By the early 1970s, the new tectonics (the plate kind) had established a firm grip on the geological consciousness. Even sedimentologists and stratigraphers were extricating themselves from the vagaries of geosynclines and interminable arguments about Formation boundaries, to begin exploring sedimentary basins in terms of plate dynamics. As an undergraduate student at the time, the excitement was palpable. Instead of thinking about sedimentary basins as nebulous eugeosynclines or miogeosynclines for which modern analogues were few and far between, we could now establish rational models based on actualistic examples from convergent, divergent, and strike-slip plate boundaries.

Strike-slip zones are rarely defined by a single fault strand along which slip is purely strike-parallel. They tend to be far more complex, where oblique stress vectors produce transtensional and transpressional strain that includes normal and reverse/thrust faults, en echelon folds, structural pop-up ridges, and block rotation. In fact, strain can be distributed across several structural domains. For example, the effects of transpression along the San Andreas transform are partitioned across a zone 500 km wide, that includes the Transverse Ranges and part of the Basin and Range Province (Atwater, 1970).

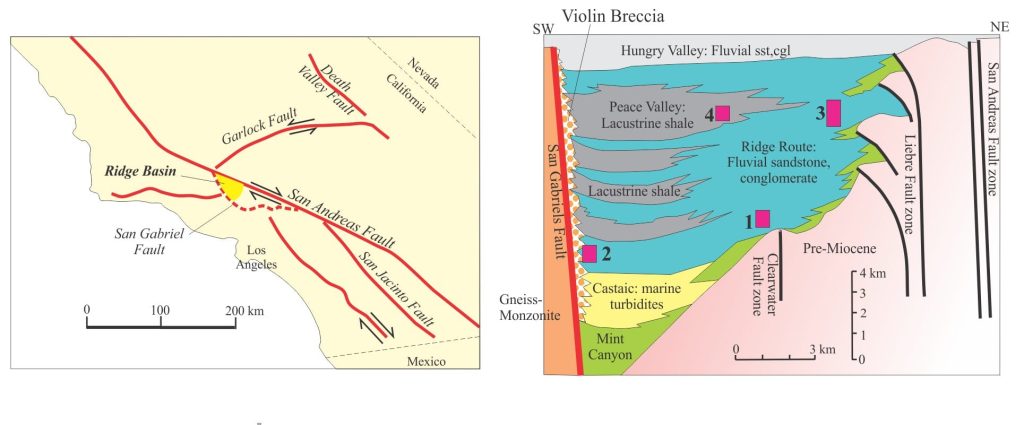

The structural diversity across strike-slip faults also means that basins can form pretty well anywhere there is extension-related subsidence: releasing bends, fault oversteps, curved lateral ramps, and transfer faults. John Crowell’s 1974 paper on releasing bend basins associated with the San Andreas transform has been our constant guide to understanding the interplay among sedimentation, stratigraphic architecture, and active strike-slip faulting. There are several variations subsequent to the model he proposed but the basics of his insights still stand. One of the examples he focused on, the iconic Middle Miocene – Pliocene Ridge Basin located in the Transverse Range rotational block, illustrates nicely the structural and stratigraphic complexities of strike-slip basins – these are summarized below (Biddle and Christie Blick, 1985; May at al, 1993 ; Crowell, 2003; Link and Crowell, 2003; Allen and Allen, 2005, 2013. A 1980 IAS Special Publication on strike-slip basins by Peter Ballance and Harold Reading also contains some great papers.

Following this summary, and by way of contrast, some basins associated with the marine portion of Alpine Fault (Aotearoa New Zealand) will be outlined.

Lessons from Ridge Basin

Basins formed by extension:

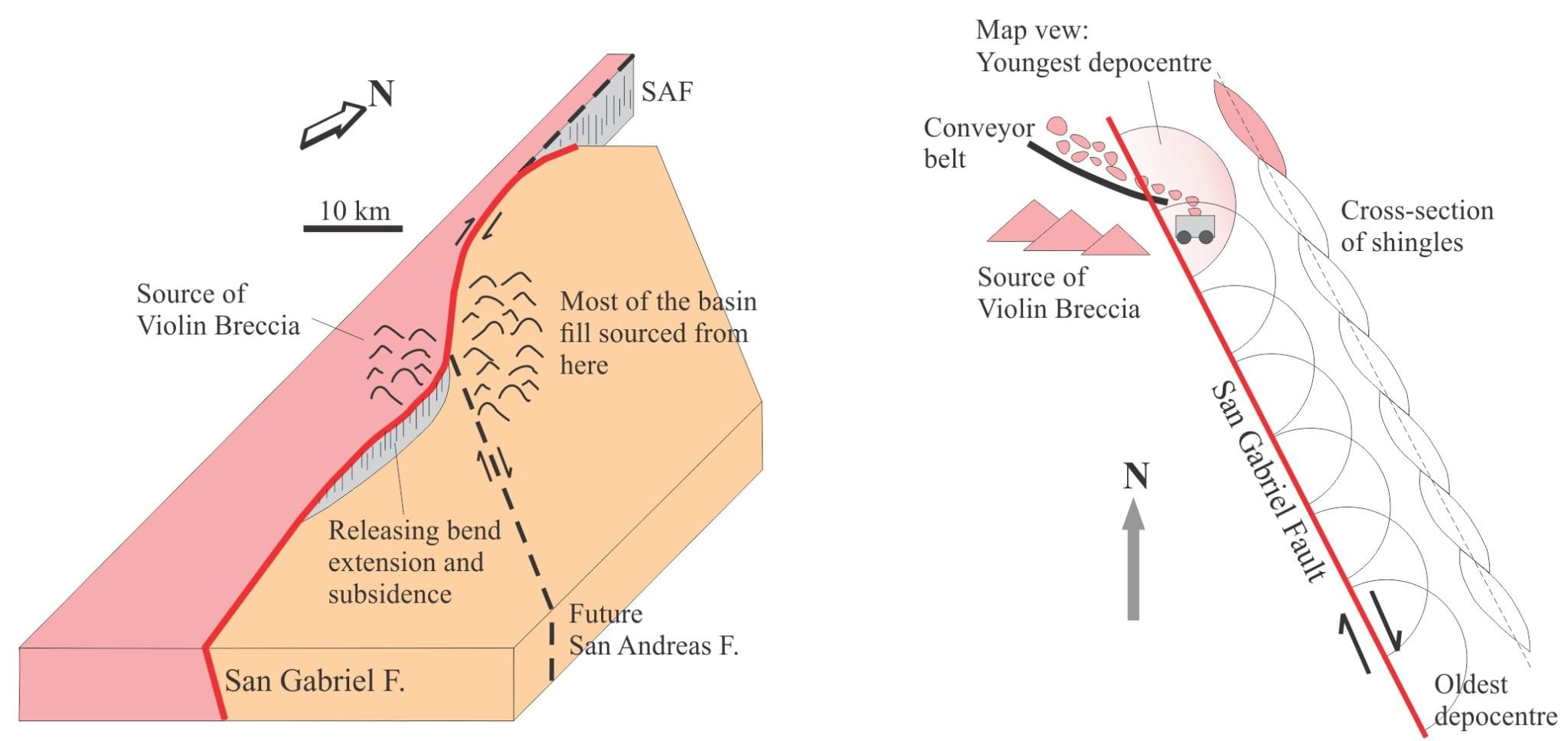

Ridge Basin formed at a releasing bend of the right-lateral San Gabriel Fault, beginning about 11 Ma and terminating 4 Ma. San Gabriel Fault in the Transverse Ranges (southern California) was an active strand of the ancestral San Andreas transform; right-lateral displacement switched to the modern San Andreas fault about 5 Ma. Uplift and dissection of Ridge Basin began about 4Ma.

Basin shape and aspect ratio:

Strike-slip basin shapes (in map view) range from almost rectangular through rhomboidal, to spindle and sigmoidal. Ridge Basin was narrow ~ 5-10 km, about 40 km long, but capable of accommodating great thicknesses of sediment; it had high aspect ratio (length to width) compared with basins like passive margins and foredeeps. Presently active strike-slip basins have similar dimensions: Dead Sea basin along the transform boundary between the African and Arabian plates is 132 km long, up to 18 km wide, and contains about 10 km of sedimentary fill (Allen and Allen, 2005); Several basins that are presently active at releasing bends and stepovers along the southern, offshore Alpine Fault (Aotearoa-NZ), are as little as 2-3 km wide but have aspect ratios of 10 and more (Barnes et al. 2005). Basin shape and aspect ratio are expected to change over the life of strike-slip basins in concert with continued deformation along the bounding fault, and any subsidiary contemporary structures that may develop. Continuous deformation will have a major influence on stratigraphic architecture and sediment composition.

Cross-section profiles

Basin profiles are commonly asymmetric. Ridge Basin has a distinct half- graben geometry defined by San Gabriel Fault along the southwest margin. Faulted margins will be the site for alluvial fans and talus fans. Elsewhere, strata will onlap the basin floor and the relatively shallow-dipping margin opposite.

Stratigraphic thickness:

In many strike-slip basins, the total stratigraphic thickness is high compared with the overall basin size. In Ridge Basin, this total is about 14 km! Sedimentation rates were also high. One of the more important discoveries by Crowell, Link, and others was that this great thickness is not accommodated at any one location but is the cumulative thickness of multiple stratigraphic packages. For Ridge Basin, these packages occur in a regular northwest-dipping and northwest younging succession. The evidence for this is found in a remarkable stratigraphic unit – the Violin Breccia.

