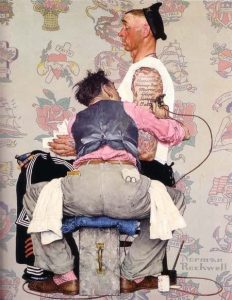

The Saturday Evening Post, March 4, 1944, featured on its cover the iconic Norman Rockwell portrait of The Tattoo Artist. The artist (a friend of Rockwell’s), his backside bulging towards the viewer, has crossed out the names of former loves and is in the process of immortalizing ‘Betty’ on the arm of a grateful sailor. The fickleness of love permanently inked on its next port of call. A simple picture at first glance, but imbued with all kinds of hidden meaning: personal goals or conquests, the lighter side of global conflict, the personal choices one makes in life and their consequences (intended or otherwise), and the role of so many different tattoo motifs as symbols, metaphors, or memories.

Tattoos have been around for thousands of years, but their introduction to western societies is relatively recent. Sailors, returning to Britain from Cook’s 18th century voyages to Polynesia, displayed adornments on various bits of their anatomy to a shocked audience. Motifs such as anchors and doves signified high seas adventures. You could measure the metal of a traveler by their inked motifs. Fast forward 250 years, and you’re more likely to discover a liking for large trucks or serpentine entwinement, a favourite cat, or perhaps the cast of Star Trek that might indicate the traveler ventured no further than their living room.

I chose an iconic New Zealand seashell, a snail, for the most mundane reason; I have stood on several specimens, embedding them in my foot. They remind me of my time on deserted beaches skirting Great Exhibition Bay, along New Zealand’s northernmost coast.

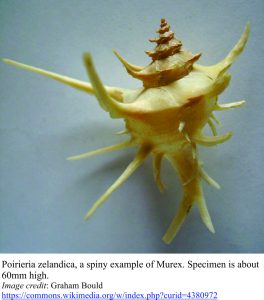

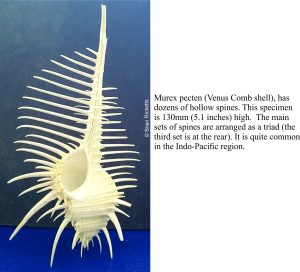

Poirieria zelandica belongs to the family of marine snails (gastropods) known as the Muricidae, commonly referred to as Murex. There are more than 1600 identified species seas-wide. They constitute some of the most ornate, spiniest shells known, including the fabulous Venus Comb Shell (Murex pecten).

Murex grow their spines for protection (including protection against marauding feet), and for support in soft sands and muds. They tend to live between 20-200m water depth. Most dine on clams or other snails (particularly those that don’t have spines). Like many marine snails, they have a built-in, tongue-like drill or rasp, called a radula, that they use to bore into hard clam shells. Some species also secrete an acid into the boring, to help dissolve the hard, calcium carbonate shell of its prey. The Murex will then suck out the juicy, clam-chowdery bits.

The New Zealand species of Poirieria can be found from one end of the country to the other, but more commonly occurs along our northern, subtropical to temperate coasts. It is not as spiny as the tropical Venus Comb shell, but it is quite robust. Empty shells, as I have discovered from time to time, lie on the beach with their longest spines upwards.

I am happy with the inked product; I made the right choice. There will be no need for crossing out or strike through. There will be no need for a replacement, no spurning of my regard for it being part of my life. All I require now is a suitable compliment, for the other arm.