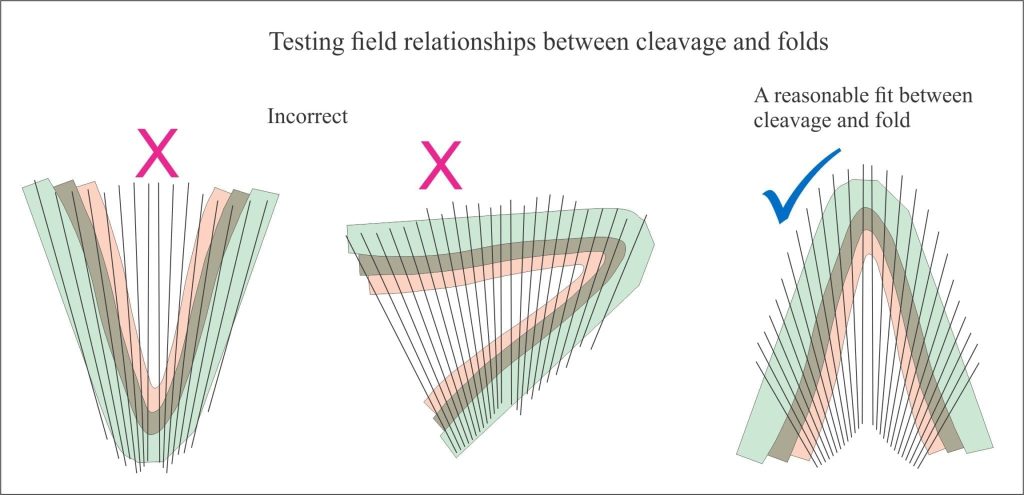

Cleavage has a geometric relationship with folds. Arrays of cleavage are commonly arranged as fans about axial surfaces and in tight folds cleavage closely parallels axial surfaces. Both cases are referred to as axial planar cleavage. Fans diverge upwards in anticlines and converge upwards in synclines. This relationship furnishes us with yet another tool for deciphering fold type and fold orientation.

- The intersection of a cleavage plane with bedding creates a lineation that is parallel to the fold axis. We can measure its trend and plunge.

- In upright folds, cleavage planes have dips steeper than bedding. Cleavage plane dip in overturned and recumbent folds may be less than bedding dips – if you observe this geometric relationship in outcrop then consider the possibility that the folds are overturned (S and Z parasitic fold orientation will be useful in this regard).

- Cleavage geometry can be used to determine the facing direction of beds such that we can go beyond an antiform-synform description and identify more specifically anticlines and synclines. A simple example is shown in the cartoon below.

