Ora Hitchcock was an artist, often referred to as America’s first science illustrator, well regarded at the time, but largely forgotten more than a century later – until a couple of retrospectives reawakened interest in her talents: Orra White Hitchcock (1796-1863): An Amherst Woman of Art and Science (Herbert and D’Arienzo, 2011, Amherst College, Massachusetts), and 2018 at the American Folk Art Museum Charting the Divine Plan: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock (1796–1863). Both exhibitions presented her botanical, geological, and landscape works in the context of her life and beliefs.

Although her art is a fascinating glimpse into Orra’s persona and general knowledge of science, of equal interest are the reviews of the exhibition, that on the one hand give the impression of an egalitarian marriage borne of shared faith, respect, and mutual interests in the natural world, and on the other, reviews that dig a little deeper into the more disquieting aspects of Orra’s life in the context of 19th C social norms.

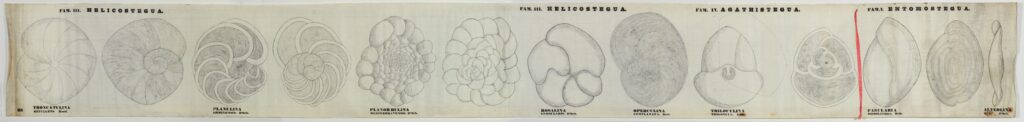

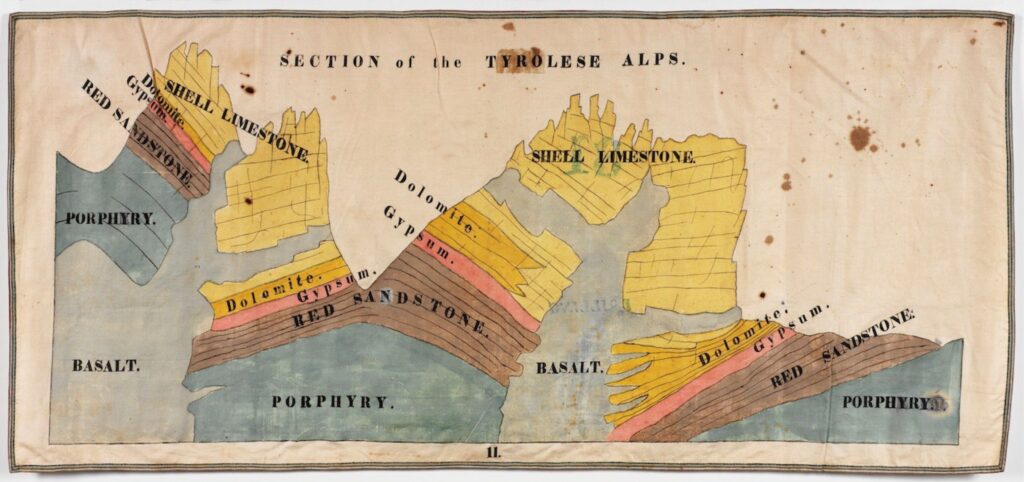

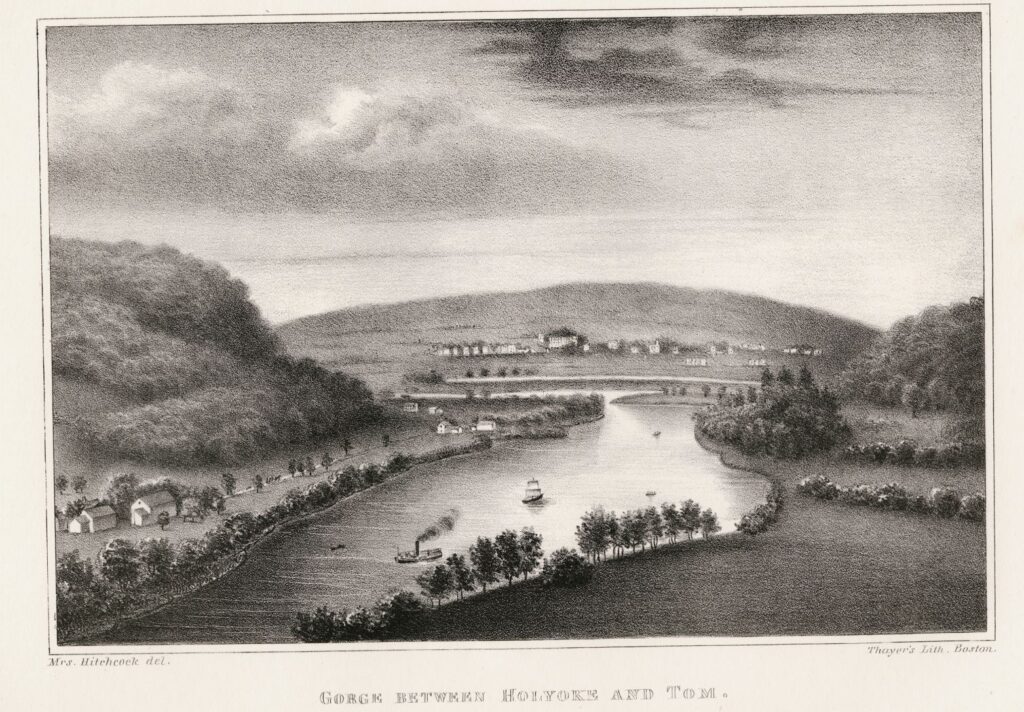

The primary recipient of her artistry was her husband Edward Hitchcock who she married in 1821. Edward was a geologist and teacher at Amherst College, eventually becoming its President. Orra created most of the diagrams and paintings he used in their joint and sole author publications and his classroom displays. Biographies note that her husband’s science publications and teaching materials benefited greatly from her illustrations, often done collaboratively, and that his work may not have proceeded as it did without her. He in fact was probably entirely dependent on her artistry – if she hadn’t done it, then he either would have had to find someone else or do without.

