How bits of ancient North America (Laurentia) were left behind in the Scottish Hebrides.

The jigsaw puzzle of continents and oceans, the ground beneath you, the seas beyond, even the weather you enjoy or endure, are governed largely by plate tectonics. This grand mechanism creates plates along mid-ocean volcanic ridges, then proceeds to push them down the throat of subduction zones. Plates collide, tearing at each other’s crust. Volcanic hiccups, earthquakes, and crustal dismemberment are all part of a tectonic plate’s stressful life. And occasionally in this mad nihilist rush (after all, millimeters per year is pretty quick), bits are left behind.

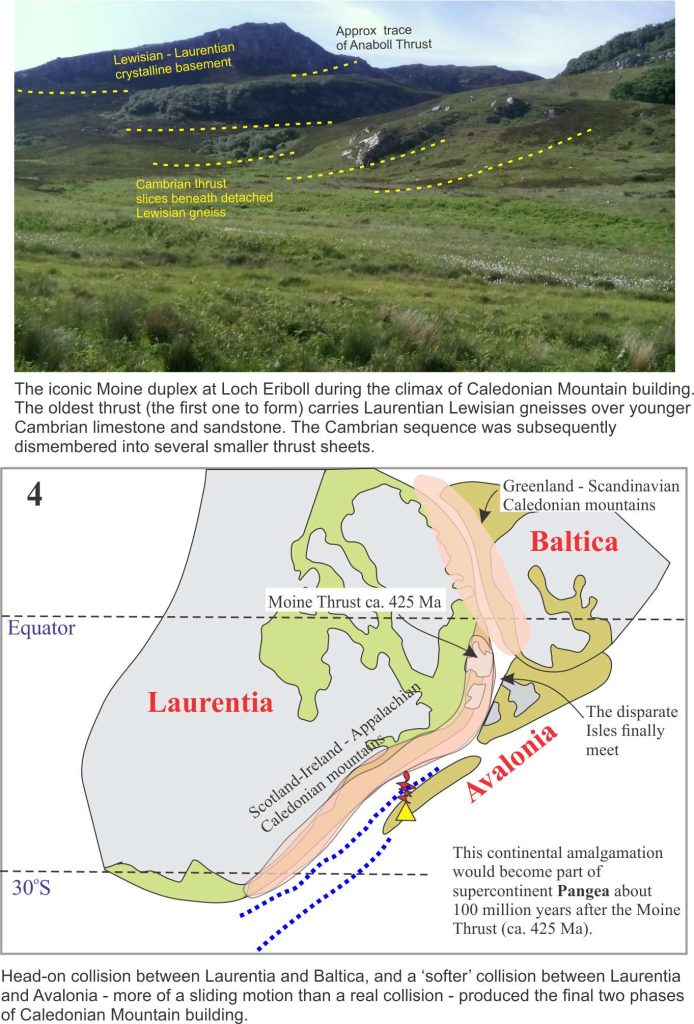

The landscapes of north Scotland and northwest Ireland are underpinned by rocks that once belonged to North America, or at least an ancient version of it. As geological puzzles go, they are iconic; here James Hutton unraveled the problems of deep time, and Peach and Horne sliced the ancient crust into moveable slabs. The rocks are part of the Caledonian Orogen, a mountain chain that formed from tectonic plate collisions more than 400 million years ago, stretching from Scandinavia to Scotland-Ireland, east Greenland, and the Appalachians of eastern USA and Canada.

