A description of the common skeletal elements of hard, stony corals

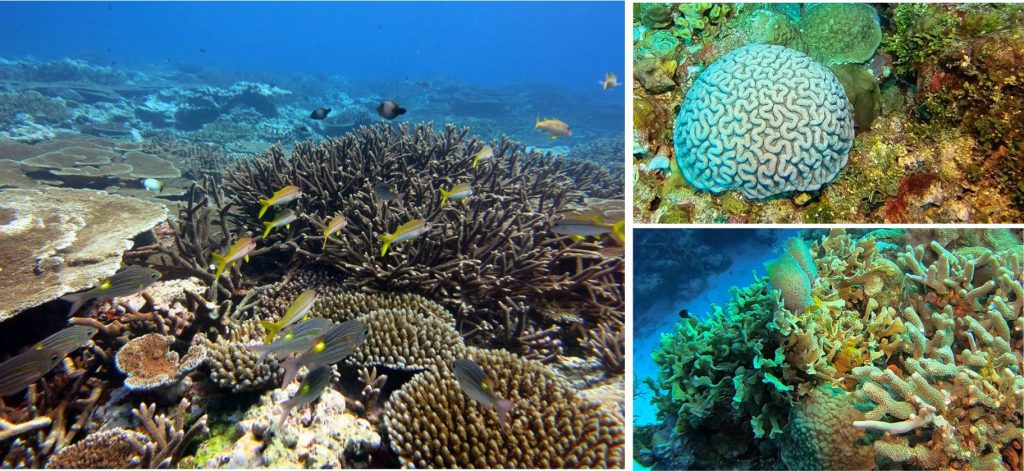

Hard corals are essential components of nearly all limestones. Colonial corals create the foundations for tropical reef associations (lagoon to deep forereef). They are also an important component of cool-temperate limestones, primarily as bioclasts of solitary corals.

Corals belong to the phylum Cnidaria, a group of animals that possess stinging cells, or nematocysts. The phylum includes hydrozoans like the siphonophores (Blue Bottles, Portuguese Man O War), true jellyfish and Sea Wasps (Box Jellyfish), a group of octocorals that includes soft corals, and the Subclass Hexacorallia that contains sea anemone taxa and the more familiar hard or stony Tabulate, Rugose, and Scleractinian corals. The latter three orders comprise the dominant species in the fossil record, as colonial reef-builders and solitary organisms. Modern reefs are dominated by the stony Scleractinians.

Modern Scleractinian corals, particularly the colonial reef-builders, depend for their survival on symbiotic, photosynthetic algae, or zooxanthellae. Thus, both algae and coral polyps thrive in water depths 30 m and less where solar energy in the photic zone is about 40% – 16% of incident light. Light intensity at these depths also depends on the amount of suspended sediment in the water.

Reef dwelling corals also do best in water temperatures at the high end of the 16o-32o C range, which generally restricts extensive reef development to the tropical latitudes. A few solitary and colonial Scleractinian species grow in colder waters, and at greater depths where the symbiotic algae do not rely on photosynthesis. Whether the extinct Rugose and Tabulate corals depended on this level of algal symbiosis is still debated.

All hard corals are marine. They are composed of calcium carbonate – Rugose and Tabulate corals of calcite, and nearly all scleractinian corals of aragonite although a small number of species have layered aragonite-calcite skeletons (Stolarski et al., 2020). Scleractinian corals are subject to recrystallization to low magnesium calcite during the early stages of diagenesis and burial.

Corals first appeared in the Early Cambrian but it wasn’t until the Ordovician that hard corals became major contributors to reefs (along with sponges, bryozoa, and other invertebrates), replacing the microbial stromatolite buildups that persisted through the entire Proterozoic. Tabulate corals appeared in the Early Ordovician, the Rugosa a bit later in the Mid-Ordovician. Both orders became extinct during the latest Permian mass die-off (along with many other invertebrates). The scleractinian corals first appeared in the Middle Triassic, rapidly becoming the dominant reef-builders we see today.

Skeletal morphology

The following skeletal structures are common to all or some of the three main hexacoral groups. Most of the external structures can be seen in hand specimens. Internal structures such as septa, tabulae, and dissepiments may be seen on broken or corroded specimens, on polished rock surfaces, or in thin section. Many of the photos were kindly provided by Annette Lokier, University of Derby.

