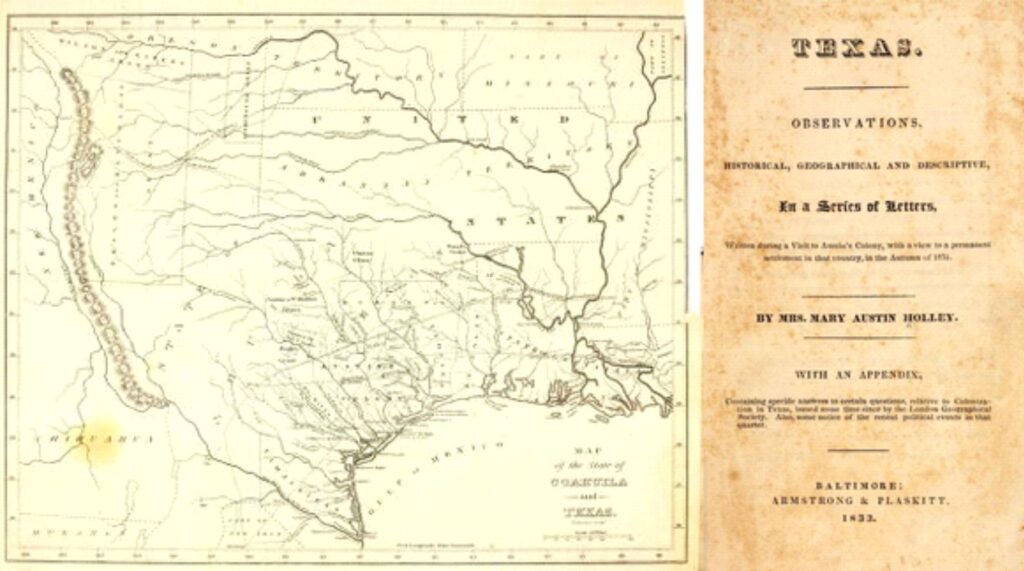

Mary Austin Holley was a prolific writer and artist. She is largely remembered for her cultural, historical, and geographic accounts of Texas, the first in written English and published in two collections of letters and diary entries: the first in 1833 Texas: Observations, Historical, Geographical, and Descriptive, and the second in 1836, simply titled Texas that included an account of the Texas War of Independence, the Texas Declaration of Independence, and Republic of Texas constitution (Curtis Dall, 1952; 2017).

Holley’s focus on Texas stemmed from familial ties to her cousin Stephen F. Austin who, following in his father’s footsteps, created Austin’s Colony. The land between Brazos and Colorado rivers was granted to Holley in 1821 by the Mexican government for the purpose of colonization and development of agricultural resources. It was the first American settlement outside the borders of the young US republic; it was also the most successful with more than 30,000 ‘immigrants’ (including slaves) by 1835 (the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 ceded land from the French covering most of the Mississippi drainage basin, about a third of modern contiguous USA). However, the increasing strictures of Mexican law, particularly those related to ownership of slaves, led to demands for independence that culminated in the Texas War of Independence, beginning October 2, 1835. Texas declared its independence on March 2, 1836, and this became cast in stone when Santa Anna’s Mexican army was defeated on April 21, 1836. Texas subsequently joined the Republic in 1845.

This then, was the backdrop to Mary Holley’s records of her travels to the Colony.

Mary’s Texas sojourns began about 4 years after her husband Horace Holley died (1827). Although she was not schooled in natural history (science), she is pictured as an astute observer of landforms, alluvial and fluvial processes, soils, and water supply. On the ephemeral nature of sand bars in Brazos River, she noted:

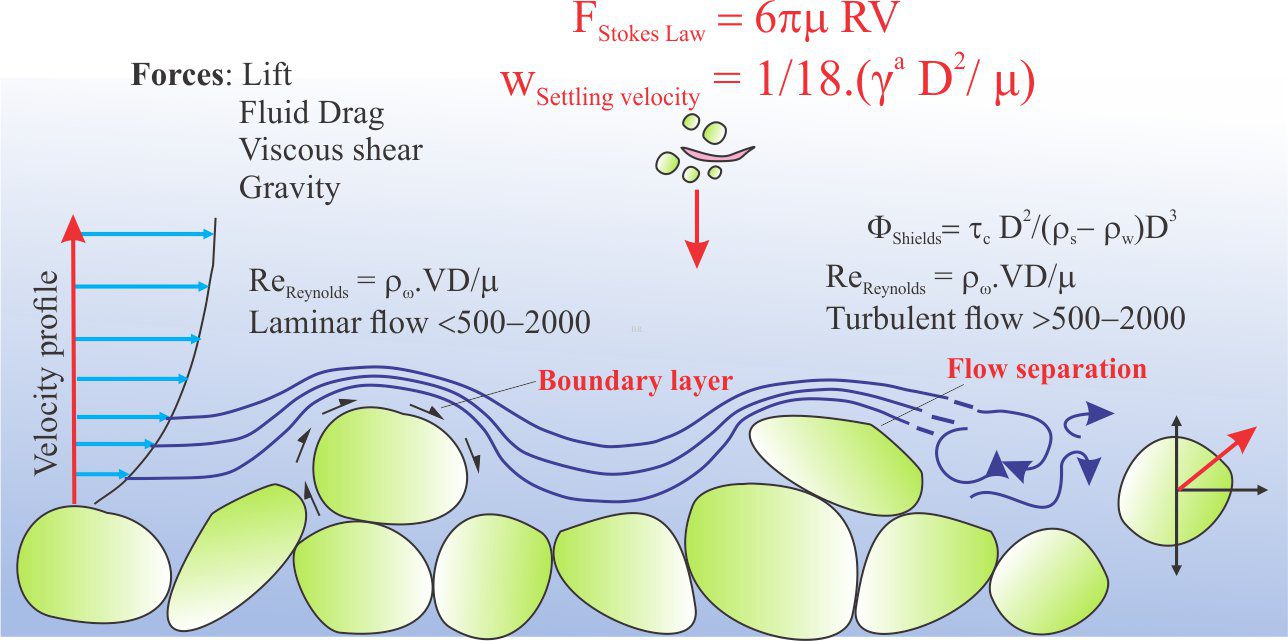

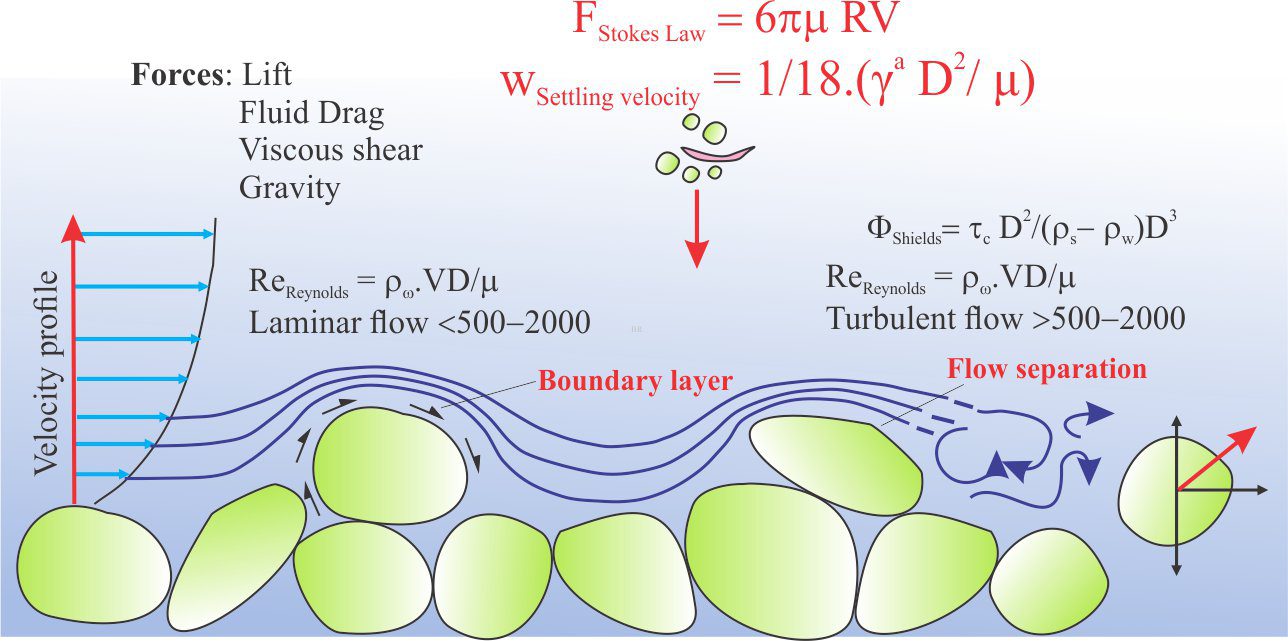

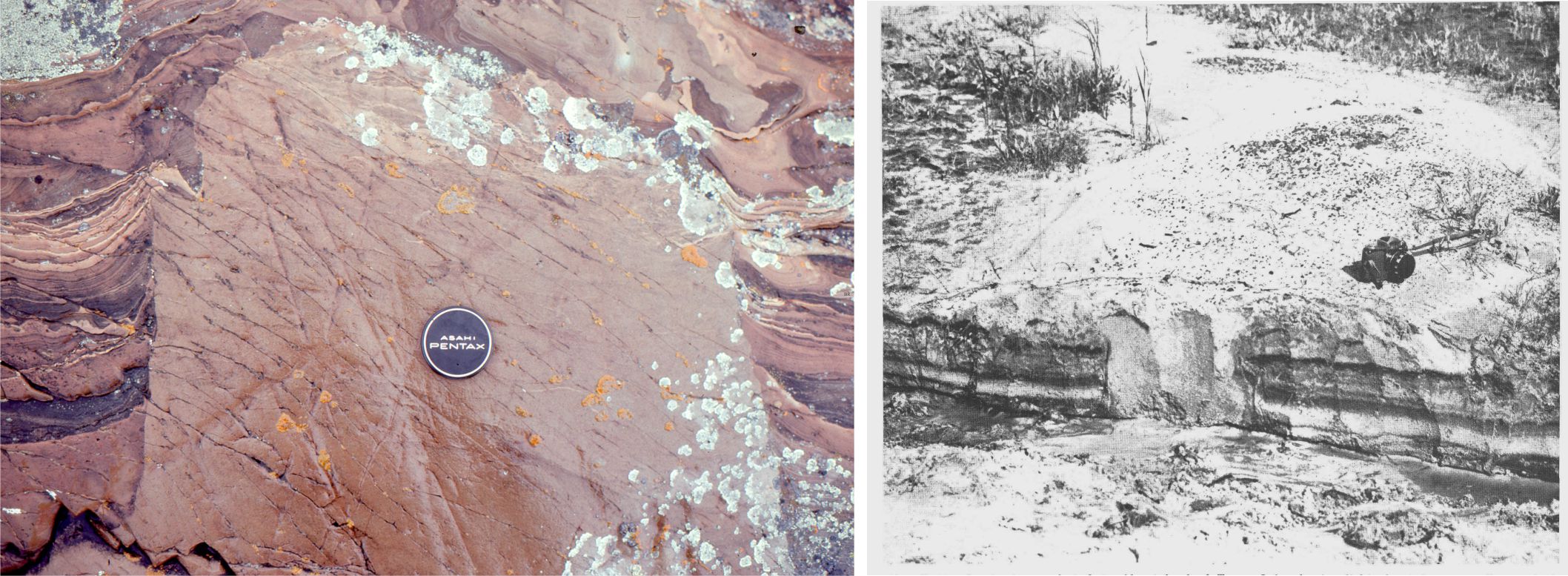

“This bar is not peculiar to the Brazos river. Bars are common to all the rivers of this coast. They are formed by the prevalence of the southerly winds, which act in a direction contrary to that of the stream, and by checking and dispersing the current, cause a deposit of the sand, which the water brings with it.” (from Texas: Observations…, p. 28-29). (Quotes from the Internet Archive link)