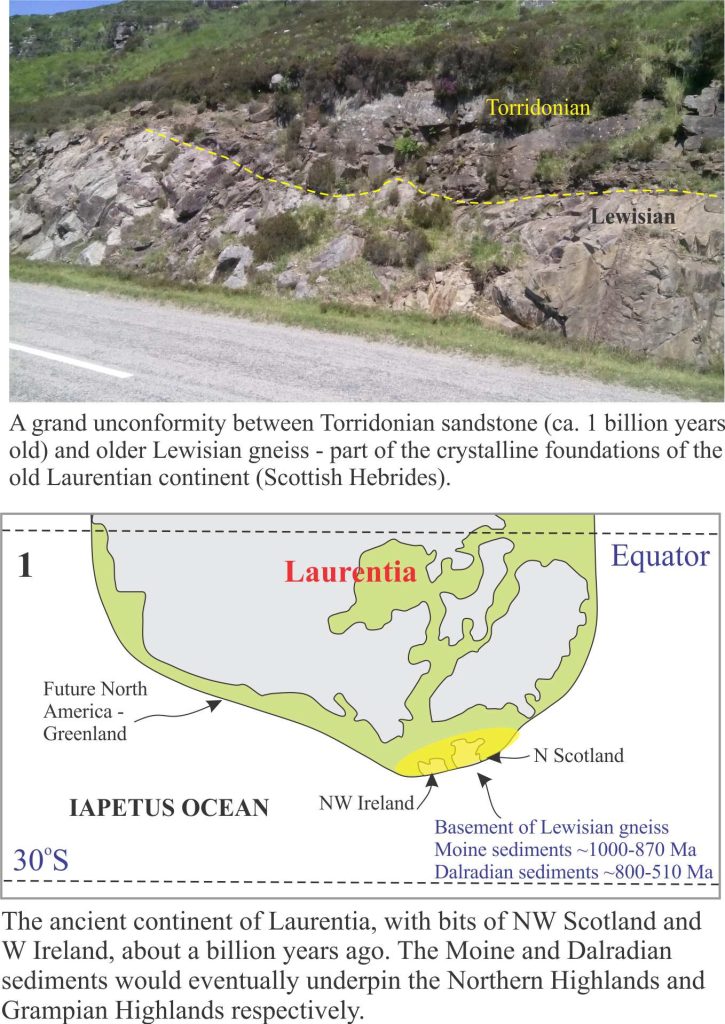

The choice of a starting point for a story like this is a bit arbitrary because continental and oceanic plates, and the plate tectonic mechanisms that propel them across the globe, date back at least one billion years, possibly earlier. For convenience, this tale begins on the ancient continent of Laurentia about a billion years ago; Laurentia was an amalgam of North America, Greenland, and (what would become) north Scotland and northwest Ireland tucked along its eastern margin [The first four figures here are modified from an excellent technical summary of this important period in Earth’s history, by David Chew and Rob Strachan, their Figure 1, in Geological Society of London, Special Paper 390, pages 45-91, 2014].