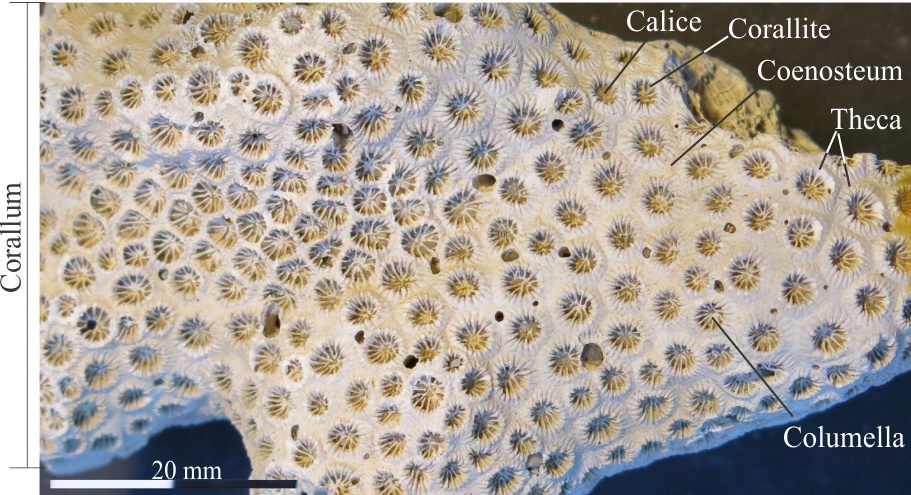

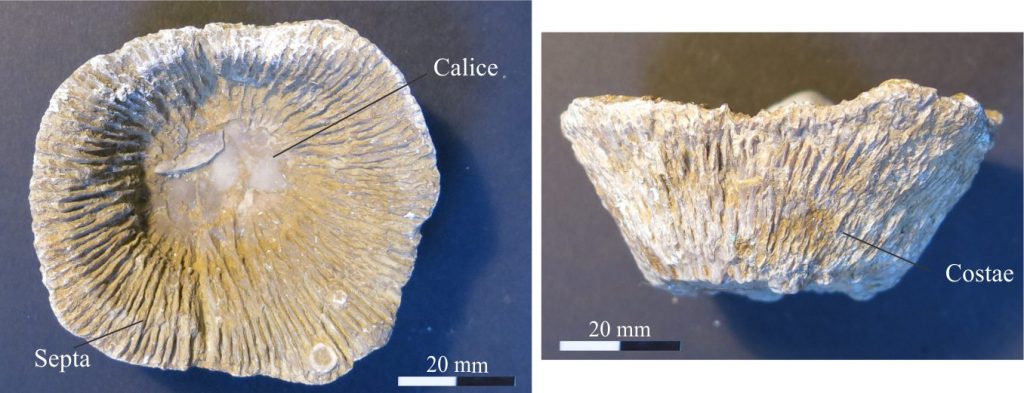

Calice, calyx: The uppermost cup- or chalice-like depression of a corallum or corallite that provides space for the living polyp. The base of a calice is commonly bound by a tabula and dissepiments.