Rejuvenated faulting:

Violin Breccia was deposited at the base of the continuously active San Gabriel Fault, mainly as talus fans, debris flows and sheet floods. It maps a total of 33 km along fault strike, but only extends 1-2 km towards the basin axis; breccia beds dip about 20o. Despite its limited lateral extent, its cumulative thickness is about 11 km. Its composition is distinctive – gneiss, amphibolite, and quartz monzonite, composing poorly sorted breccia and finer-grained interbeds. Many fragments exhibit shearing. Violin Breccia interfingers basinward with marine, lacustrine, delta and fluvial deposits in successively younger formations throughout the 11,000 m succession, indicating that the fault scarp must have been reactivated many times during its 6 million year lifespan. Crowell surmised that deepening of the basin occurred concomitantly with fault rejuvenation (releasing bend extension) and that successive episodes of faulting resulted in (relative) northward migration of the basin depocenter – he used the analogy of a conveyor belt dumping material into successive train wagons.

Stratigraphic shingling:

The conveyor belt analogy applies not only to the Violin Breccia, but to the entire basin. Migration of the basin depocenter during “tectonic pulses” produced successive, northwest-dipping stratigraphic packages that onlapped the basin floor, stacked like roofing shingles. At any one location the thickness of overlapping shingles might be measured in 100s of m; the cumulative thickness, along the northwest-trending Ridge Basin axis was 14,000 m. Crowell’s shingling model was probably the most important contribution to our understanding of strike-slip basin subsidence and stratigraphic accommodation.

Lessons from some New Zealand strike-slip basins

In the following summary, the key points of difference to Ridge Basin include:

- The NZ basins occur at the transition from transform to subduction boundaries.

- They are fully marine, at depths of 3000 m, and fed primarily by glacial-derived sediment during the last glaciation.

- Sediment routing is via gullies, canyons, and submarine fans, and

- Using Dagg Basin as an example, different segments of some basins may undergo simultaneous extensional subsidence and contractional inversion.

Basins at a transform-subduction transition:

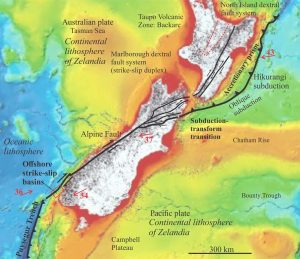

Alpine Fault is a single strand or zone of deformation through central and southern South Island. At its northern extent, strain is distributed across several right-lateral strike-slip faults (Marlborough fault splay) that extend across Cook Strait into North Island and the offshore transition to the Hikurangi subduction zone.

At its southern extent, Alpine Fault extends 230 km offshore Fiordland, whereupon it links with the principal thrust of the Puysegur subduction zone (where the Australian plate is thrust beneath the Pacific plate (note that this is the opposite subduction polarity to the Hikurangi subduction zone where Pacific plate is the lower plate). The relative motion of the Australian Plate diverges up to 25o from Alpine Fault strike; the resulting strain is distributed across a 10-20 km wide zone of mechanically linked fault segments; most of these faults have right-lateral displacement. The strain is further partitioned into a series of strike-slip basins and pop-up ridges. The Alpine Fault zone also lies landward of a subduction accretionary wedge.

Some strike-slip faults controlled by pre-existing structural fabrics:

Reactivation of faults in older basement and orogens is relatively common; this has been observed on many occasions in extensional, contractional, and strike-slip tectonic settings. Barnes et al. (2005) have surmised that Eocene, rift-related faults in the Australian plate, may have been reactivated as the southern extension of Alpine Fault.