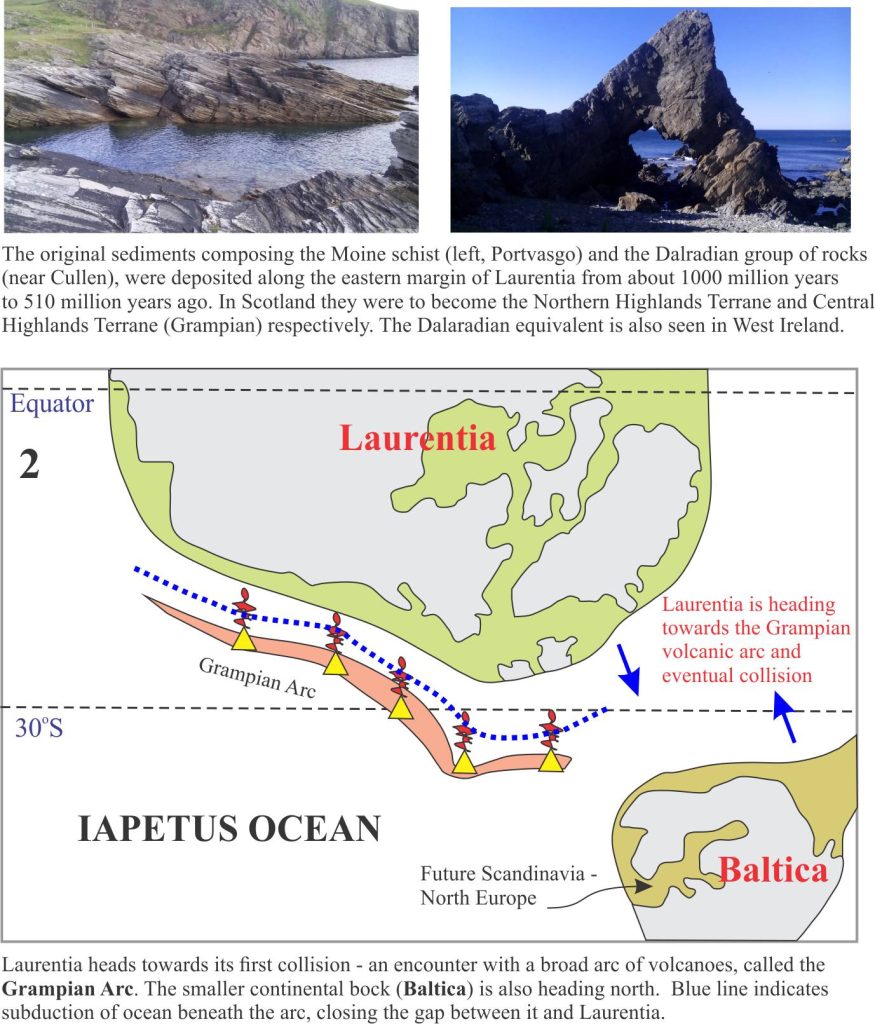

Three groups of rock that underpin the Scottish Highlands, originally formed along the eastern Laurentian margin. Lewisian gneisses. Some as old as 2.7 billion years, were part of the basement foundations of Laurentia (Panel 1 above). Two major groups of sedimentary rock were also deposited along the eastern margin – the Moine group of rocks, that beneath the Northern Highlands we now see as metamorphic rocks, originally formed as sediment shed from the ancient continent about 1000 to 870 million years ago. Dalradian metamorphic rocks that now form the Grampian Highlands also originated as sediments and volcanics from about 800 to 510 million years – metamorphism occurred much later.