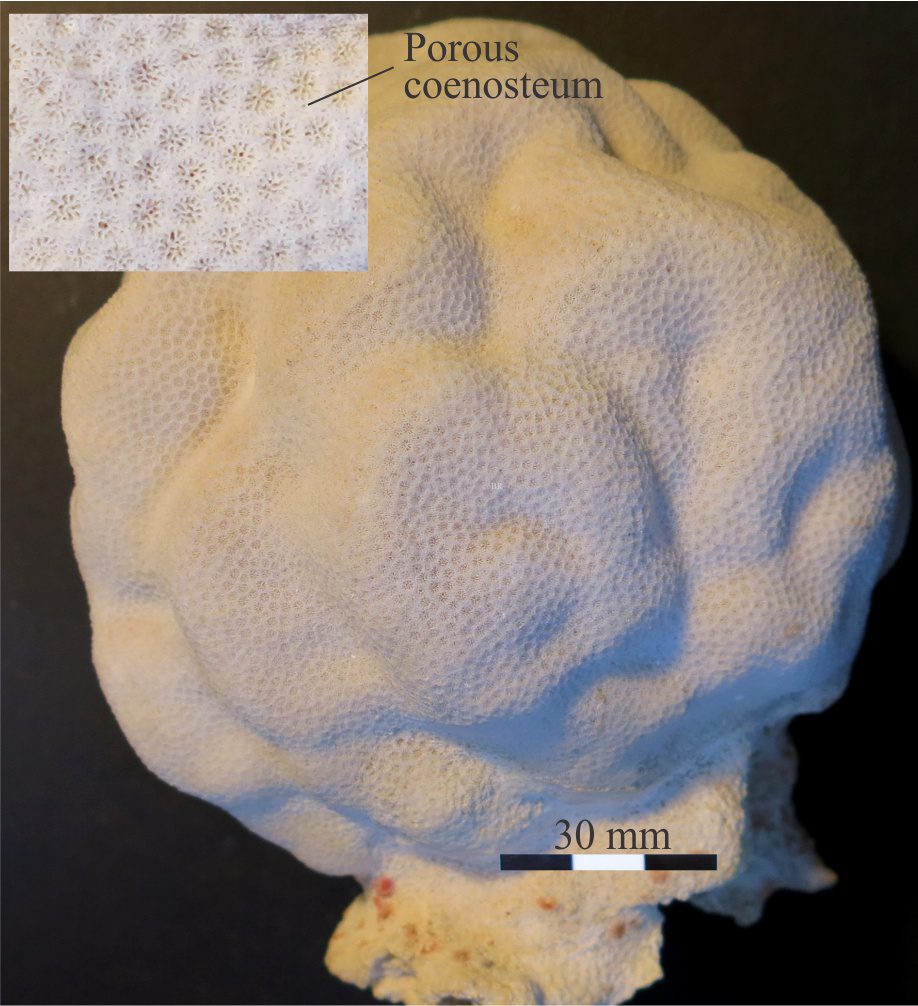

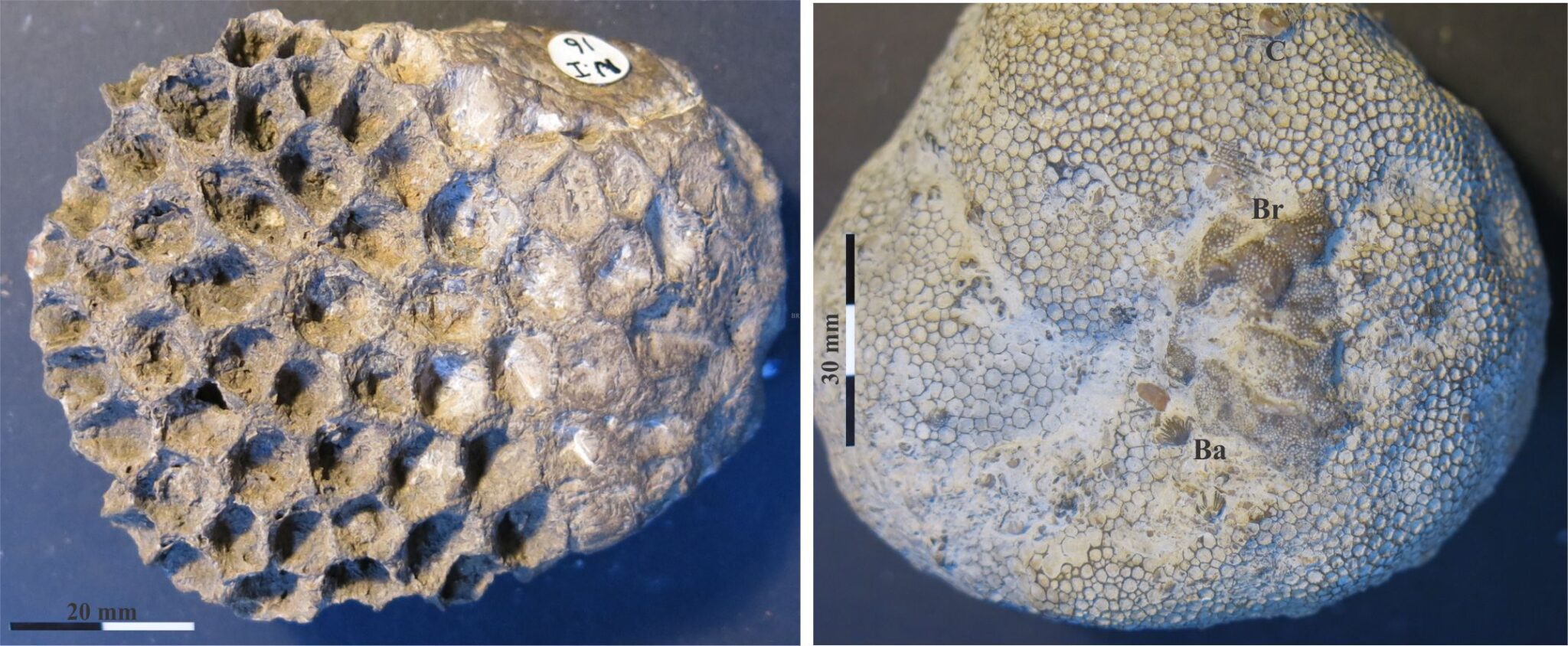

Coenosteum: (plural Coenostea) The porous calcareous structure that connects corallites in all three groups of colonial corals. It is part of the corallum in these colonies. In coenosteum-dominant species the corallites are spread out, connected by broad coenostea – the opposite applies to corallite-dominant species. The coenosteum structure is sponge-like and constructed of calcareous tubes, spines, the extensions of costae, and networks of small plates.