She then notes a “…very peculiar feature, in one of its branches, which has no parallel in any part of the world — a salt water river running from the interior towards the sea.” The salt content of Brazos River is derived from salt flats exposed along a tributary – Salt Fork of the Brazos River, about 90 km north of Abilene. In the next passage she describes the seasonal changes in river salinity (brackish) where “…a vast plain, of one or two hundred miles, in extent, the land of which, is charged with mineral salt, and on which nitre is deposited by the atmosphere. The rains dissolve this salt. When, in the dry season, the water is evaporated, the salt is deposited, in immense quantities, and the whole plain is covered with chrystalized salt. When, on the other hand the rains are copious, an extensive, shallow, temporary lake is formed, which discharges its briny water into the Brazos, by the Salt Branchy as it is called, its waters, being at times salt enough to pickle pork.”

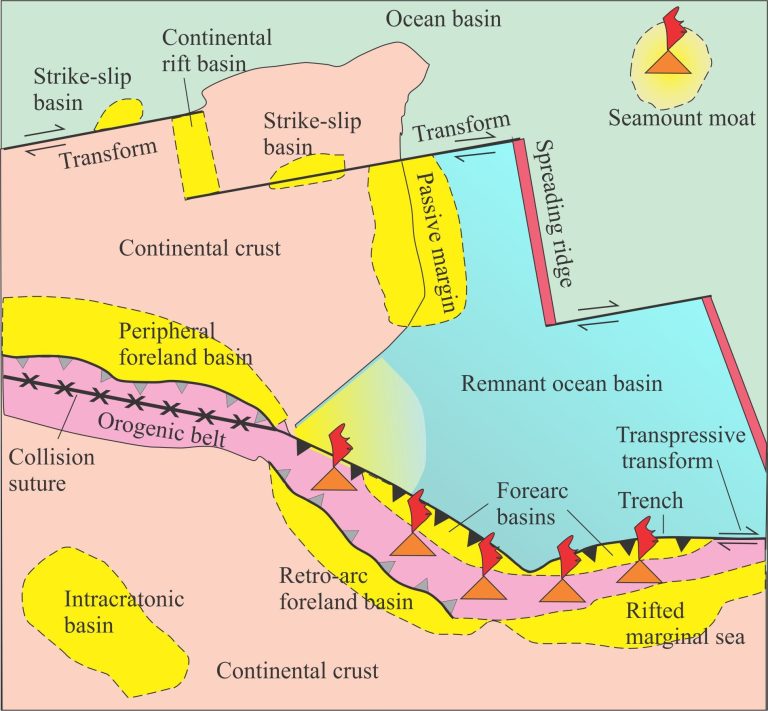

In her descriptions of Colorado River, she begins to delve into the geological past – “From these appearances, it is very evident that the Colorado, at some former period, divided at or near the present source of Caney and discharged its waters into the gulf by two distinct mouths more than twenty-five miles apart, forming an extensive island. This island constituted what is now called the Bay Prairie,…” (pages 57-58.).

Holley’s notes on soils are equally lucid where she surmises that soils developed on floodplains will have the compositional character of suspended sediment from rivers in flood. “The soil of the Brazos, Bernard, Caney, and Colorado lands, has the same general character, as to appearance, fertility, and natural productions. It is of a reddish cast, nearly resembling a chocolate colour, and is evidently alluvial, formed by deposits of the rivers during freshets. The colour of the soil is precisely such as would be expected from the appearance of the river at such seasons: for the Brazos and Colorado, when swollen by the spring and autumn freshets, are of a deep red and very turbid” (page 59).

She also comments on the relative stability of channel margins comparing those underlain by cohesive mud to unconsolidated sand, and the migration of active channels across floodplains underlain by muddy or sandy soils. “The beds of these rivers are deep and narrow. Their banks are clayey and not so liable to wear away as sandy banks, nor easily permit a change of channel.”