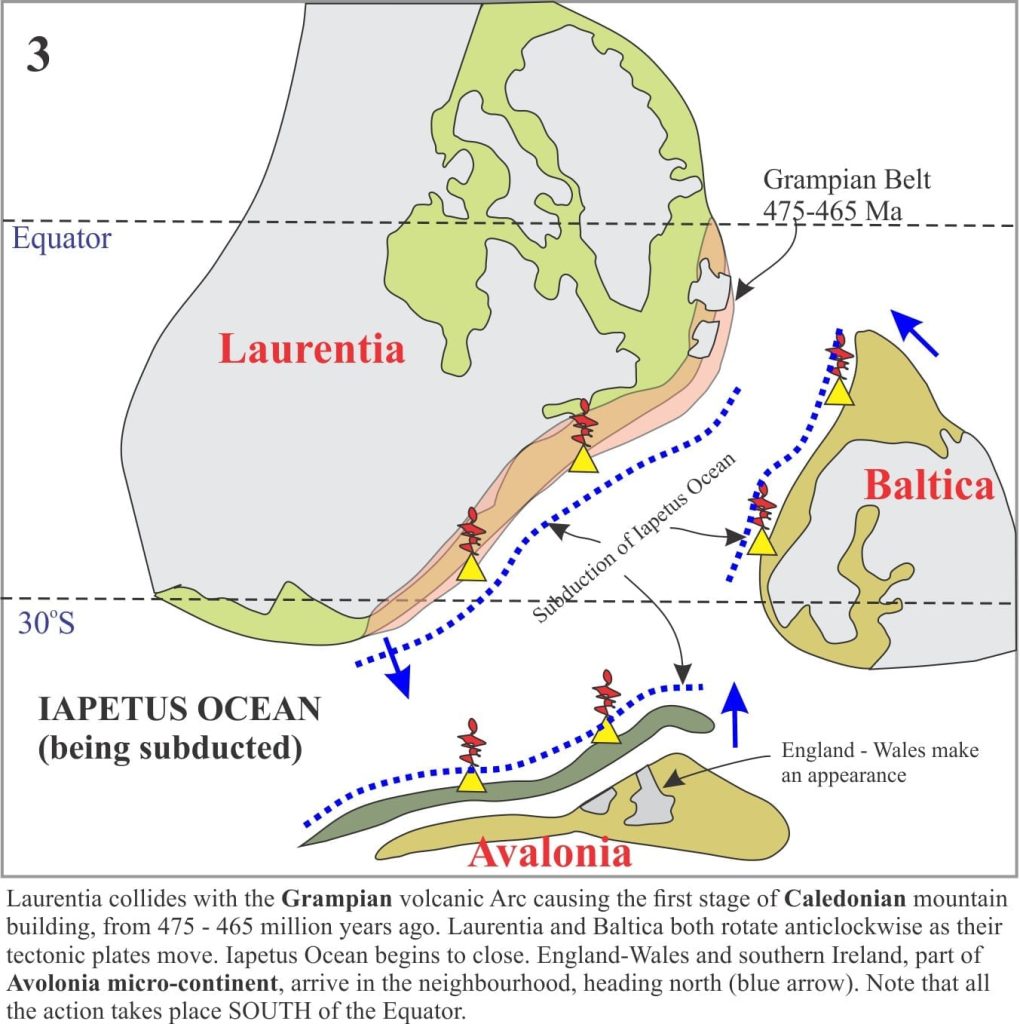

For the next few million years Laurentia moved south (south of the Equator!) towards, it is hypothesized, a volcanic arc, similar perhaps to modern Ring of Fire volcanic arcs that rim the Pacific Ocean (Panel 2). Collision between Laurentia and the Grampian Arc initiated the first phase of Caledonian mountain building 475-465 million years ago (Panel 3).

Several other events were also taking place at this time. Laurentia itself was rotating anticlockwise. Two smaller continental plates appeared on the scene: Baltica (that would later become Scandinavia and north Europe), and Avalonia (whence the rest of England, Wales and south Ireland resided), both were migrating north towards Laurentia. The intervening ocean, the Iapetus, was gradually shrinking as its crust was devoured down at least three subduction zones (Panel 3).

The Iapetus eventually closed; some slivers of oceanic crust (called ophiolites) were scraped off and incorporated into the Caledonian mountain complex, but most of this once-grand ocean basin was consumed in Earth’s grand recycling depot.

Baltica and Laurentia were involved in head-on collision around 435-425 million years (Panel 4). The Moine thrust, one of the defining ‘moments’ of tectonic dislocation and metamorphism in the Caledonian, developed during this interval. In contrast Avalonia’s approach was more oblique and it appears this smallish continental fragment slid past Laurentia. Avalonia’s legacy is that south England, Wales and south Ireland were now stitched firmly to their northern cousins. This plate tectonic assemblage has withstood tempests, bolides, and glaciations for the last 400 million years; 2000 years of geopolitical ructions are insignificant in comparison.

