This biography is part of the series Pioneering women in Earth Sciences – the link will take you to the main page.

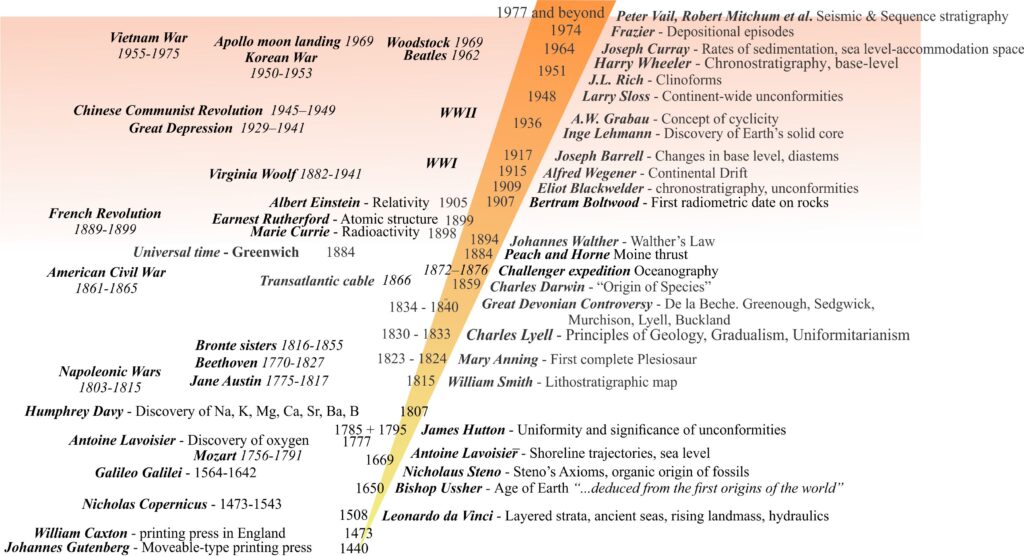

Ingrid Christensen born in Norway.

Evaluating the historical role that women played in emerging sciences is frequently plagued by a lack of written testimony, a problem that persisted well into the 20th century. Women might discover the first Ichthyosaur (Mary Anning1823-24), the molecular structure of DNA (Rosalind Franklin, 1953), or the Mid-Atlantic rift system (Marie Tharpe, 1953), but recognition was commonly ignored or relegated to footnotes or condescending remarks about their cleverness. Unless diaries or correspondence were kept either by the women themselves or folk close to them, then historians are left guessing – were these pioneering women responsible for the ideas or interpretations, the collection, recording and analysis of data, the creative impulses that led to discovery, or were they just useful backdrops to the world dominated by the other 50%?

The historical precedent as to which woman was first to set foot on the Antarctic continent is beset with the same issues. Ingrid Christensen visited the continent four times (1931, 1933, 1933-34, 1936-37), sailing with her husband and shipping entrepreneur Lars Christensen. Attempts to land were made on the first here expeditions but all failed because of poor weather. In the meantime, Caroline Mikkelsen, a fellow Norwegian, had managed to step ashore during the 1935 voyage with her husband Klarius Mikkelsen who captained the whaling supply ship M/S Thorshavn. Thus, when Ingrid Christensen finally succeeded in stepping ashore at Scullin Monolith on Antarctica in 1937, the event caused few ripples because the honour had already been bestowed and hence little of the event is recorded.

[Scullin Monolith is a steep, rugged massif rising to 435 m bordering the East Antarctic shore, and underlain by granite and metasedimentary gneiss]

It seems that records of both women’s achievements are sketchy. There is no accurate record of Mikkelsen’s landing site and it wasn’t until 1995 that an Antarctic party found the rocky cairn and Norwegian flag on a small group of islands about 5 km from the mainland marking the landing site. According to Antarctic exploration lore and the vagaries of historical precedent, islands do not constitute part of the mainland and Ingrid Christensen is now credited with the accolade. Christensen was also the first woman to fly over the continent.

Women scientists would have to wait another 30 years before being ‘permitted’ to work in Antarctica, the usual excuses being that they were not suited to the physical rigours and psychological isolation, they would disrupt the camaraderie of the men, or that their presence would be a distraction to the men. Sadly, the latter reason turned out to be prophetic; in a 2022 survey the US National Science Foundation reported that 72% of female employees working on the continent had been subjected to sexual harassment or assault.

Neither Mikkelsen nor Christensen contributed directly to scientific discovery, but they did pave the way for future involvement of women on the continent. Simply staying alive on voyages like these was no mean feat. Both women have geographic landmarks named to recognize their achievements.

Geographic names

Ingrid Christensen Coast that the gazetteer defines as That portion of the coast of Antarctica lying between Jennings Promontory, in 7233E, and the western end of the West Ice Shelf in 8124E. https://data.aad.gov.au/aadc/gaz/display_name.cfm?gaz_id=126937

Mount Caroline Mikkelsen, elevation 235 m,between Hargreaves Glacier and Polar Times Glacier on Ingrid Christensen Coast.

References and other documents

Elizabeth Chipman, 1986. Women on the ice: A history of women in the far south. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 1986.

Jesse Blackadder, 2015.Frozen voices: Women, silence and Antarctica. Australian National University.

Kate S. Zalzal, 2017. Benchmarks: February 5, 1931 and February 20, 1935: Antarctic firsts for women (EARTH Magazine suspended publication in April 2019).

IAATO – International Antarctic Association of Tourist Operators. 2024. Women’s History Month: Shining a Spotlight on Antarctica’s Female Firsts.

Norsk Polarhistorie. Ingrid Christensen. (In Norwegian but can be translated).