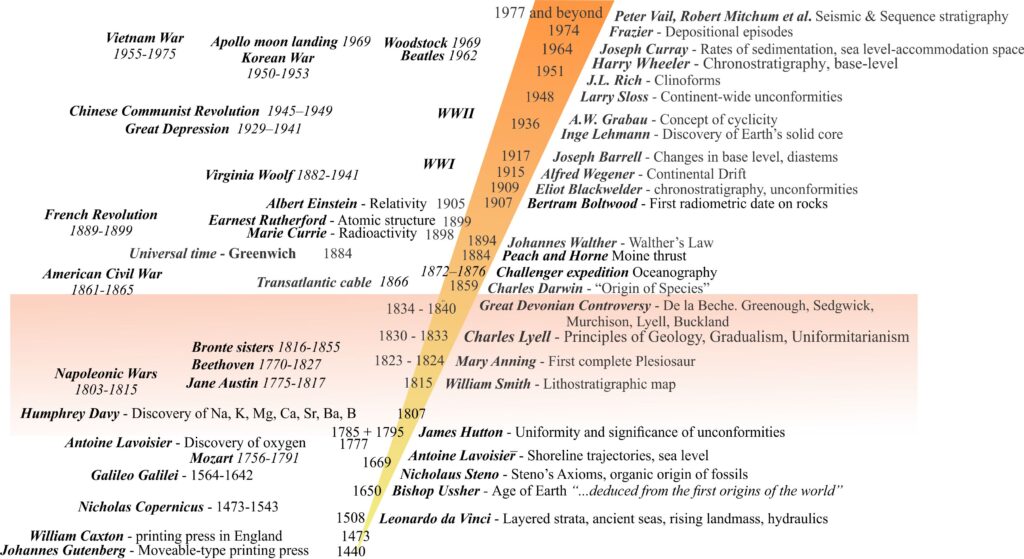

Mary Holley was born and schooled in New Haven, Connecticut. At the time there were no higher education opportunities for women, even with nearby Yale University that had opened its doors to men in 1701. The first college in the USA to admit women was Oberlin College, Ohio, in 1837; the first in Texas was Baylor University, chartered in 1845 and co-educational until 1851, then in 1866 the female department at Baylor received its own charter (R. Dulock, 2024). Her writings portray a keenness of observation and deduction, and a willingness to listen to others who had plied the rivers, tilled the fields, and drawn waters. They may seem a bit simplistic, but keep in mind that in 1831, for context, James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth had appeared only 35 years earlier (was it even available to her?); Charles Lyell had only just published the first volume of his Principles of Geology, and Henry Clifton Sorby, one of the progenitors of modern sedimentology, was only 5 years old.

The Appendix to the 1833 publication

In this section of her first book, she answers questions posed by the London Geographical Society, concerning (among other things) the nature of the soils, the navigability of the harbour adjacent to Galveston, the quality and quantity of surface and well water. The Appendix also contains copies of communications and opinions (including those relating local disgruntlement) from the principal actors of the Texas – Mexican political scene, among them Colonel Stephen Austin, and General Santa Anna of the Mexican army.

References and other links of interest

Mary Austin Holley, 1833. Texas: observations, historical, geographical and descriptive, in a series of letters, written 1831 and published 1833. From Internet Archive:

Mary Austin Holley: The Texas Diary, 1835-1838. 1965. Edited by James Perry Bryan, University of Texas Press.

Mattie Austin Hatcher, 1933. Letters of an Early American Traveler: Mary Austin Holley, Her Life and Her Works, 1874-1846. Southwest, Press, Dallas.

Elizabeth Reed, 1972. American Women in Science Before the Civil War. University of Minnesota, 1992.

Curtis B. Dall – 1952, 2017. Texas State Historical Association Holley, Mary Austin (1784–1846).

AUSTIN COUNTY HISTORY, Austin County Texas.

Briscoe Center for American History (The University of Texas at Austin).Mary Austin Holley Papers 1784-1846.

Rory Dulock, 2024. From separate universities to equal opportunities: The shared roots of Baylor, UMHB. Baylor Lariat.