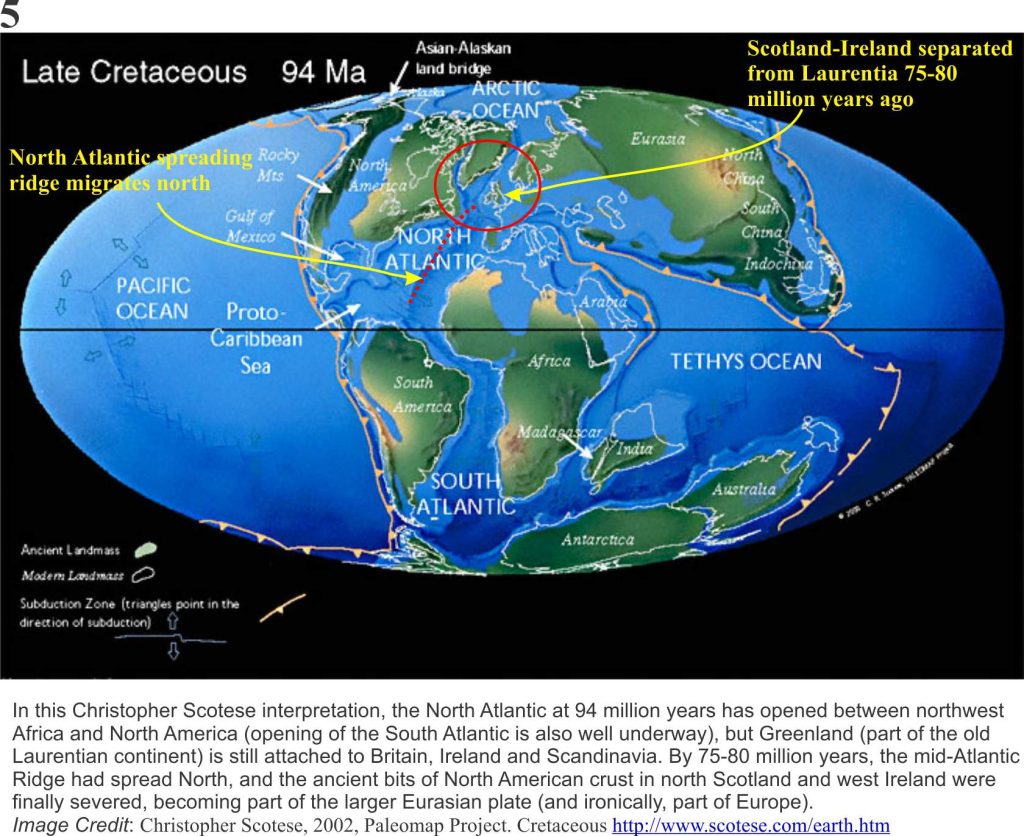

The amalgamation of Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia eventually became part of a much larger continental mass, a super continent called Pangea that included Africa, South America, Antarctica, Australia and Asia (and of course, New Zealand). This amalgamation was well underway 335 million years ago. Pangea began to break apart about 175 million years ago, a separation that over the next 175 million years would give us our most recent plate tectonic configuration of ocean basins and continents (Plate 5). Break up of Pangea took place in several stages, but the event that is of interest here took place about 75-80 million years ago. [Chris Scotese has created an excellent animation of these events, set to nice music].

Atlantic Ocean had its beginnings during the early stages of Pangea break up, 175 million years ago. Atlantic Ocean’s expansion is centered along a submarine spreading ridge of volcanism (that today stretches from Iceland almost to Antarctica). The spreading ridge migrated northwards, which means that new ocean floor was also being created incrementally northwards. During the early stages of North Atlantic Ocean expansion, the British Isles were still firmly attached to the old Laurentia margin. But by 80 million years the locus of spreading had moved west of Britain and Ireland (Plate 5), and it was at this point that the ancient roots of north Scotland and Ireland became divorced from North America and Greenland – a decree absolute.

The period of Caledonian mountain building is one of the most studied in the geological community (at least two centuries worth, and 100s of 1000s of scientific papers), much of it undertaken before plate tectonics was discovered in the mid-1960s. Nevertheless, plate tectonics theory has provided a more global context, and a more rational, mechanistic approach to solving the myriad geological complexities.

I recently visited some of these rocks in the Scottish Hebrides and Connemara – and yes, there is complexity at every level of observation. The story I have presented is simplified – perhaps woefully so. But even a simple rendition can promote understanding. I’d like to think so.

2 thoughts on “Bits of North America that were left behind”

Hi. What are your sources when describing the paleolatitudes of Laurentia and Northern Scotlands placement in Laurentia? Thank you.

Hi, Most of the info for the diagrams (not the photos) was from Chew and Strachan The Laurentian Caledonides of Scotland and Ireland

February 2014 Geological Society London Special Publications 390(1) – you can download this from Reseachgate if you have no institutional access