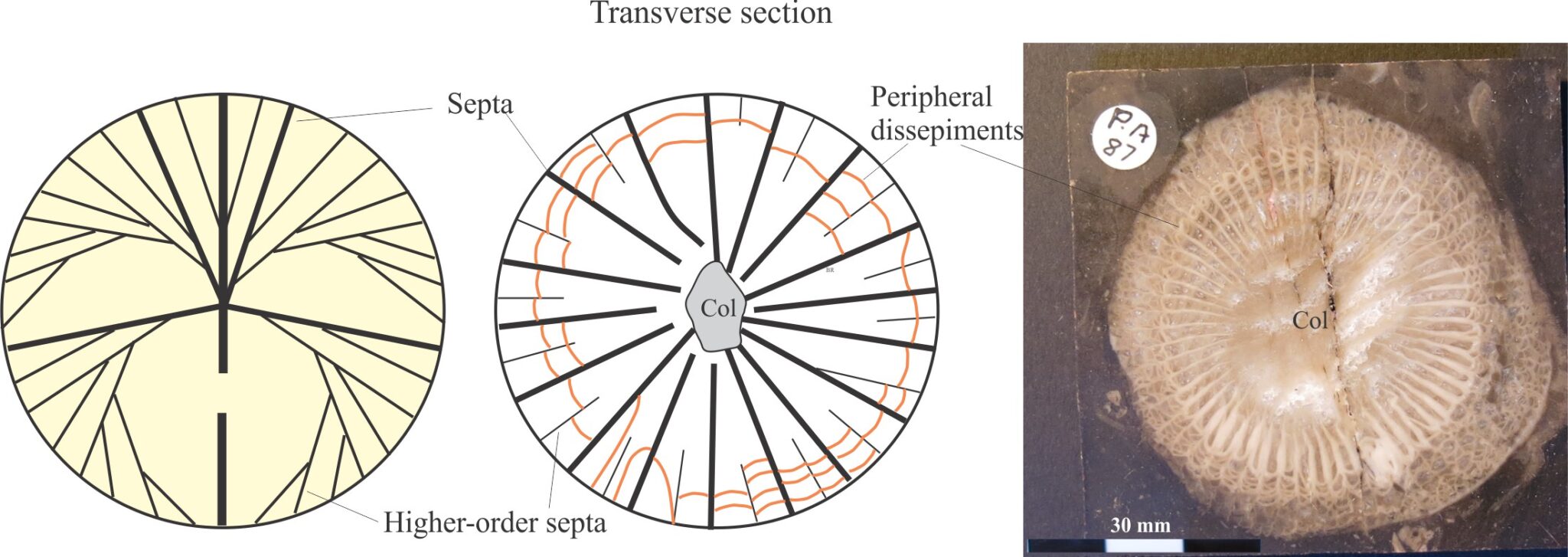

Columella: Present in Rugose and Scleractinian corals but not the Tabulates. In Rugose corals it is a central pillar-like structure from which the septa radiate towards the wall. In the Scleractinia, the columella, if present, is a mesh of tooth-like structures extending from the edge of the septa.

Corallum and corallite: There is potential for some confusion with these terms. Corallum (plural Coralla) refers to the whole skeletal structure of solitary corals (that are constructed by a single polyp). It is discoid, tube-, vase-, or cone-shaped. The term also applies to the entire structure of colonial corals – this makes sense if we consider the colony as a single community of polyps. Individual structures within a colony are called corallites and each corallite contains a single polyp.

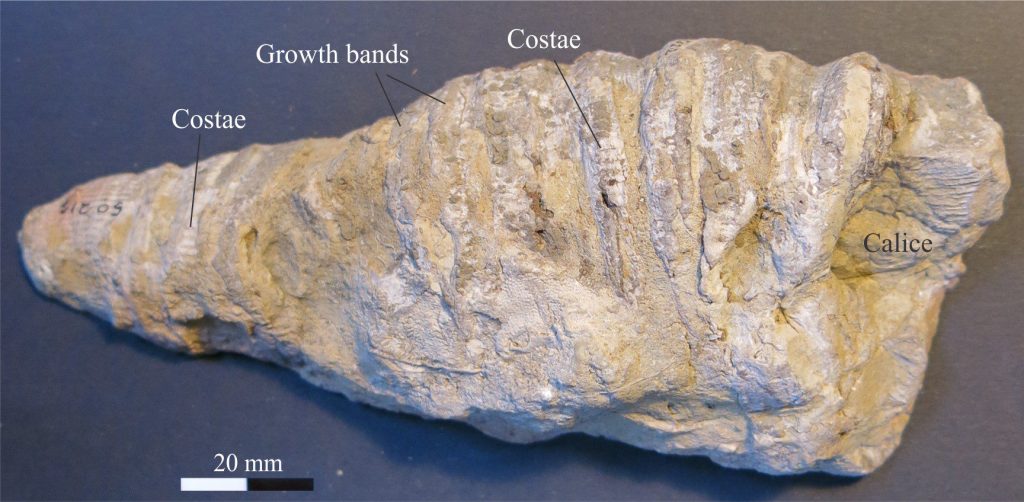

Costae: Rib-like structures aligned longitudinally along the epitheca of solitary corals; they are the extension of septa through the coral wall.