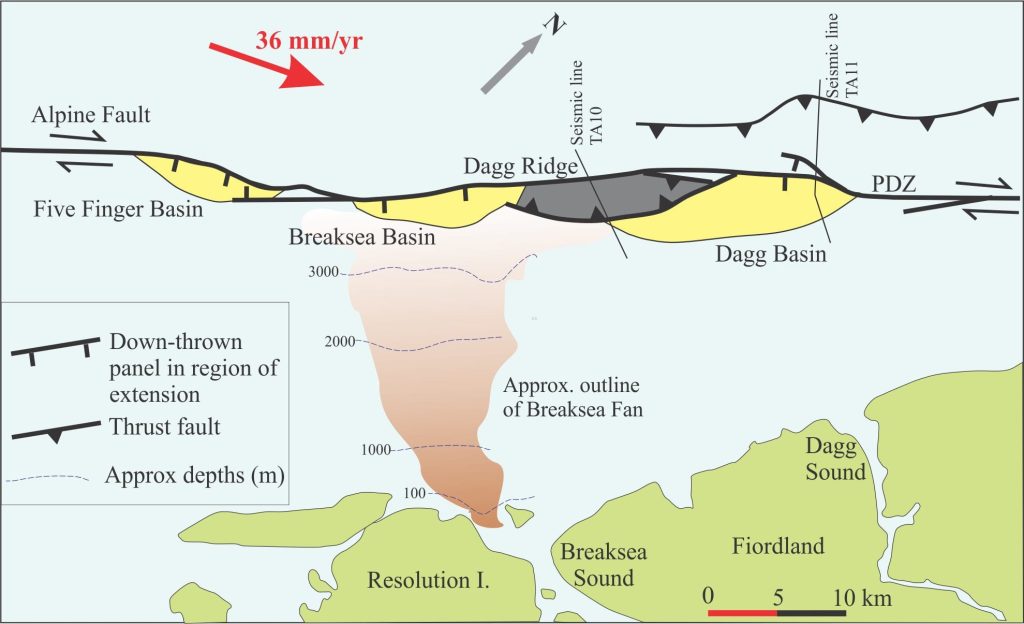

Basins at releasing bend – stepover extension:

The principal strands of southern offshore Alpine Fault are connected by releasing bends, mostly right-stepping, and right-handed stepovers. The basins occur at an average 3000 m water depth. They have bathymetric and seismic expression as half grabens bound by master faults on their west-northwest margins. Most basins are associated with negative flower structures. Contractional pop-up ridges at restraining bends or stepovers are bound by steep normal faults and thrusts that in seismic profiles have positive flower structure geometries. Basin lengths range from 7.4 to 34 km; aspect ratios from 3.2 to 12.6.

Simultaneous extension and contraction in Dagg Basin:

(The information here is from Barnes et al, 2001 and 2005).

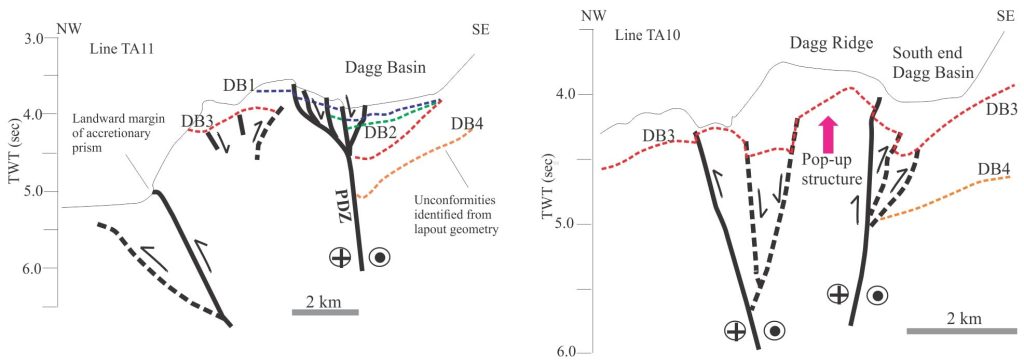

Dagg Basin is an extensional, right-handed releasing bend depocenter about 25 km long. Faults at the north end of the basin are arranged in a negative flower (tulip) structure, but the relative vertical displacement appears to change towards the southern end where fault splays have reverse-slip. The basin merges southwards into a contractional ridge (Dagg Ridge). Breaksea Basin, south of Dagg Ridge, is morphologically and structurally linked to the ridge and Dagg Basin.

Barnes et al (2005) have identified 4 unconformities in the basin fill that at its northern end onlap eastward the older bedrock; the two oldest (DB4, DB3) have pronounced angular discordances. DB3 is estimated to be 30,000-110,000 years old. Strata overlying DB3 are therefore latest Pleistocene to Holocene. Farther south, unconformity DB3 and overlying strata have been uplifted along Dagg Ridge. Thus, it appears that, while Dagg Basin is actively filling at its northern extent, it is being inverted at its southern limit by contractional faults. Both extensional subsidence and contractional uplift are considered to be contemporaneous.

Sediment routing:

Seismic profiles illustrated by Barnes et al (2005) show basin fill is discordant against the boundary faults and onlapping the adjacent margin. The most recent fill was derived from glaciated terrain to the east via submarine fans, canyons, and gullies that, during the last glaciation, had high sedimentation rates. Fiordland is the present onshore geomorphic expression of these supply routes (there was no contiguous ice cap over southern New Zealand, but the region was heavily glaciated).

Other posts in this series

Sedimentary basins: Regions of prolonged subsidence

The rheology of the lithosphere

Isostasy: A lithospheric balancing act

The thermal structure of the lithosphere

Classification of sedimentary basins

Stretching the lithosphere: Rift basins

Nascent, conjugate passive margins

Thrust faults: Some common terminology

Basins formed by lithospheric flexure

Allochthonous terranes – suspect and exotic

Source to sink: Sediment routing systems