Orra Hitchcock was probably like many other women of that time, who wanted and occasionally succeeded in breaking free of the 19th C expectations of family life and dutiful partner in a fundamentally patriarchal society. In America, as in Britain and much of Europe, the legal existence of women ceased to exist when they were married and were regarded as the property of their husbands, although changes to these legal norms were certainly afoot in the USA before any substantial change in Britain (this did not change in the UK until 1928). Most scientific societies forbade them as members, and most universities did not permit enrollment in degree programs of any kind, let alone natural history programs. Many of those women (although not all) that did pursue science in some form usually did so as “assistants” or “companions” to their husbands. Hitchcock clearly had a passion for art and her alliance with Edward allowed her to pursue this in a manner that was socially acceptable. As the introduction of the Folk Art Museum’s exhibition stated, “Orra (w)as a woman who found a way to create visual works while complying with expectations of female modesty and affability of the early republic.”

The Hitchcocks were Calvinists. Much of what Orra painted and Edward wrote was imbued with the belief that science was not intrinsically evil, and that science and religious beliefs could exist side-by-side in an almost symbiotic relationship. What Orra painted was fundamentally an expression of God’s creation – hence the title of the American Folk Art Museum’s exhibition. A lengthy tome by Edward on the Final Report on the Geology of Massachusetts (1841) contains numerous references to He and Him. The report also contains landscape paintings created by Orra – her name Mrs Hitchcock appears on these, but I could find no mention or acknowledgement of her contributions in the text.

One of Edward’s best-known books – The Religion of Geology and Its Connected Sciences (1851) – is a clear manifestation of these beliefs, stated on the title page “Science has a foundation, and so has religion; let them unite their foundations,…”. And in this volume he acknowledges in glowing terms his wife’s contributions. “Both gratitude and affection prompt me to dedicate these lectures to you. To your kindness and self-denying labors I have been mainly indebted for the ability and leisure to give any successful attention to scientific pursuits…” (page iv).