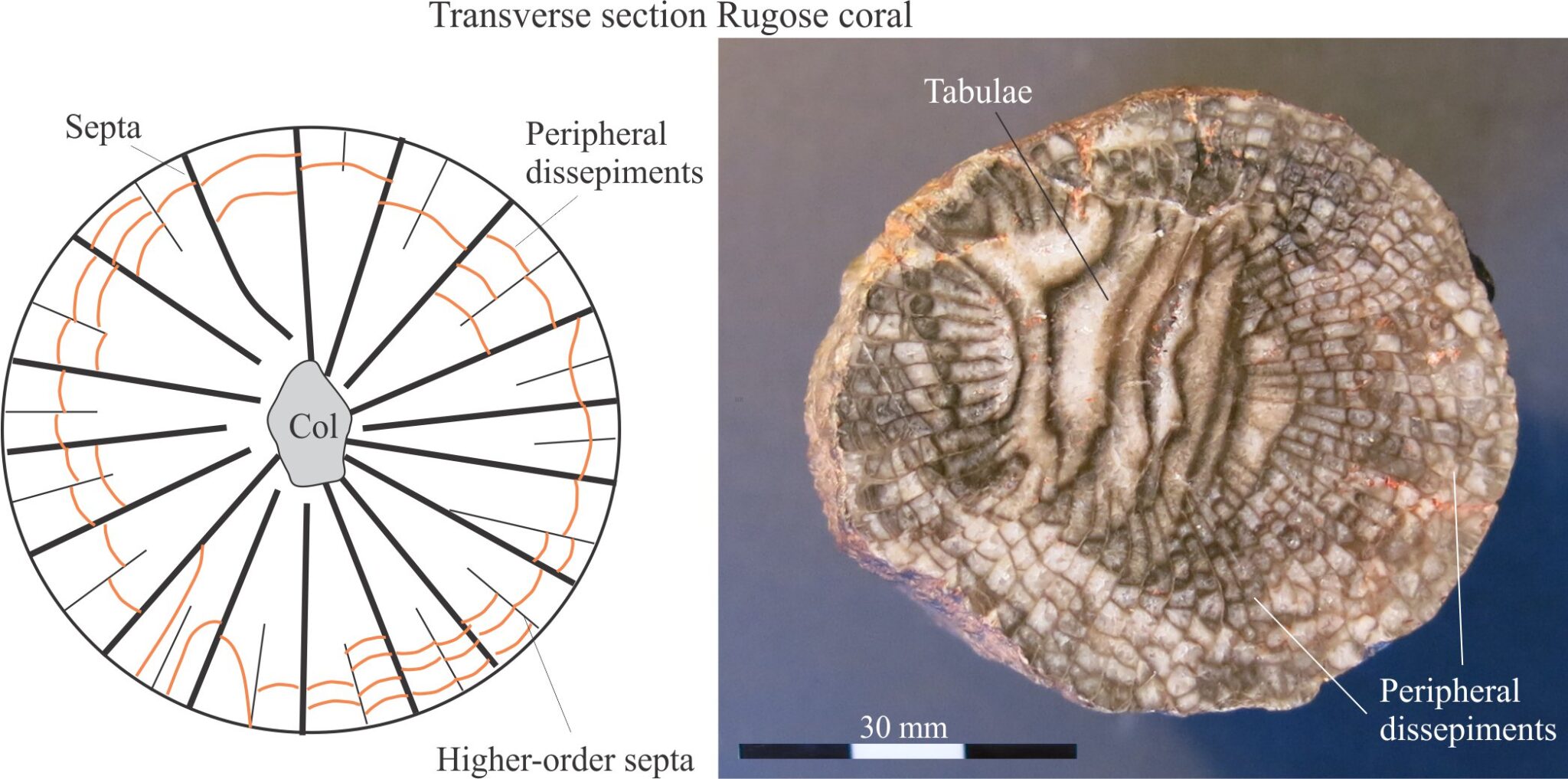

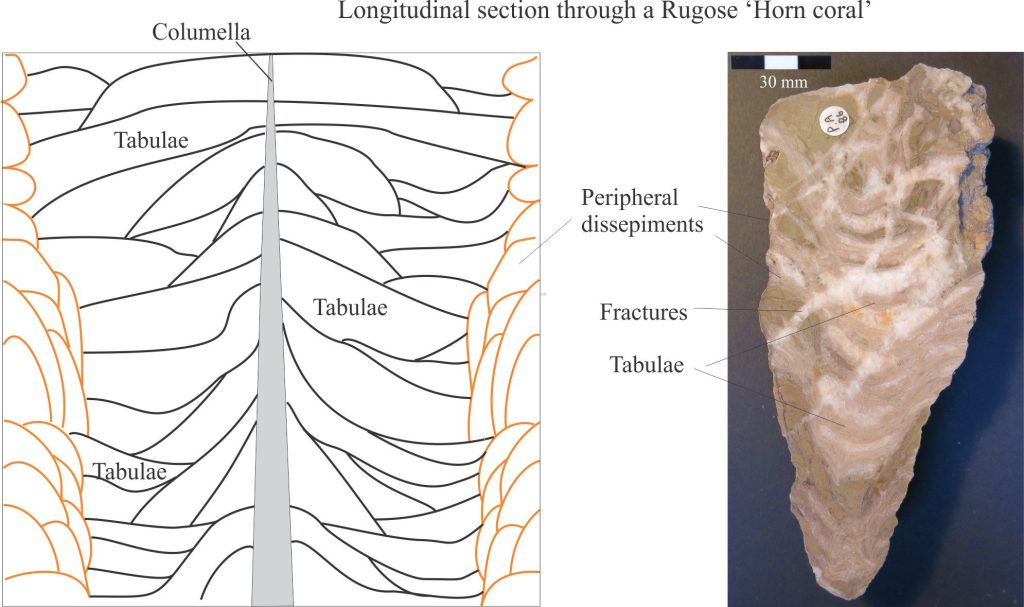

Dissepiments: Cup- or dome-shaped plates that grow between septa and separate the calice of a growing polyp from earlier growth stages. It has a similar function to the flatter tabulae. Both dissepiments and tabulae can occur together, with the former developed around the corallite periphery.

Epitheca: The thin, calcareous, outer wall of some solitary corals.

Fossula: (Plural Fossulae) Narrow gaps between the four quadrants of septa in Rugose corals; they are not always discernible, particularly if preservation is poor or there has been significant calcite recrystallization or neomorphism.

Growth lines: These are most prominent on solitary Rugose corals where they are expressed as raised concentric ridges on the epitheca. Their wrinkled appearance gave rise to the name of this order – from the Latin ruga. It is hypothesized that each line represents a day’s growth of the corallum. Statistical analysis has been used to estimate the lengths of solar years during the Paleozoic (e.g., Berkowski and Belka, 2008).

Horn corals: The common name for solitary Rugose corals having a horn-shaped corallum. They were the most common taxa of the Paleozoic Rugose order.

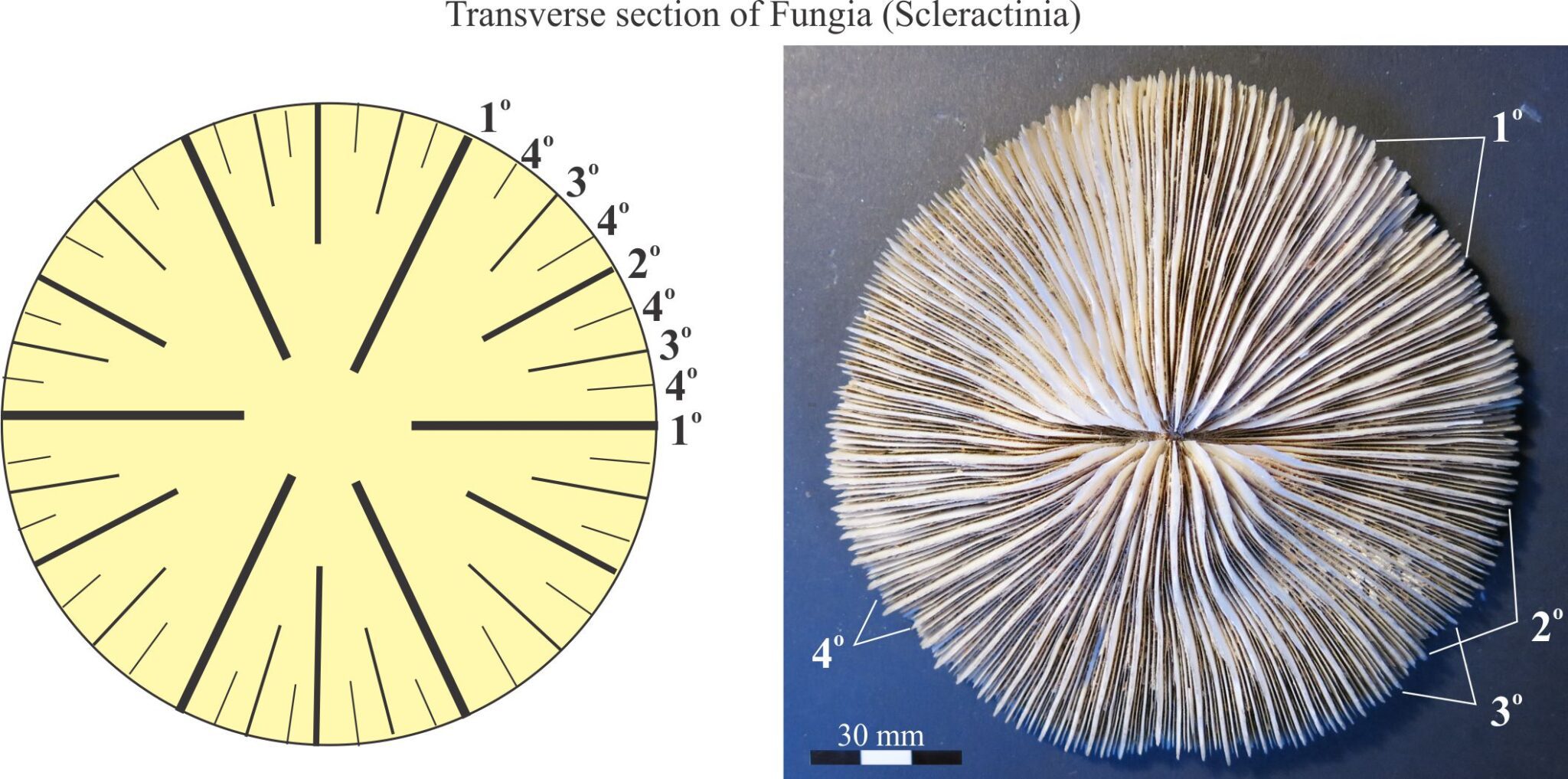

Septa: Vertical plates that radiate from the wall to the centre of a coral tube. They are secreted by the polyp as it grows from one calice to the next. In detail, septa may be laminated, perforated or spinose. Septa are prominent in Rugose and Scleractinian corals, but either absent or weakly developed in the Tabulates. In Scleractinian corals the septa are arranged in 6-fold symmetry, with primary septa the thickest and largest, and higher-order septa in sets of 12, 24 and so on in between. In Rugose corals the septa are arranged in quadrants separated by narrow gaps, or fossula; fossula are indistinct or poorly preserved in many species. The arrangement of septa in Rugose corals creates a bilateral symmetry.