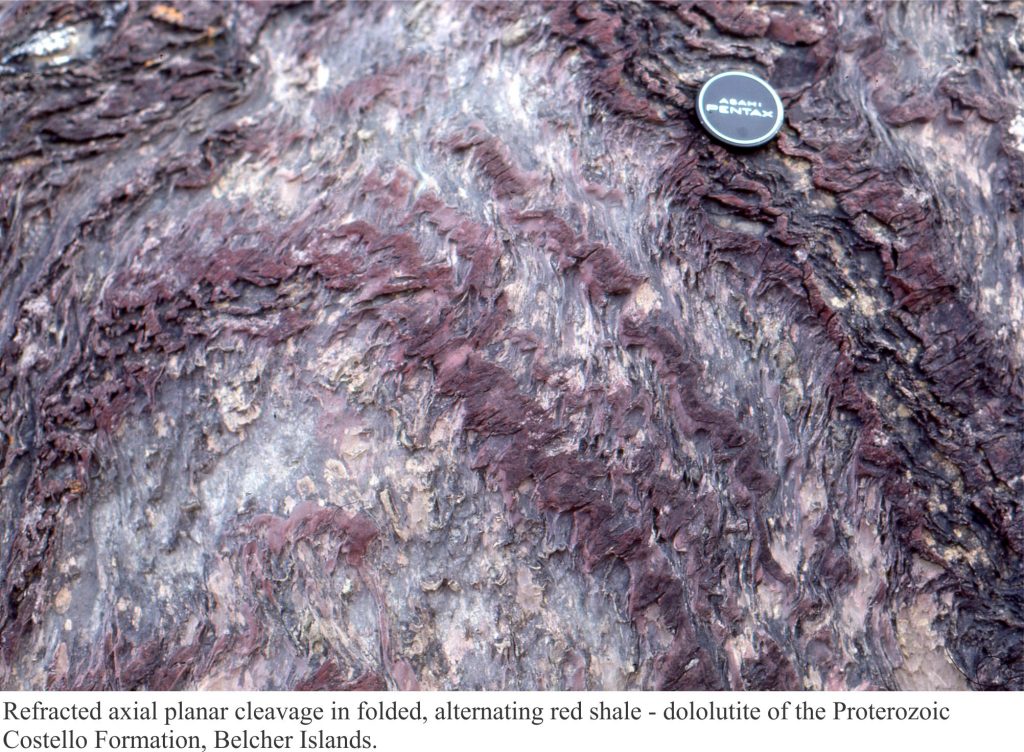

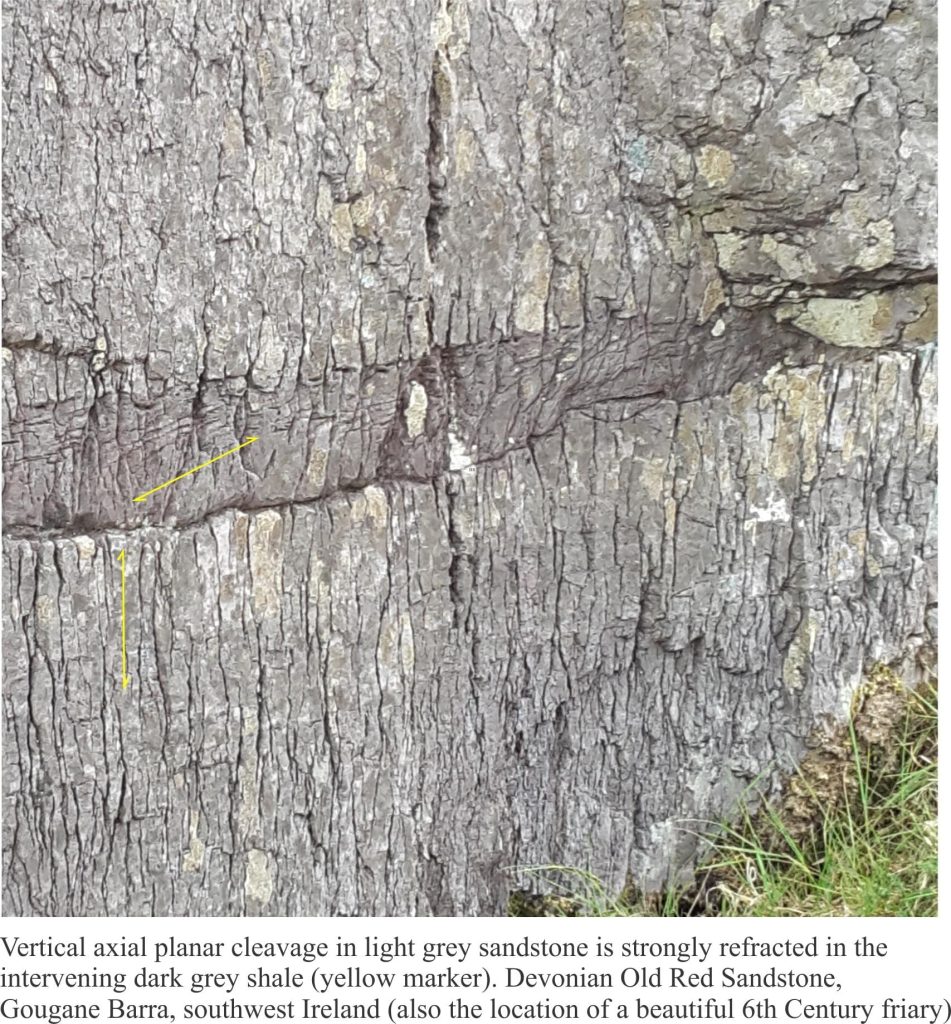

Cleavage is not always uniformly planar. In layered successions cleavage planes are commonly refracted or bent. The change in orientation reflects how different lithologies respond to stress; common examples of cleavage refraction occur in successions of alternating sandstone (mechanically strong) and shale (mechanically weaker). A couple of examples are shown below.

Other useful links in this series: