Identifying detrital lithic fragments

This post is part of the How To… series

See also the companion post: Lithic grains in thin section: Avoiding ambiguity

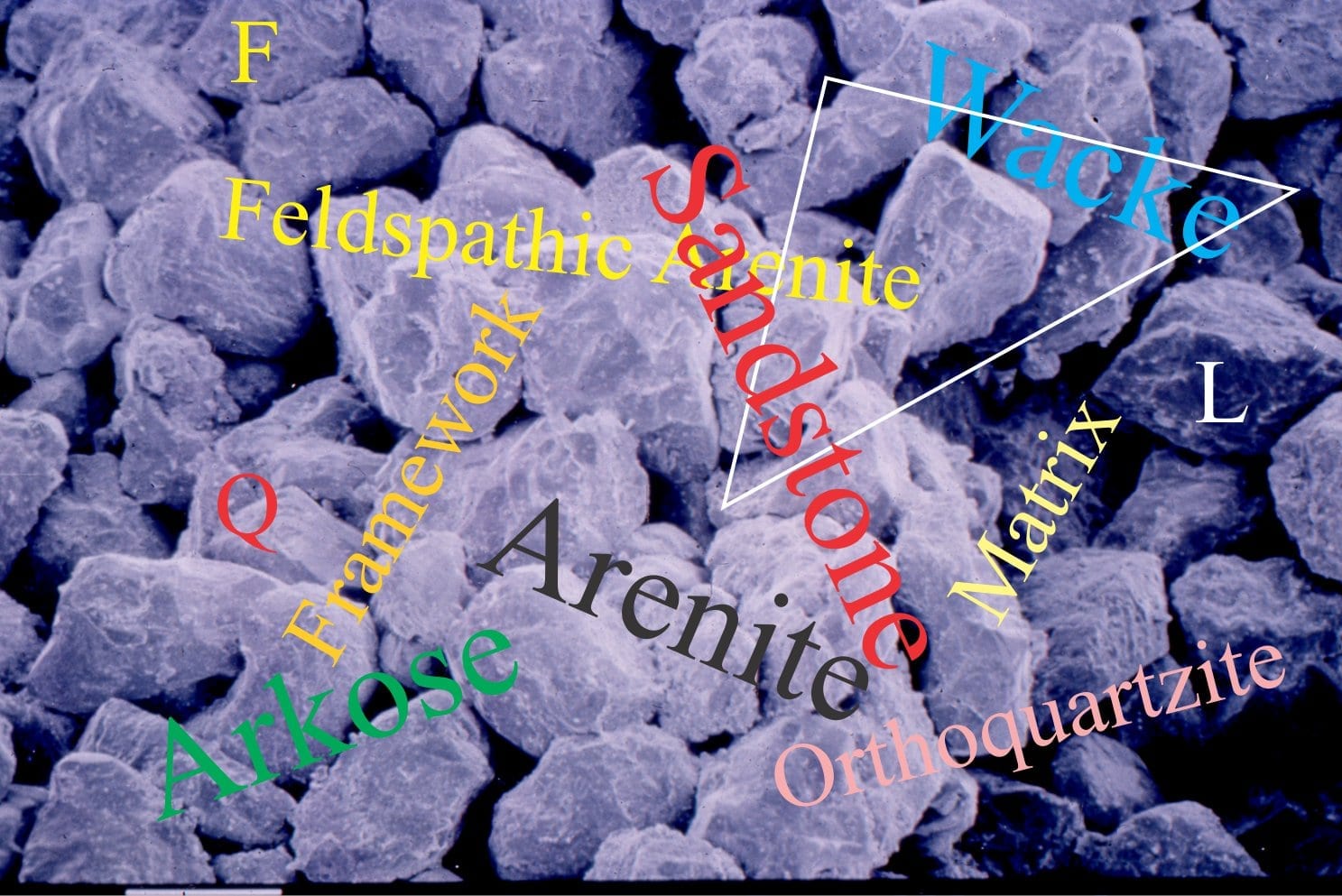

Lithic fragments are the bits of eroded or broken rock that can’t be easily slotted into either the quartz or feldspar classification end-members. They are the fragments that are not broken down into single minerals. They tend to be fine-grained and rather dirty looking in shades of brown and grey. In thin section they are nowhere near as exciting to look at as other framework grains. But If we want to know something about sediment source rocks (provenance) or the longevity and survival of granular sediment during transport and deposition, then lithics are no less valuable than quartz, feldspar – perhaps more so.

R.H. Dott’s classification divides the lithic end-member into sedimentary, volcanic, and metamorphic clasts; R.L. Folk takes each of these a step further (I’m not convinced Folk’s subdivision is practical). Part of the problem with too fine a subdivision is the diagenetic and mechanical alteration that lithics are prone to, rendering them indeterminate. Lithic fragments are much softer and chemically more reactive than their quartz-feldspar counterparts during burial diagenesis.

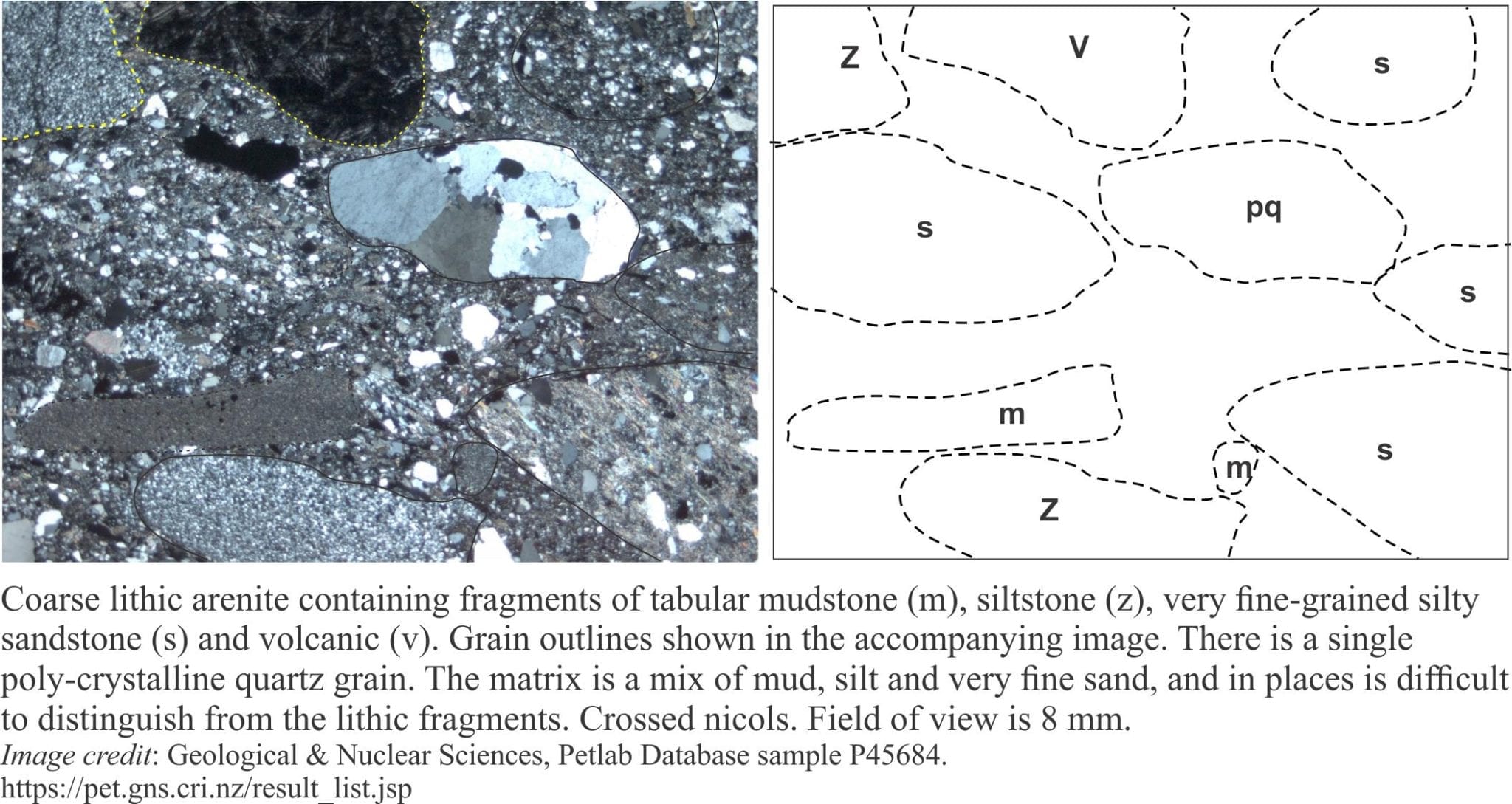

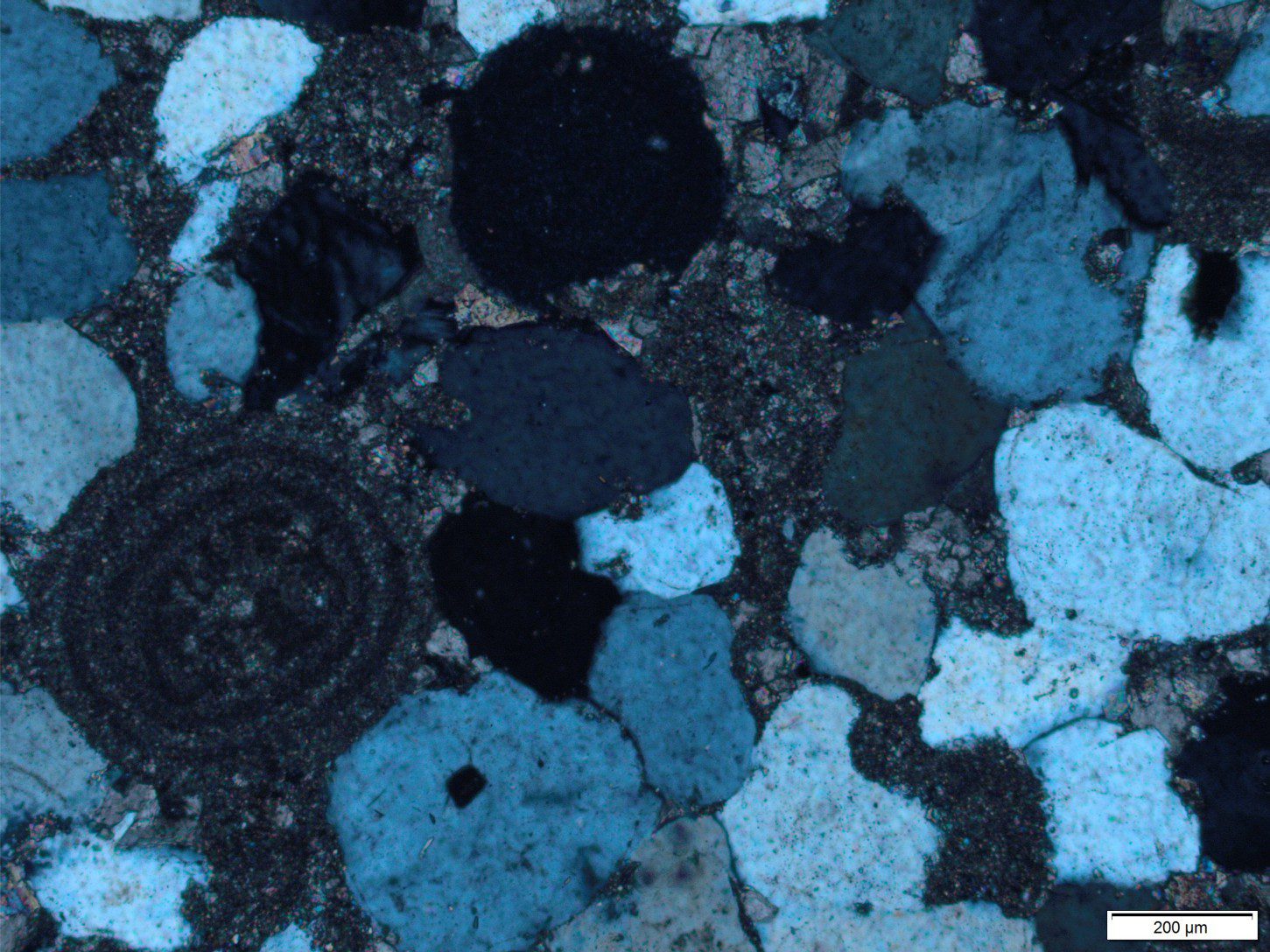

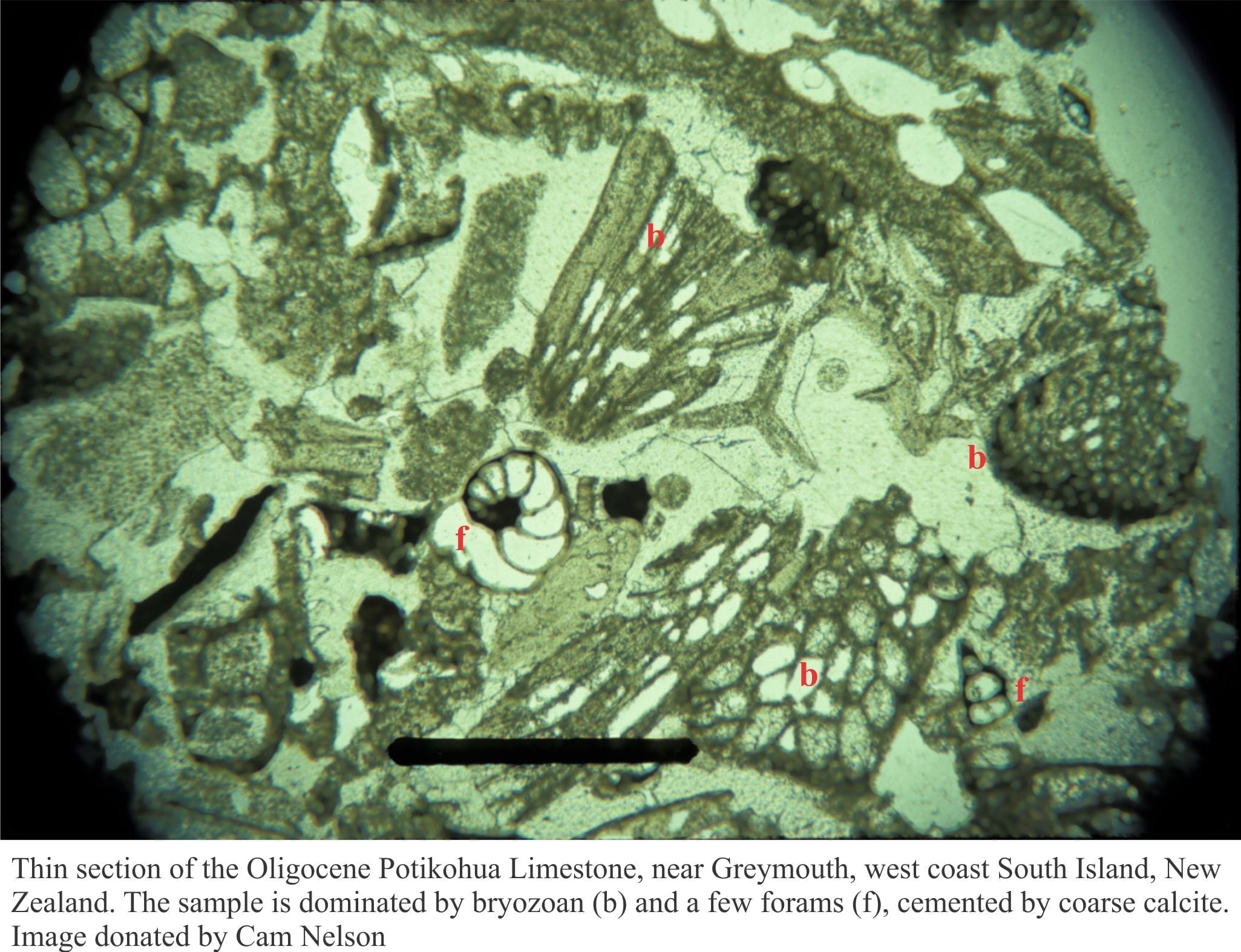

Sedimentary fragments: Sedimentary lithics are typically mudrock, siltstone, argillite and greywacke (keep in mind that mudstone is a mix of clay- and silt-sized particles). Fragments may be eroded from bedded siltstone or mudstone-shale, or from the matrix of coarse-grained lithologies; original bedding may be preserved in larger fragments. Distinguishing lithic grains from the matrix of the host rock is not always straight forward (see the example below). Some of the best thin section views of grain boundaries are in plain polarized light – under crossed nicols, grains and host matrix commonly merge into a dirty brown mass. These conditions are common in wackes where the proportion of matrix to framework is >15%.

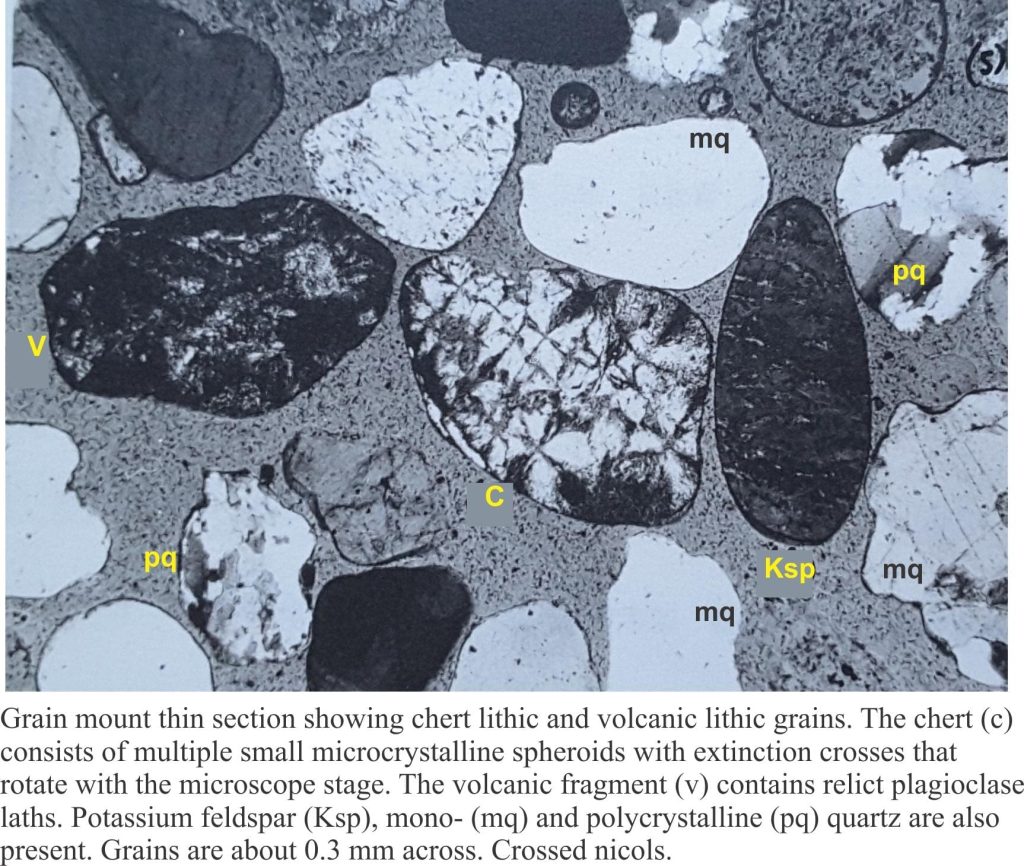

Detrital chert grains fall into this lithic category. Pure chert (micro- and cryptocrystalline quartz) can appear in many forms – as homogenous masses, as radial clusters (particularly in forms that precipitated in cavities), and as spherulites. Under crossed nicols, homogenous masses will have no uniform extinction patterns. However, fibrous varieties will commonly show sweeping extinction, whereas spherulitic clusters will display extinction crosses that rotate in concert with the microscope stage (see the example below). Chert can also include clay minerals that in some cases renders them indistinguishable from some mudstones.

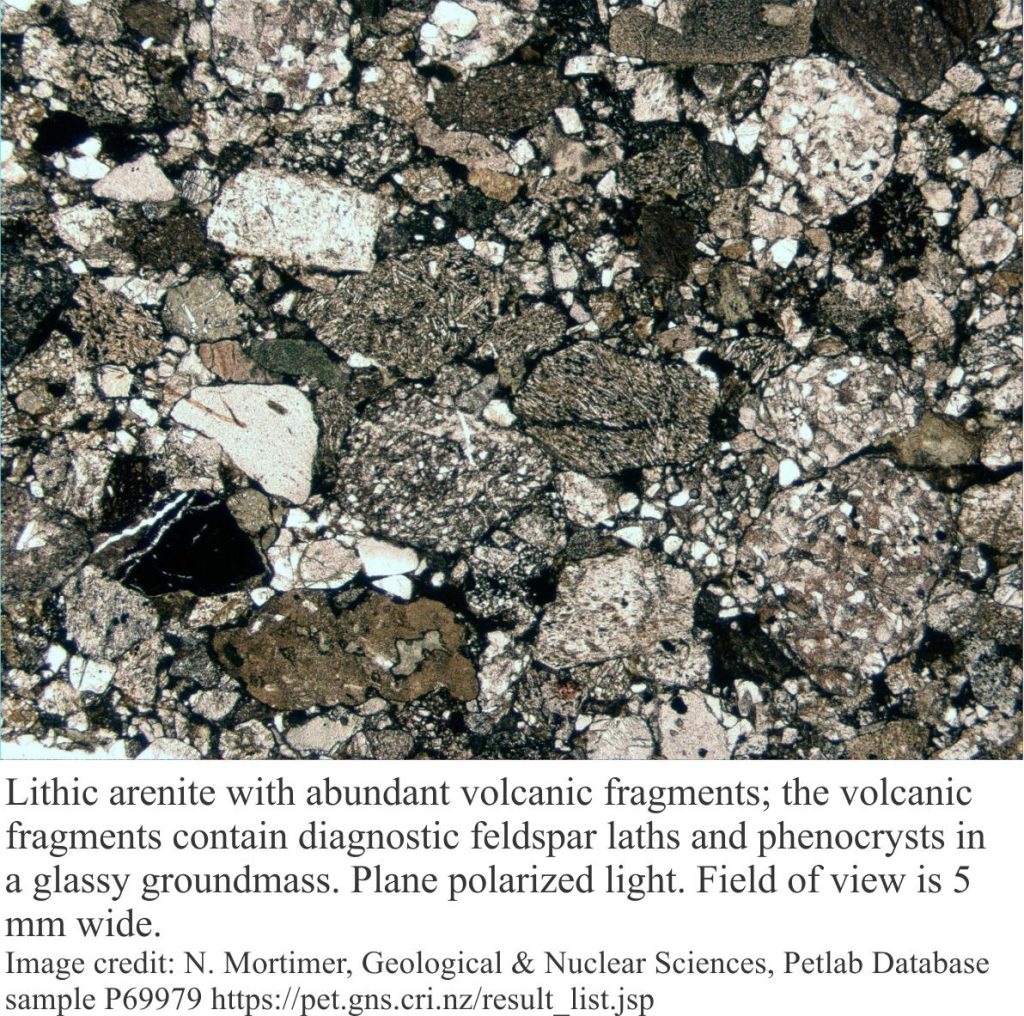

Volcanic fragments: Fragmentation of volcanic rocks releases phenocrysts and groundmass clasts to the depositional setting. The composition of groundmass varies with rock type but consists mostly of glass or its alteration products (commonly zeolites, clays and chert), and small crystals of feldspar, quartz, ferromagnesian minerals, and opaque minerals such as magnetite. The small crystals may be scattered randomly through the glassy groundmass or form felted masses – the latter is common in basalts as clusters of feldspar laths a few 10s of microns long; the laths may be aligned parallel to the original lava flow.

Metamorphic fragments: This category of source rock is most easily identified in fragments that show good alignment of minerals such as muscovite, biotite and chlorite – this applies to rocks with schistose foliation (schist, amphibolite). Fragments derived from lower metamorphic rank sources are more difficult to identify if there is no preferred alignment of minerals. Because most lithics in this category are fine grained, the microscope ID of metamorphic indicators like prehnite, or clay transformations from, for example, illite to muscovite, may not be distinguishable from other matrix constituents, requiring the use of additional methods such as X-ray diffraction.

Metamorphic lithic fragments can be distinguished from the host arenite matrix where inherited fabrics terminate at grain boundaries. It is important to distinguish these inherited grain fabrics from any post-depositional changes that affect the entire host rock.

Some useful links in this series

Lithic grains in thin section: Avoiding ambiguity

The mineralogy of sandstones: Quartz grains

The mineralogy of sandstones: Feldspar grains

Describing sedimentary rocks – some basics

Some useful texts:

Petrology of Sedimentary Rocks, Sam Boggs Jr. 2012

Clastic Diagenesis, D. A. McDonald and R. C. Surdam, eds., 1984. AAPG Memoir 37

AAPG Wiki– sandstones