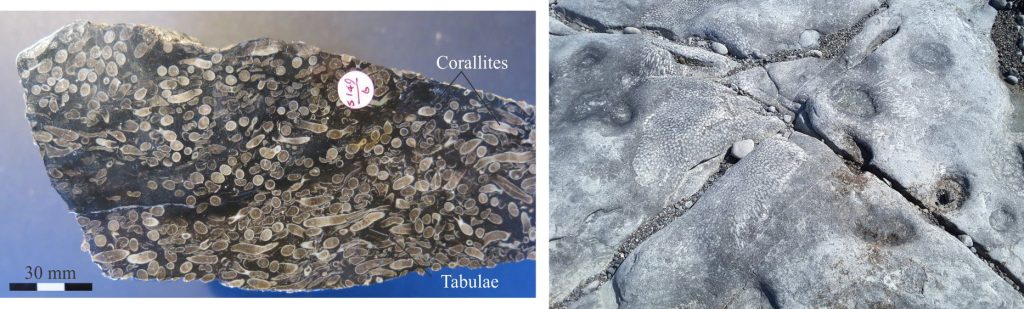

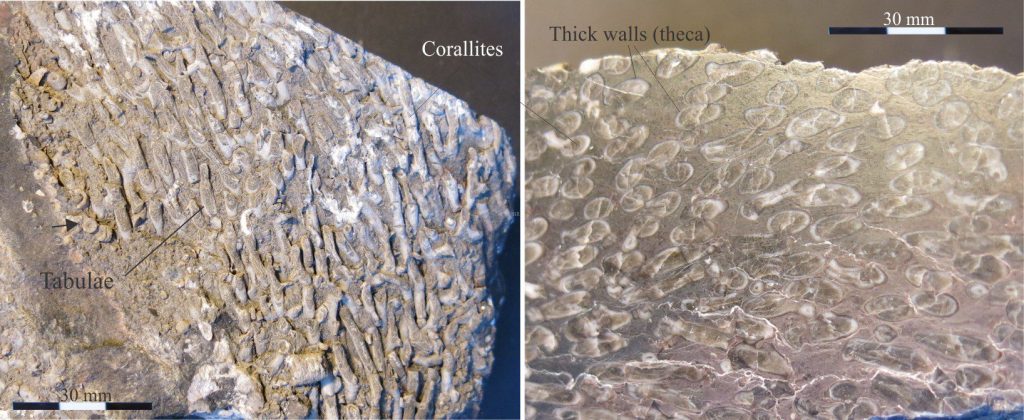

Tabulae: (singular tabula) Flat or slightly curved horizontal plates secreted within the corallite or corallum by the growing polyp as it moves to a new calice – the tabula separates the polyp from the rest of the coral tube. Present in Rugose and a defining characteristic of Tabulate corals; they are not found in the Scleractinians. Cf. Dissepiments.

Theca: The solid calcareous outer wall of a corallite or solitary corallum, thickened in some species and thin or compressed in others. The theca may be covered by an epitheca.

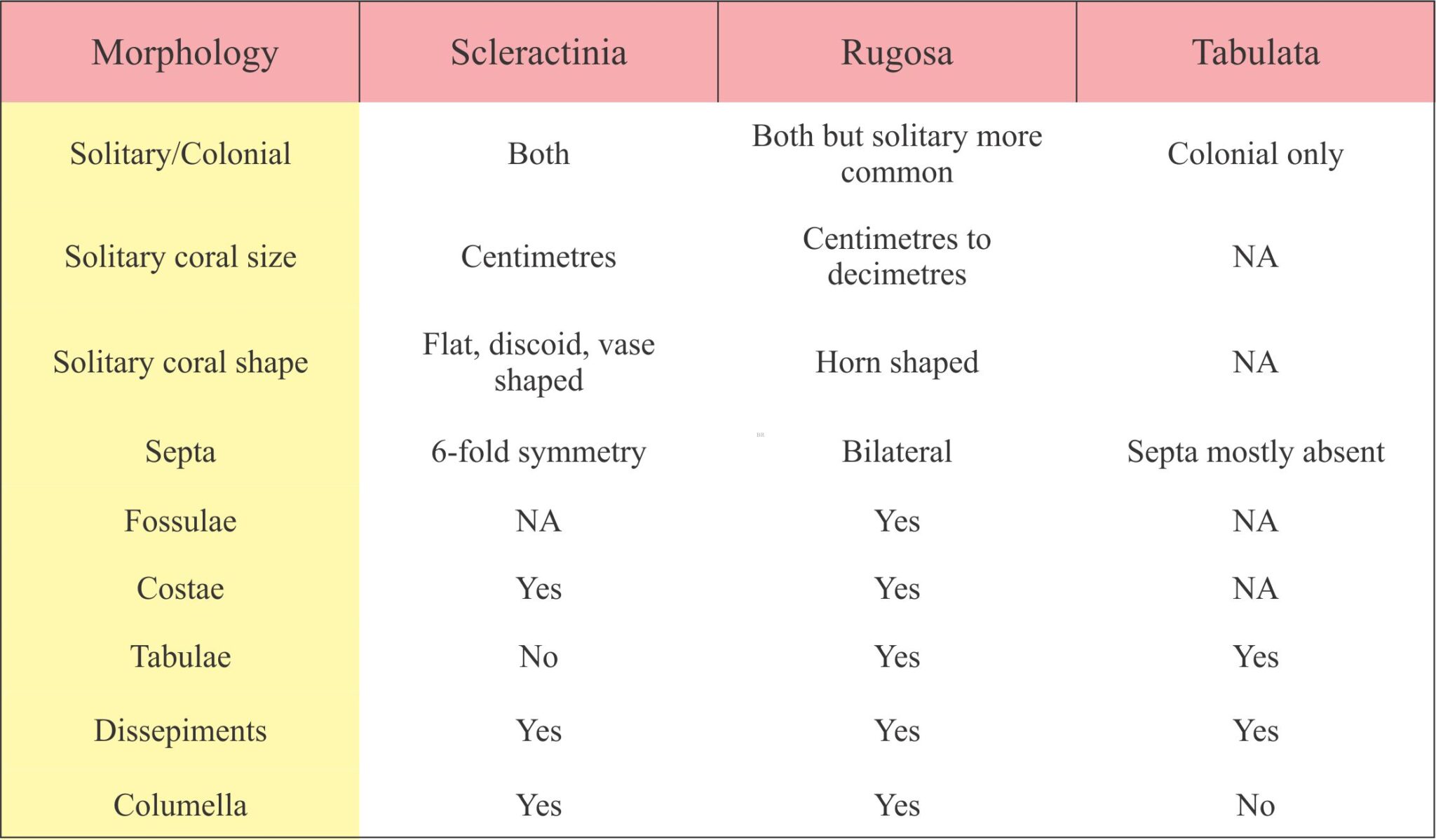

Distinguishing among Scleractinia, Rugose, and Tabulate corals

Distinguishing Rugose from Tabulate corals is reasonably straight forward based on the presence of septa. However, Rugose corals bear a superficial resemblance to the Scleractinians, particularly with their septa. One could argue that if a specimen came from post-Permian rocks then it must be Scleractinian – this is NOT a practice that should be encouraged (for any fossil group). Identification of the taxonomic status of fossils should be based on morphological criteria and not a presumption of age or stratigraphic context.

Scleractinia

The defining characteristic of Scleractinian, or stony corals is the 6-fold radial symmetry of their septa. The primary septa (6 or 12 of them; some species have 8 or 10 primary septa) are the largest and thickest plates that radiate from the centre of the calice, commonly from a columella. A succession of smaller, higher-order septa are inserted between these plates: 2nd, 3rd, and 4th order respectively.

Solitary Scleractinian corals have flat, dome-, discoid-, or vase-shaped coralla; the Fungia specimen shown above is discoid. Successive stages of polyp growth are separated by dissepiments. Colonial corals display an amazing variety of structures depending on species and environmental conditions such as wave and current energy. Common structures are branched, columnar, encrusting, foliaceous (leaf-like), laminar or table-like, and massive or bulbous corals. Some of these forms are illustrated below. Zooxanthellate colonial corals (i.e., those requiring symbiotic, photosynthetic algae) are the primary reef builders in post-Permian strata.

Rugosa

This extinct order is generally known for its horn-shaped solitary coralla (hence the name ‘Horn coral’), although colonial forms were also important as Paleozoic reef-builders. The overall length of solitary forms ranged from a few centimetres to one metre. The Rugosa also grew septa that, depending on the degree of preservation, can appear very similar to the Scleractinia. However, Rugose septa are arranged in quadrants that impart bilateral symmetry. In many species, each quadrant is separated by a longitudinal spacing, or fossulae, although these structures are not always easily discerned. Successive stages of polyp growth were separated by tabulae and dissepiments.

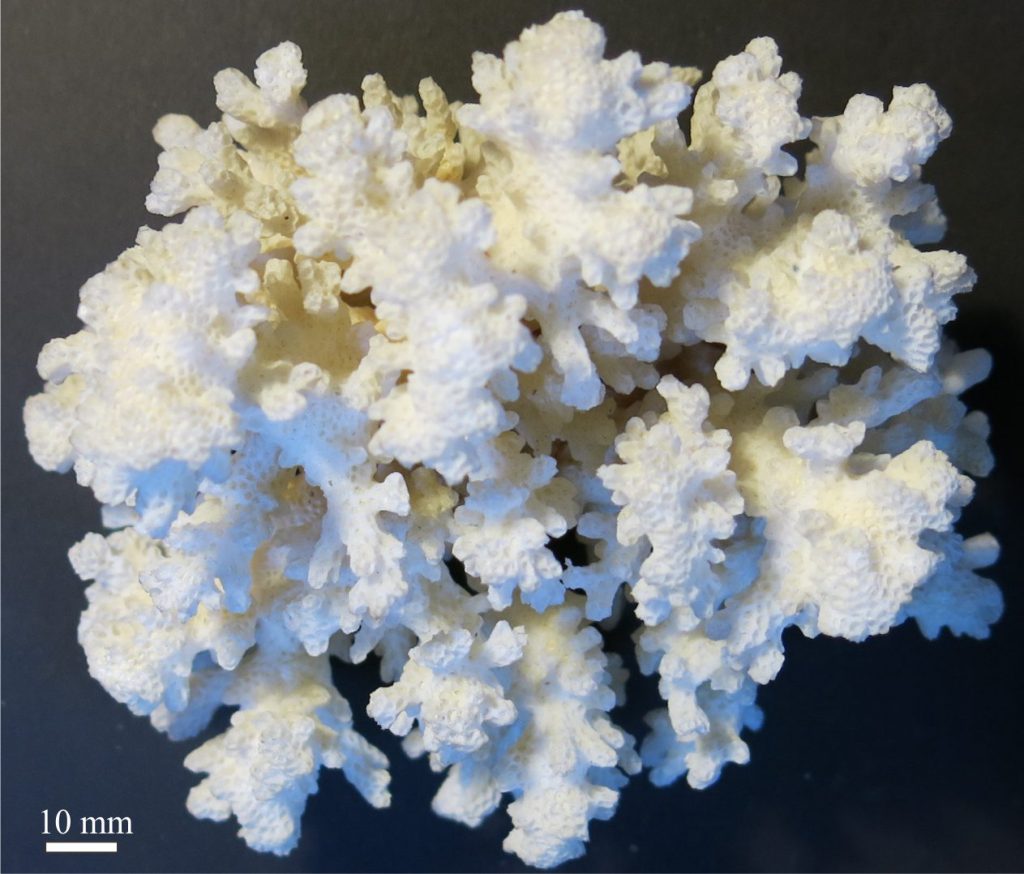

Tabulata

This extinct order is quite different from Rugose and Scleractinian corals. Tabulates only occurred as colonial forms. Except for a few species, their corallites had no septa. Successive stages of polyp growth were separated by tabulae (hence the name) and dissepiments. Growth of colonies was mostly encrusting although some species developed branching habits. Well-known growth forms include the honeycomb corals (e.g., Favosites), and three- dimensional chain-link structures (e.g., Halysites).

Other posts in this series

Bivalve morphology for sedimentologists

Trilobite morphology for sedimentologists

Gastropod shell morphology for sedimentologists

Cephalopod morphology for sedimentologists

Brachiopod morphology for sedimentologists