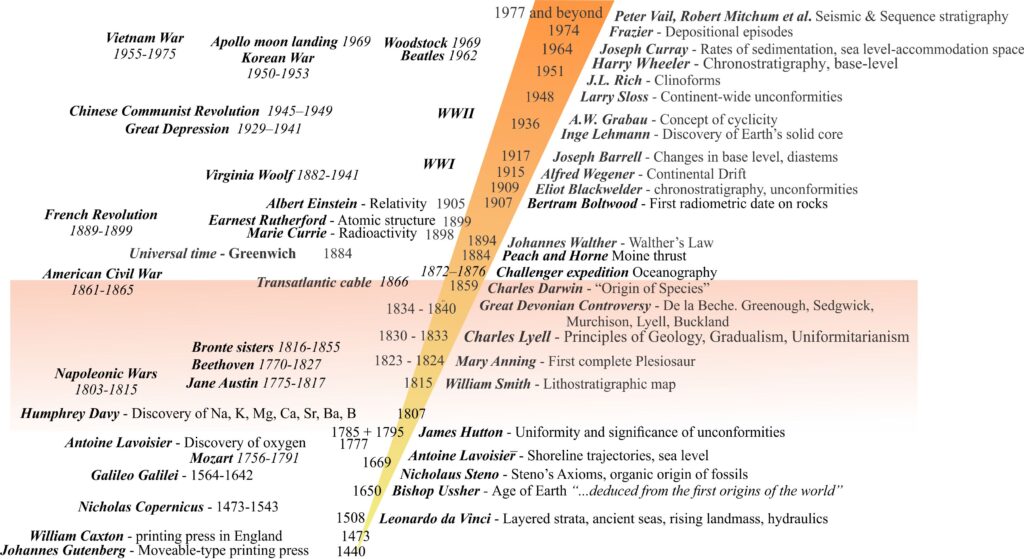

Despite this apparent symmetry between Calvinist beliefs and science, there was also disquiet at the direction science had taken when Darwin published Origins in 1859. Edward B. Davis, (2020) notes that the Hitchcocks favoured the Genesis version of creation, although not the literal version – they were aware of the immensity of geological time. The pluralism of science certainly had its limits.

A review of the American Folk Art Museum exhibition by Amber Harper (2018) provides an interesting contrast to the apparent ideal kinship of science and religion espoused in Edward’s fulsome acknowledgement of Orra. Archival letters and writings, including poems, hint at a level of disquiet with her marriage and a degree of melancholy, perhaps at her own fate and that of other women in a society that demanded obedience, in all its forms. From a letter to a newly-wed written in 1820, Harper paraphrases “that she check her hope of finding happiness in domestic life. Conceding that there are both “crosses” and “comfort” in marriage,…”. This sense of unease, perhaps borne of a puritan view of marriage, is also manifested in Orra’s collection of botanical drawings, where the reproductive organs in flowers (pistils and stamens) were sometimes omitted or brushed over – an attribute of her work that is at odds with the generally high degree of precision in her botanical portrayals. One example is of the Lady’s Slipper orchids in which the reproductive organs are prominent but which she de-emphasizes an otherwise delightful rendition.

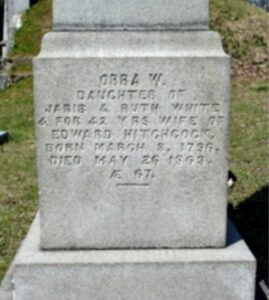

We can celebrate her artistry regardless of how we might envision her life unfolding. History, as we now know, had other ideas (the fate of most women scientists of this period) – Edward has been remembered and celebrated since the day he died, as is evident from the inscription on his tombstone: Born May 24, 1793 / Pastor at Conway / President and Prof. at Amherst College / A Leader in Science, / A Lover of Men, / A Friend of God: / Ever Illustrating / the Cross in Nature / and Nature in the Cross / Died Feb. 27, 1864. Orra’s epitaph notes only that she was wife of Edward and daughter of Jarib and Ruth White – with not even a hint of a reference to “ever illustrating”.

References and other articles or reviews

Orra Hitchcock, Herbarium Parvum, Pictum, 1817–1821.

Edward Hitchcock, 1854. The Religion of Geology and its Connected Sciences. 8th Thousand. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, and Company (the 1st edition was 1851). (Available online)

Robert L Herbert, Daria D’Arienzo, 2011. Orra White Hitchcock: An Amherst Woman of Art and Science. An exhibition at Amherst College.

American Folk Art Museum Charting the Divine Plan: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock (1796–1863) June 12, 2018–October 14, 2018.

Amber Harper, 2018. review of Charting the Divine Plan: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock, American Folk Art Museum: The Art of Orra White Hitchcock (1796–1863). Panorama: The Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art.

Meilan Solly, 2018. Art, Science and Religion Blend in Exhibition Honoring Illustrator Orra White Hitchcock. Smithsonian Magazine, July 30, 2018. (a review of the American Folk Art Museum exhibition).

Jason Farago, July 26, 2018. The New York Times review, “Mushrooms, Magma and Love in a Time of Science” (paywalled)

Stacy Hollander, 2018. Art, science, and the Second Great Awakening. The Magazine Antiques, August 23.

Edward B. Davis, 2020. The “religion of geology”. Christian History Institute , Issue 134.

Amherst College Archives & Special Collections, Amherst, MA: Orra White Hitchcock Classroom Drawings.